Disclaimer: For ease of writing, I say “effective altruism says this” or “effective altruists believe that.” In reality, effective altruism is a diverse movement, and many effective altruists believe different things. While I’m trying my best to describe the beliefs that are distinctive to the movement, no effective altruist (including me) believes everything I’m saying. While I do read widely within the effective altruism sphere, I have an inherently limited perspective on the movement, and may well be describing my own biases and the idiosyncratic traits of my own friends. I welcome corrections.

I.

To effective altruists, the most important academic fields (outside of the natural sciences) are philosophy, economics, and history.

Economics I will talk about in the next post, and philosophy pervades the series. Let’s talk about history.

To be sure, effective altruists care about a specific type of history. Effective altruists are relatively uninterested in history of aesthetics or history of religion, and are bizarrely uninterested in intellectual history. Compared to professional historians, they care relatively little about ethnic or gender history. Compared to the general public, they care relatively little about Great Men (TM) or about wars.

What is left? Political history, to some extent. Social history, in the sense of the lives and experiences of ordinary people. Historiography. And, most of all, economic history.

Effective altruists are good historical materialists (not that that gets us any credit from our Marxist friends). To an effective altruist, the most important fact about history is technology: how a society produces food, clothing, and weapons. Everything else is a superstructure growing out of the base.

Relatedly, effective altruists like grand, sweeping historical narratives, so-called Big History. (This, too, puts them at odds with conventional historians, who tend to prefer narrow, discrete projects of the sort that produce journal papers and PhD theses.) And effective altruists tend to have converged on a specific narrative of history that goes something like this—

II.

Thomas Malthus was the unluckiest social scientist in history.

He was a genius! He discovered what was possibly the most important principle governing human society, all around the world, from the most primitive hunter gatherer tribe to the glories and grandeur of Tang China. If you take the effective altruist view of history, it was one of the most important insights ever made about humanity. If he had discovered it at any other time, he would have been heralded around the world for his wisdom and intelligence.

But he discovered this principle exactly when, for the first time in the history of anatomically modern humans, it stopped being true. So everyone scoffs when they hear about Malthus. “Isn’t he that guy who doesn’t believe in technological development and economic growth?” they say. “If you’re worried about famines, just have a Green Revolution. Easy! What a fucking moron.”

Malthus’s basic insight is: the population can’t grow exponentially forever, because the land only produces so much food. Therefore, in the long run, births have to be equal to deaths. That is, either the human race has fewer births than biologically possible (through chastity, late marriage, or birth control) or lots of people die (through famines, murders, wars, or diseases).1

Some people think that Malthusianism means that everyone is eking out a life barely above the starvation level. That isn’t true. Imagine three societies:

Society A is a stereotypical Malthusian society: everyone is almost starving all the time, and if anything goes wrong they do starve.

Society B has epidemics sweep through every three years that kill a twentieth of the population each time.

Society C is very murderous. About a quarter of the men die young of violence, often in their twenties, before they have children.2

All three societies are at the Malthusian limit: births equal deaths. But Society B and C will be relatively wealthy compared to Society A. In order for enough children to survive to die of epidemics or murder, they need to have enough to eat.

But (before birth control) rich Malthusian societies always pay for their wealth, in disease or in violence or in chastity. Cities, for example, are disgusting hives of disease—perfect population sinks to keep your farmers well-fed. The European Marriage Pattern—marriage in one’s mid-twenties, with a third of people never marrying—probably kept Europe rich; so did Europeans’ poor hygiene. The economic history book A Farewell to Alms notes that many of the pre-colonization Pacific Islands were both relatively wealthy and relatively healthy, a status they achieved by killing between two-thirds and three-quarters of children at birth.

Sometimes a society can be kicked out of equilibrium for quite a long time. Europe was quite wealthy for centuries after the Black Death killed half the population.

Does technological development help? No. A Farewell to Alms presents numerous charts that persuasively argue that—although the data is obviously quite spotty and economic historians need to make a lot of judgment calls—British people in 1800 spent about the same percentage of their resources on food as early agriculturalists and hunter-gatherers, and ate about the same number of calories as a result. Some agriculturalist groups, such as the infanticidal Pacific Islanders, ate more and worked less than British people in 1800.

