[ETA: I split this out of a book review of Abigail Shrier’s new book because the review was too long. I accidentally left in two very confusing paragraphs! Sorry everyone.]

Mental health advice on the Internet is often straightforwardly good: break down overwhelming tasks into smaller parts that aren’t overwhelming; be proud of doing things that are hard for you even if they wouldn’t be hard for other people; if beating yourself up didn’t work the past thousand times you tried it it isn’t going to work this time either. This advice makes people happier and more functional. For many people, it’s also much easier to access than, say, therapy or wise grandparents. Mental health communities on the Internet can save people’s lives.

But mental health communities on the Internet also give a lot of very bad advice. Some is idiosyncratic to the individual poster: no, sunning your balls doesn’t prevent depression. Others are common and characteristic of social media discourse about mental health. You might call it Internet Mental Health Culture.

Internet Mental Health Culture classifies as mental health conditions what is more accurately considered “the human condition.” Don’t like it when other people are invited to parties and you aren’t? This is called rejection sensitive dysphoria and it means you have ADHD! Like playing with fidget toys, and sometimes feel alienated in social situations? The former is stimming, the second is masking, and all that means you have autism! Procrastinate on boring tasks? That means that your body’s in a threat state, which is a response to trauma!

Man, trauma. Internet Mental Health Culture is particularly fond of “trauma.” In Internet Mental Health Culture, traumatizing events go far beyond the conventional life-threatening car accidents, religions which threaten you with Hell for doubting the Supreme Leader, and parents or romantic partners who hit you or are cruel to you. Being rejected by your friends is trauma. Having undiagnosed ADHD is trauma. Growing up trans or gay or a woman in a patriarchal society is trauma. Existing in a capitalist society is trauma. Climate change is trauma.

In many cases, in its fondness for trauma, Internet Mental Health Culture winds up expanding previously useful words to the point of meaninglessness. For example, “parentification” refers to a relatively uncommon form of trauma in which a child takes on an adult role: a twelve-year-old in a family with eleven children who is the primary caregiver of her six-month-old brother; a fifteen-year-old who financially supports the household because his mother is an unemployed alcoholic; an eight-year-old who monitors her heroin-addicted father for overdose, administers Narcan, and calls the ambulance. In Internet Mental Health Culture, however, “parentification” means a teenager cooking dinner three nights a week.

Of course, having undiagnosed ADHD or being a woman in a patriarchal society is unpleasant and can cause people to behave in a way that hurts themselves and other people. I will even, if pressed, admit the same thing about capitalism and climate change. But the question is whether it’s useful to put these experiences in the same category as life-threatening accidents and abusive parents. I really don’t think it is! Combat veterans and child sexual abuse survivors observably behave in similar ways. These similarities aren’t shared by everyone who ever experienced anything that sometimes causes human suffering and/or suboptimal behavior.

Only about 1 in 3 people get PTSD after a conventionally traumatizing event. After a conventionally traumatizing event, most people go through a few bad months but then return to normal, and post-traumatic growth is common. But in Internet Mental Health Culture, trauma inevitably screws you up for the rest of your life. Once you are officially traumatized (and everyone except maybe Bill Gates is), every personality flaw you possess can be traced back to your trauma.

Trauma has a lot of symptoms, in Internet Mental Health Culture. Many of the symptoms are Barnum statements. Do you sometimes feel disconnected from what’s going on around you? Do you struggle with trusting people? Do you have trouble feeling grateful for good things in your life? Do you try to get people to like you by bragging or by trying to appease them? Do you cope with stress by throwing yourself into your work or by doing things that comfort you, even if it’s a bad idea in the long run? Do you have migraines or insomnia or fatigue or back pain or random inexplicable nausea? To be sure, extreme versions of all these traits can be pathological. But mild physical health conditions, caring a lot about being liked, occasional dissociation, poor coping mechanisms for stress, and taking good things for granted are all a normal part of life for most people.

The problem is compounded by advice that is sometimes good for some people.

