Trans Identity

David Halperin’s How To Be Gay is an insightful work of queer theory by the only queer theorist who understands how to write a coherent English sentence.

Gay identity is an interesting phenomenon, Halperin points out, because it’s almost contentless:

gay identity… is taken to be an elemental, primary term, a term with no component parts and no subjective dimensions, a term that has to be accepted at face value and admits of no further analysis. Gay people simply exist. Some people are gay. I have a gay identity. And that’s that. (You got a problem with that?)

Gay identity has no cause (other than something something biology something born this way). Gay people certainly have nothing in common with each other, other than the accident of the gender they’re attracted to. Even as gay identity reduces the gay experience to sexual attraction, it desexualizes it. An identity is a cold sterile thing, not the hot thrum of desire. Halperin analogizes “gay” to “husband”: a word technically defined by sexuality, but which drains away all the sex until it’s safe for polite company.

Ultimately, gay identity is a political statement: it marks someone as a member of a morally neutral category that suffers oppression. The purpose of gay identity politics is to keep straight people from asking awkward questions about what gay people do. Shhhhhh. Don't think about all the stuff that you think is gross about us. Think about how love is love. Isn't that nice? Love is love.

I make fun, but gay identity is genuinely important politically. A culture can be fluid; desire certainly is; but an activist group has to be clear on whom they are and aren’t organizing for. And—to be perfectly frank—many straight people, even quite tolerant straight people, want to throw up when they think too hard about what two men do together in bed. The success of gay politics comes substantially from allowing those people to dissociate their attitudes about gay people from their visceral disgust, so they can be their best selves.

Is all this making anyone else think of another politicized, nearly contentless word ending in “identity”?

Trans people, we’re told, have this mysterious thing called a “gender identity.” A gender identity tells people, in some deep wordless way, that they’re male or female or both or neither or something else entirely. Gender identity is almost entirely epiphenomenal, affecting nothing except maybe pronoun choice. We’re good feminists, after all. Men and women can have the same interests, tastes, personalities, and social roles—although uncautious people often imply that gender identity governs whether your wear lipstick and how interesting your haircut is, which rather gives up the game.

Halperin contrasts gay identity to gay desire. Desire is, of course, what makes a gay man gay: gay men want to have sex with men. But gay male desire goes far beyond the details of sexual object choice. Halperin writes:

Gay desire does not consist only in desire for sex with men. Or desire for masculinity. Or desire for positive images of gay men. Or desire for a gay male world. All of those desires might, conceivably, be referred to gay identity, to some aspect of what defines a gay man. But gay male desire actually comprises a kaleidoscopic range of queer longings—of wishes and sensations and pleasures and emotions—that exceed the bounds of any singular identity and extend beyond the specifics of gay male existence.

I can’t get into all the subtleties of Halperin’s argument about gay male desire here: it takes up (and deserves) an entire book. But it does make me think about trans desire.

Andrea Long Chu writes, in On Liking Women:

I doubt that any of us transition simply because we want to “be” women, in some abstract, academic way. I certainly didn’t. I transitioned for gossip and compliments, lipstick and mascara, for crying at the movies, for being someone’s girlfriend, for letting her pay the check or carry my bags, for the benevolent chauvinism of bank tellers and cable guys, for the telephonic intimacy of long-distance female friendship, for fixing my makeup in the bathroom flanked like Christ by a sinner on each side, for sex toys, for feeling hot, for getting hit on by butches, for that secret knowledge of which dykes to watch out for, for Daisy Dukes, bikini tops, and all the dresses, and, my god, for the breasts. But now you begin to see the problem with desire: we rarely want the things we should.

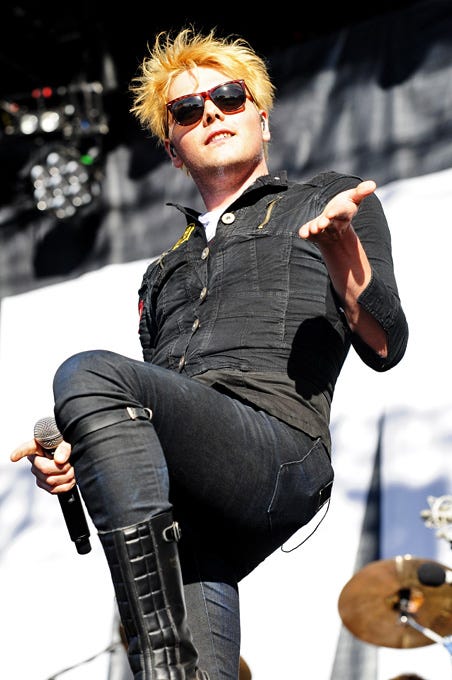

My story of trans desire is this: sometime in middle school, I conceived the desire to be Gerard Way, the flamboyant and fabulous lead singer of My Chemical Romance.

I obsessively learned everything I could about him. How he was in New York City on 9/11, which inspired him to quit his job at Cartoon Network and found My Chemical Romance to save teens from committing suicide. How he was a recovering alcoholic who faithfully followed the Twelve Steps. How he was married to Lyn-Z, the hot butch bassist of Mindless Self-Indulgence who did backbends on stage.