In the short run, better crops or better farming techniques, improved buildings or variolation, make people in your society richer. But Malthus always wins. People use their wealth to keep their kids alive. The population grows. There is less per person. Soon, you’re back where you started. Everyone is exactly as rich as they were before; you just have a higher population now.

What changed after 1800? Because of the Industrial Revolution, technological growth took off. For the first time, economies started reliably growing faster than the population grew. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution and its consequences decreased births instead of increasing them.3 For the first time in human history, on a societal level, wealth doesn’t trade off against lifespan. A newborn can expect to live to 80 and always have enough to eat.

The past is awful. Effective altruists have a well-rehearsed set of facts about that: about four-fifths of people lived in extreme poverty; half of all children died before they turned five years old. Those facts weren’t bad luck, or because societies were badly run or people lacked personal virtue. There was no other way it could be, not for long.

From an effective altruist perspective, from the Agricultural Revolution until the Industrial Revolution, nothing happened. Oh, sure, empires rose and fell. Kings demanded petty honors and took offense at petty slights; at their whim, cities were sacked and thousands died. Philosophers debated great ideas, and scientists probed the mysteries of the world. Explorers mapped the globe; languages and crops and religions spread. Cathedrals and palaces and coliseums rose and crumbled. Great books and works of art were created and lost. But behind it all, the iron law of Malthus worked itself out. In the long run, births must equal deaths. Restrain yourselves sexually, or spread diseases, or kill, or starve.

And then, one day, it stopped.

III.

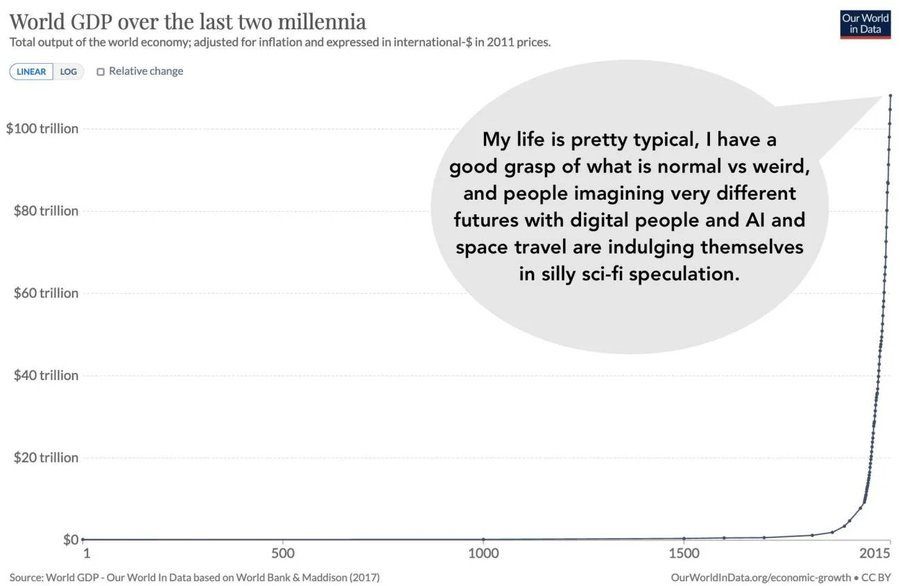

The second thing effective altruists believe about history is that we live in a very interesting time.

And Our World In Data’s chart is understanding the case, because it starts in the year 1. In reality, it should be 150 times as long and the line at the end should look completely vertical.

Exponential economic growth can’t go on very long. If we continue to grow at current rates for another eight thousand years, and if we spread through the galaxy, we would need to support multiple economies the size of Earth’s—per atom.

So—effective altruists argue—over the next few thousand years we have, broadly speaking, four options:

In the next century or so, we reach a state of technological stasis. No one ever invents anything as transformative as the steam engine or vaccines or computers, ever again. The future society remains basically recognizable to us for the rest of time, the way that a peasant’s life in Warring-States-era China is basically recognizable to a 17th century Russian serf. (Call this the “Star Wars” option.)

We (or a descendant species) grow until we create a society as incomprehensible to us as ours would be to that 17th century Russian serf. Or a hunter-gatherer from 10,000 B.C.E. Or a chimp. Or a fruit fly. Then our descendants reach technological stasis before we’re fitting in multiple Earth economies per atom. (Call this the “Accelerando” option.)