When I was on Tumblr, you occasionally saw viral posts like “if you didn’t brush your teeth today, you’re valid!” Some people legitimately struggle with personal hygiene. Our culture stigmatizes people who have difficulties with hygiene through no fault of their own. Many people with poor hygiene wind up in a pit of shame and self-hatred. Some people skip dental care because they’re so ashamed of what a poor job they’re doing brushing their teeth—which makes them more likely to have serious dental problems. For these people, destigmatizing failure to brush your teeth is helpful. Shame and self-hatred are unpleasant and don’t actually make you any more likely to clean your teeth.

On the other hand, lots of people could brush their teeth, but it’s annoying or they keep forgetting or they don’t want to get off their computers. For those people, posts like “if you didn’t brush your teeth today, you’re valid!” wind up normalizing poor oral hygiene. It feels like everyone skips tooth brushing. They don’t feel urgency about setting a reminder on their phones so they don’t forget; they don’t feel the little “unbrushed teeth are gross” impulse that gets people to get out of their nice warm beds. And then they have painful, expensive dental issues that could have been easily prevented.

On social media, it’s impossible to direct a message to and only to the people who need to hear it. And social media deals in soundbites and pithy quotes: the necessary two paragraphs of nuance get stripped down to a sentence attached to a cute image of smiling molars. This kind of thing is all over the place once you look.

“Cut off toxic people”: well, is the toxic person in question your husband who belittles your ambitions and has never picked up a sock in ten years of marriage, or is it your husband whom you have stupid fights with sometimes when you’re stressed and who can never remember your coworkers’ names?

“You don’t owe anyone anything”: well, are you constantly exhausted because you take on more commitments than you can handle, or are you refusing to comfort your sad friends because it puts you in a bad mood?

“Maybe you aren’t making excuses, you just can’t do the thing and that’s fine”: well, do you keep doing things that aggravate your chronic pain, or are you letting your wife support you because, if you’re honest with yourself, jobs are boring and video games are fun?

“It’s important to rest and take time for self-care”: well, are you taking regular breaks in order to make sure that you can carry out your duties sustainably, or is the thing you’re doing perhaps more accurately termed “self-isolation” and “numbing your feelings because you can’t bear to admit how miserable you are”?

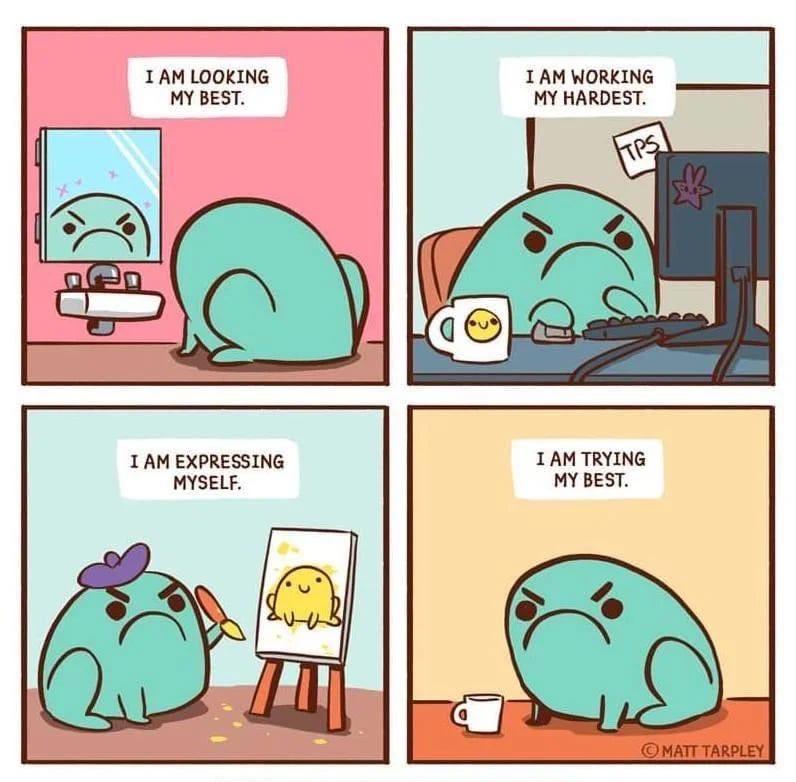

“Be kind to yourself”: does this mean using compassionate self-talk, or does this mean doing fewer things and making worse choices?

