I.

The most popular model of animal welfare is the Five Freedoms model. The Five Freedoms are:

Freedom from thirst, hunger, and malnutrition, by providing ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigor.

Freedom from discomfort and exposure, by providing an appropriate environment including shelter and a comfortable resting area.

Freedom from pain, injury, and disease, by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment.

Freedom to express normal behavior, by providing sufficient space, proper facilities and company of the animal’s own kind.

Freedom from fear and distress, by ensuring conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering.

A common complaint about the Five Freedoms is that the fifth one is really the only important one. The reason we care about thirst, hunger, discomfort, exposure, pain, injury, disease, and the absence of normal behavior is that they cause distress and mental suffering. If an animal is hungry but doesn’t suffer about it, their hunger doesn’t present a welfare problem.

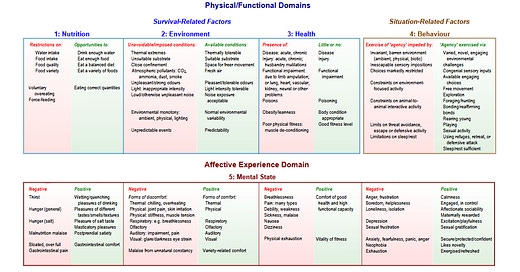

In fact, the Five Domains model (a variant of the Five Freedoms) goes so far as to diagram the Five Domains with mental state across the bottom to convey that it cuts through the other four:

The problem is that it’s hard to measure whether an animal is suffering. Experimentally determining an animal’s level of wellbeing is expensive and complicated; even once you get the results, they’re often difficult to interpret and sometimes pose deep philosophical issues.1 The Five Freedoms2 are useful as a sort of checklist: when you’re trying to figure out if wool sheep have okay lives or developing criteria for your beef-cow welfare evaluation program, you should think about hunger, thirst, disease, injury, temperature, etc. You should also include any information you happen to have about animals’ emotions. But if the data are unclear or unhelpful, you can rely on the common-sense assessment that no animal likes having parasites or breathing in ammonia.

Another interesting question is “normal behavior.” To the best of my knowledge, there isn’t significant or interesting disagreement about what makes for normal behavior for any common domestic species. Chickens need to peck and dust-bathe and form flocks of three to twenty birds. Your cat needs to hunt and scratch and climb up very high to survey the space around her. “If you don't give your working dog a job, they will assign themselves one. Unfortunately, that job may sometimes be eating the couch.”

And yet “normal behavior” is surprisingly difficult to ground philosophically. It’s normal for chickens to have to flee predators, but no one would say you should release a wolf in your henhouse now and then to improve the chickens’ welfare. Sure, the chicken’s preferences matter in determining natural behavior, but you can make a shrewd guess about normal behavior for chickens without once doing a forced-choice study.

If you read articles about animal welfare, you see the same words over and over again: what animals “naturally” do, what they “evolved to” do, what they’re “supposed to” doing, what they “should” be doing, what a “good life” is for them.

II.

I am a capabilitarian because I believe in the Five Freedoms model of human welfare. A high-welfare human has adequate food and water; lives in a comfortable environment; is free of injury, disease, and pain; has the capacity to perform normal human behaviors; and is free from unnecessary and unwanted negative emotions while enjoying a wide range of positive emotions.

It is somewhat easier to figure out if humans are happy than it is to figure out if animals are happy. For one thing, humans are capable of using language. But figuring out whether humans are happy is also expensive, complicated, difficult to interpret, and philosophically thorny.

For example, the book The Origins of Happiness points out that, according to the research, economic growth doesn’t increase overall life satisfaction. Having more money is correlated with higher life satisfaction, but other people having more money is correlated with lower life satisfaction, and these two effects almost exactly balance out.3 The Origins of Happiness argues, apparently seriously, that this means that economic growth doesn’t leave people better off, because the only reason wealth increases people’s well-being is that it lets them feel superior to others. I notice that money lets me buy various things I value—mood stabilizers, a computer, a washing machine, not crying myself to sleep because I can’t figure out how to pay my rent and I’m going to be evicted, Lovecraft-themed tea mugs—so I conclude this is a problem with life satisfaction measures.4

To the best of my knowledge, all direct, statistical measurements of happiness present similar problems. They can be used, carefully and judiciously, to inform our estimates of what a good life for humans is—but, ultimately, we have to make judgment calls like “economic growth is good because humans have higher welfare when they can afford to buy food and treat their diseases.”

There is, I think, more disagreement about “normal behavior” for humans than for chickens. Aristotle and his followers are very influential on Amartya Sen’s and Martha Nussbaum’s writing about capabilitarianism, but neither would agree that the purpose of human life is philosophy (as Aristotle taught) or knowing and loving God (as the Scholastics taught). I think the quest for a single telos of humans is a mistake. Humans, like other animals, have a wide range of normal behaviors—and here I borrow from Nussbaum’s list of central capabilities:

Creating and appreciating art.