Our civilization collapses and we’re returned to some point on the flat part of the graph. (Call this the “A Canticle for Leibowitz” option.)

We go extinct. (Call this the “Planet of the Apes” option.)

Regardless, we live in one of the, like, ten most interesting centuries an Earthling can live in. Fifteen tops.4

Effective altruists believe that, in addition to being interesting, the next few centuries are potentially very influential. That is, our destiny isn’t predetermined: our own actions will decide whether we end up in Star Wars, Accelerando, A Canticle for Leibowitz, or Planet of the Apes. We might also shape the nature of the Star Wars or Accelerando we wind up in, if we (say) get to decide the traits of our successor species. If Star Wars or Accelerando is going to be great, we want to get there as fast as possible; if they’re going to suck, we might want to delay.

Once you accept that you’re definitely in one of the most influential ten centuries, it doesn’t take that much evidence to move you to the position that you’re in one of the most influential ten decades, or even one of the most influential ten years. You might, for example, look at some of the latest developments in bioengineered pandemics or artificial intelligence.

Some people say “lots of people thought that the world was going to end, and all of them were wrong.” But apocalypse predictions fall into two broad categories. One is religious; incontrovertibly, predictions of religious apocalypse have a terrible track record.

The other category—runaway climate change, environmental devastation, nuclear war, bioengineered pandemics, unaligned AI—consists of people who are saying “wow! We’re standing here on the vertical line! Everything is changing very quickly. We’re gaining an enormous amount of power over the world, and it doesn’t seem like we’re using it responsibly. Things can’t go on like this forever, and I’m worried that when it stops it will be a catastrophe.”

I, uh, don’t think that’s an insane position? We haven’t been on the vertical line for very long at all, from a historical perspective. At this point, assuming an apocalypse is impossible is like saying “playing chicken with cars is perfectly safe, we’ve been accelerating for two minutes and we haven’t crashed yet!”

To effective altruists, leaving open the possibility of radical change is the humble position.

Some of my readers might have objections to me including this section in a general effective altruist introduction. Surely there are normie effective altruists who exclusively donate to GiveWell top charities and never think about any of this science fiction shit. Perhaps the normies can be surgically separated from the rest of the community and no longer have short-AI-timelines weirdos dragging them down.

Maybe there are some effective animal advocates who don’t care about science fiction shit (although they’re all weirdos for caring about shrimp). But global health and development? Look at the last word! “Development” is economic growth.

Most GiveWell top charities get at least some of their benefits through increasing consumption—which is to say by making people richer, which is to say economic growth. And there’s not a magic line drawn somewhere between serious, respectable economic growth and science-fiction economic growth. It’s the same thing! By donating to GiveWell top charities, you are implicitly saying “I think Accelerando/Star Wars is going to be fantastic, we should get there faster.”

You might not be interested in science-fiction shit, but science-fiction shit is interested in you. Effective altruists are at least intellectually honest about this fact.

Malthus called contraception and outercourse “vice” and thought that famine and epidemics were preferable because they didn’t involve committing sins. I said Malthus was a genius, not that he was a good person.

Many hunter-gatherer societies are like Society C.

Partially because of contraception, partially because women have more control over their life choices, partially because children are less economically valuable.

When I showed my beta readers this draft, they started arguing about how interesting the fifth century B.C.E. was, a fun game you can also play in the comment section.

This is genuinely the best, and most persuasive explanation of the accelerationist/doomer argument I've read. Thank you, *thank you* for not saying, "Everyone knows this stuff, you're dumb for disagreeing, and if you want more details please read these eight ten-thousand word, rambling manifestos from a crazy person." In my experience, that is the default response, and it's so dismissible and foolish.

...You know what? I'm not even going to argue. My initial reaction is to point out how seldom trends continue indefinitely in any field, and try to poke holes in the whole idea. But I recently made an observation that comments on an article tend to provoke immediate responses over good responses. The correct thing to do would be to think about this and see if my doubts hold water before reflexively dismissing it.

so what I'm hearing is, the gay in FALGSC is a key functional element,