While literally every possible piece of advice is good for some people but not others, there is a pattern in which ideas Internet Mental Health Culture tends to talk about—one which I think is very harmful.

In its most pernicious form, Internet Mental Health Culture is about not being responsible. You always have a thousand excuses not to do anything.

People who have conflicts with you or need things from you are toxic. Cancelling your plans is self-care. Everything bad that happens to you is trauma, and in a just world you wouldn’t have to experience any of it. Productivity is a capitalist demand downstream of the Protestant work ethic, and lying in your bed watching Netflix is just as valuable as cooking dinner or picking up trash in a park. It’s not just that acquaintances make annoying suggestions like exercise for depression or planners for ADHD: it’s actually ableist to believe that you can take any steps to ameliorate your mental health problems in any way. You’re traumatized, you’re depressed, you’re autistic, you have ADHD: who can expect you to turn in your homework, do the dishes, tolerate mildly annoying people, or do what you said you were going to do? You shouldn’t have to make commitments, and shouldn’t have to carry them out if you’ve made them.

Of course, you can’t have the same expectations of everyone regardless of their personality and life situation. This isn’t just about neurodivergence: if someone has three children under five, the dishes are going to pile up and he’s going to flake on his plans. But, in general, as is appropriate for their circumstances, people should keep busy with things that matter to them, spend time with their friends, help others, try to cope when bad things happen, and make attempts to solve their ongoing life problems. If you don’t do that, you’re going to be depressed, because your life will be depressing.

In the worst parts of Internet Mental Health Culture, there are social rewards for misery. Sometimes, people will cut you endless slack if they believe that your bad behavior is because of your mental health conditions—but if you get better, all the support will suddenly disappear. Sometimes, being neurodivergent means you’re one of the good oppressed people rather than one of the bad oppressors. Sometimes, being a victim is a source of social power. Sometimes, being depressed means you’re socially aware: who wouldn’t be depressed in this environmentally devastated late capitalist hellscape? Sometimes, there’s just a vague sense that people like us are sad, and if you aren’t sad… well, maybe you don’t belong here at all.

Human are social animals. We’ll give up a lot for social approval: our goals, our ethical beliefs, our happiness, even our lives. There is nothing wrong with mentally ill people building community around mental illness, or for that matter with neurotypical people building community around self-improvement. But a community’s social norms should reward people, not punish them, for escaping misery.

I think I disagree about trauma - or, at least, I tentatively think I've benefited from the availability of the trauma lens in the kind of mental health posts I read, and from trying on that lens even though it didn't seem like an obvious fit.

Otoh I SO strongly agree with the stuff in the last paragraphs about incentives to be sad, especially when world events seem to point that way. I saw an extra strong version of that for most of 2022 among online anti-war Russians, where like, you were kind of supposed to signal that you're Not Okay because if you're somehow okay in these circumstances how can you be one of the good ones? but of course this comes up in US political/activist discourse as well. and like, fuck that, I intend to be okay even if the world is not, I can't wait for the world to be okay, that'll take too long

My experience of internet mental health culture is that it gives the part of me that wants to do less and quit faster a lot of tools to use to fight the part of me that wants to accomplish things, and so it causes me to accomplish less and thereby be more miserable. I think I'd be better off and happier and be better at doing things if I accomplished things, and as a result arguments that make the metaphorical devil on my shoulder better at whispering that I should quit make me worse off.

This is just one person, of course, and other people get the opposite result. Which is always the hard part of giving and receiving advice.