Telling and hearing stories.

Learning about the world.

Performing useful work.

Having sex.

Forming friendships.

Forming relationships with animals.

Raising children.

Going out in nature.

Resting.

Participating in the political life of their community.

Playing.

Experiencing sensory pleasure.

Practicing a religion.5

This is not a complete list.

Our complex societies have lead to numerous behaviors which humans didn’t evolve to do, but which they ought to have the capacity to do:

Reading.

Doing basic mathematics.

Using the Internet.

Voting.

Owning property.

Seeking employment.

Assembling to petition the government for redress of grievances.

Similarly, this is not a complete list.

Some of these capacities enable people to perform other normal behaviors in a more complicated society than the one we evolved in. For example, reading helps people learn about the world, hear stories, and perform useful work; voting helps people participate in their community’s political life. Some of these capacities create societies which do a better job protecting the Five Freedoms for humans.6 For example, to a first approximation, democracies don’t have famines: democracy protects against horrifically bad governance, and so makes sure that people have enough food. Similarly, secure property rights make countries richer, which means the country has more resources with which to meet its people’s needs.

Nussbaum thinks—and I agree—that three human behaviors are particularly important to protect. The most normal of all normal human behaviors, if you will. These are:

The ability to form a conception of the Good and plan your own life to pursue it.

The ability to form loving relationships with others.

Being treated with respect and dignity, as a person whose innate worth is the same as any other person’s.

These behaviors get to the core of what it is to be a human: most of all, we are rational, social beings.

The first one puts human welfare in a thorny position, compared to animal welfare. If a chicken doesn’t dust-bathe, we can assume that she doesn’t have the ability to dust-bathe. But if a human doesn’t eat or have sex or create art or form friendships, she might not have the capacity to do these things—or she might have formed a conception of Good and planned her life in such a way that it means being a fasting, celibate, inartistic hermit. For this reason, I think, we should make sure humans have the ability to perform natural human behaviors, but shouldn’t attempt to mandate people actually performing them.

How do we figure out what behaviors are normal for humans? I think cross-cultural anthropological work is enlightening. Which behaviors do humans always perform, regardless of culture7—especially behaviors without a clear and obvious survival benefit? Further, I think qualitative research is promising: I think we should interview people about what a good life looks like for them and what activities they’d do if their lives were truly happy.

Ultimately, when I’m thinking about human welfare, I tend to prioritize the first three Freedoms. Right now, the most pressing issues are making sure that all humans have enough to eat and drink; exist in comfortable environments; and don’t suffer from preventable or treatable pain, injury, or disease. Few fourth-Freedom issues can be ameliorated as cost-effectively as issues related to the first three. And fourth-Freedom issues are often particularly difficult for outsiders to address: your friends are the best people to support you in taking time to rest; the people of a particular country are best-placed to advocate for political freedoms. But I think having a broader perspective on my goals still helps me think through my priorities when I try to improve the world.

Or Five Domains, whatever.

Outside the United States, where economic growth makes people happier.

My guess as to what’s going on is that people compare themselves to others. If no one you know is being evicted, you don’t think “my life is going well because I haven’t been evicted.”

I think Nussbaum left this one off her list because she’s an atheist, but it’s obviously on there.

And of course some do both.

I honestly put a nonzero probability on the idea that it’s a basic human right to be allowed to do fiber arts.

How do capabilitarians deal with INDIVIDUAL lack that isn't really (or only minimally) socially mediated? So, not people who choose to be celibate, but unfuckable incels. Not "child free" but "infertile". Not "solitary by choice" but "fundamentally unlovable asshole".

We're such a disgustingly hypersocial species that many of our key needs require not just being neutrally tolerated by other people but positive engagement from them. And I think much misery in affluent places (so after survival has been dealt with) stems from the fact that some people, usually via a combination of genetics and nurture, however inherently valuable in a philosophical sense, are just very unattractive as social connections. And providing them with that would require forcing others.

Similarly, normal human behaviour involves a lot of intraspecies aggression. Some of it goes beyond ritualused games to serious injury, homicide, war and genocide. It's bit like your wolf example but within species.

"I notice that money lets me buy various things I value—mood stabilizers, a computer, a washing machine, not crying myself to sleep because I can’t figure out how to pay my rent and I’m going to be evicted, Lovecraft-themed tea mugs—so I conclude this is a problem with life satisfaction measures.4"

Rent tends to increase when other people's income increases, so maybe that's the mediator of the effect that The Origin of Happiness speculates about?