And I modeled myself on him. Numerous high-school fashion disasters came from one attempt or another to dress like Gerard Way. I spent two years playing guitar in spite of being almost entirely tone-deaf. I read Anne Rice and Grant Morrison and Alan Moore because Gerard Way recommended them, although not even he got me to like The Catcher in the Rye. The first time I played Magic: the Gathering, I felt an unutterable thrill: Gerard Way played Magic: the Gathering so it was the coolest thing ever.

In many ways, I’m not at all like Gerard Way. Soon after the thrill wore off, I realized that Magic is a colossally boring game. I shower regularly. I have heard of the concept of cause prioritization and attempt to apply it to my altruistic endeavors. While I am coparenting with someone named Lindsey, he has never once gotten a job as a bassist, despite not knowing how to play bass, because mid-audition he spat whiskey into the air and lit it on fire.

But, you know, I’m severely mentally ill and in recovery, taking it one day at a time. I write, and I try to make the world better through my writing. I play tabletop RPGs and read obscure science fiction. I have oddly colored hair and an awesome pleather jacket. And… I take testosterone, and now when people see me, most of the time they see a man.

It is politically inconvenient, to say these things. It opens you up to attack. “Men can wear dresses and lipstick, Andrea Long Chu! Men can cry at movies, men can use sex toys, a woman can pick up a man’s check. For God’s sake, a man can have female friends!” Do I think, perhaps, that women can’t be nerds or artists or rock stars? If I had had a Strong Female Role Model (TM) in middle school, would I have been cis? Is this, perhaps, all a very complex outworking of a sexual fetish?

It feels frivolous to transition because I want to look like the person I dreamed of being in middle school. Better to say I have a nonbinary gender identity. A gender identity can’t be frivolous, because it doesn’t mean anything at all.

Most of all, gender identity is defensible. If your reason for transitioning is epiphenomenal, it offers no crack into which to wedge the thought that you ought to be doing something else.

Desire is indefensible: strange and vulnerable and shameful, too intense and too revealing and not at all politically correct. It has only this to say for itself: that it’s the only good reason to do anything at all.

Halperin remarks that one of the most ancient and hallowed traditions of gay male culture is being embarrassed by gay male culture. About fifteen minutes after the first showing of Mildred Pierce, there arrived the first thinkpiece about how all these Joan-Crawford-loving faggots are setting back the cause of gay rights and surely the next gay generation, wholesome and masculine, will prefer football or, if that’s too much of a stretch, Love, Simon.

Sure. And lesbians will stop writing novels about sad, beautiful men in tragic love, or at least refrain from setting those novels in the Harry Potter universe. Trans women will put away their cat ears and anime girl avatars, and henceforward will only wear sundresses in socially appropriate situations. And I won’t feel the delightful frission of being known when a (cis, straight) friend says “why are there so many trans guys like you—who don’t want to be men, just not to be women?”

In the meantime, the Queer Classics series at my local indie movie theater still has Joan Crawford in heavy rotation.

Being gay and being trans are both ultimately about desire—overflowing, ungovernable, persistent in defiance of all good sense, most of all inconvenient. It makes sense, I think, that so many of us feel embarrassed about our desires and the queer culture that reflects them. Other minority groups are defined by ancestry or social position or biology. Queerness alone is defined by wanting.

It’s scary to want, even at the best of times. Scarier if, as Andrea Long Chu says, you don’t want what you should. It feels safe to retreat to an identity that’s almost a tautology, to not stand in front of an uncaring world and say that you will take what you want, because you want it and you can.

This post made me think a bit again of how i didnt figure out that im gay untill a few years ago.

Im raised mormon and super used to fighting against my human nature and desires.

Despite having more teen experiences about attraction to men being positive, it never occured to me that i might be gay. I never even googled “gay porn” until i was 21

You have to in a sense want to want something to allow yourself an identity.

I wonder if theres something here.

Hm

Sorry for a very incoherent comment

It's a good argument, and yes, queer theory has struggled with the term queer since the dawn of time. This is why certain queer scenes work much better than the generalistic high school GS Alliance, because it's about want: wanting leather, wanting to write slash fiction in peace, wanting to hang somebody up by their feet.

However, the beautiful umbrella of 'gay identity' or 'queer identify' is a way of operating on a path before you know your desires. Desiring is hard, pitching tent in an identity is easy. I suppose you could say that this in itself is the desire for something other than straight cis Ness. However, I feel that falls short.

On the other hand, it actually allows for a mass to spring up that has not historically existed: we're making up 14-25% of the population, I hear! Who are we? No idea, but we're killing the numbers game - which is in large part, an exercise in empathy. Like, I think I rarely desire the same thing some straight trans woman do, we almost desire the opposite. Except we both desire to break free from an oppression by the straight cis majority. And that's a good desire to share. Thus, queer as an identity does work, in certain cases.