Facts I Learned From Maoism: A Global History (Part One)

Maoism: A Global History is densely packed with both stories and insight, which means that my factpost about it is leaving out about as much as I put in, even though I have split it into two parts. I highly recommend the book to any reader interested in 20th century geopolitics, the psychology of dictators, or Chinese history.

-

Often, the charisma of historical figures is an informed attribute: you read the sentence “General So-and-so was very charismatic”, and you take it on faith because the historians probably didn’t make it up and there isn’t a better explanation for why so many people went along with it when General So-and-so decided to have them charge the machine guns or whatever. Mao isn’t like that. Mao is charming and funny and a delight to read about, and he almost manages to make you forget that he’s one of the worst people who had ever lived.1

Mao was born a peasant and acted like one for his entire life. He wore pajamas or ratty bathrobes to important state functions. He refused to ever brush his teeth. He made crude jokes in important political speeches. He chewed on tea leaves after he drank his tea. He loudly admitted his ignorance: for example, he once told a Brazilian delegation that he didn't know where Brazil was.

Perhaps Mao’s most entertaining moments were when he was bullying the Soviets:

Mao expressed his disdain by eschewing the en suite bathroom in favour of a chamber pot (brought all the way from China). When Khrushchev invited him to a performance of Swan Lake, viewed from the Soviet leader’s special box, Mao announced – by his doctor’s account – that he was leaving at the end of the second act, grousing: ‘Why don’t they just dance normally?’

Mao concentrated on enraging Khrushchev. First, he accommodated the Russian in a mosquito-infested suburban guest house without air conditioning. Next, he forced Khrushchev to meet by the swimming pool in Zhongnanhai. Mao was a famed swimmer; Khrushchev got by with inflatable armbands. After a few preliminaries, Mao removed his bathrobe and proposed that the conversation – about the current political situation – continue in the water. Off Mao went, with Khrushchev – clad in satin trunks, a knotted handkerchief and inflated float aids – struggling in his wake; an interpreter delicately wove between the two leaders of the largest Communist powers in the world. Mao delighted in asking complex questions, in response to which Khrushchev could only splutter, having swallowed mouthfuls of water.

When in 1965 the Soviet premier Kosygin asked Mao whether he could consider a Sino-Soviet rapprochement, Mao replied that he had pledged to denounce the Soviets for 10,000 years. As a special concession, he would reduce that time period by a millennium, but further than that he could not go.

I love him.

In one speech, Mao said that nuclear war was fine because, even if half of all people died, the remainder would have lots of children and would be anti-imperialist and socialist:

After they had recovered themselves, the leaders of the Polish and Czech parties objected that although China was populous enough to survive a nuclear attack, Poland and Czechoslovakia would be obliterated. When the Italian Communist leader, Palmiro Togliatti, voiced a similar reservation with regard to Italy, Mao smoothly responded: ‘But who told you that Italy must survive? Three hundred million Chinese will be left, and that will be enough for the human race to continue.’

Mao was pretty bad to women. He divorced his wife, didn't tell her, and left her to find out from rumors or newspaper articles. Twice. (Different wives.) His first wife was executed because she refused to denounce him, after he divorced her without telling her.

He cheated on his wives constantly and deliberately infected his girlfriends with STIs. For a time, foreign students studying Maoism and guerilla warfare did ballroom dancing on Saturday nights, "to overcome the inhibitions of the feudal days of interaction between men and women." Mao kept a bedroom next to the ballroom, so that he could conveniently go there with any woman he found attractive.

Starting in the late 1930s, Mao learned that an easier way to intellectual respect than learning things is simply declaring yourself to be an intellectual. So he ordered his writings to be treated as a canon, magazines to call him a genius, and study groups to prioritize his writing over that of Marx, Lenin, or Stalin. That said, Mao (or his ghostwriters) was actually a good writer: he wrote simple, compelling narratives, full of both classical references and crude jokes.

I'll give the final word on Mao to one of the author's interviewees:

As a devoted Chinese collector of Mao memorabilia told me in 2014 (in a turn of phrase that is perhaps my favourite in the thousands of conversations that I have had on Mao): ‘Mao was better than Genghis Khan because he was a poet.’

-

Maoism is anti-imperialist, but not because of any anti-imperialism that China ever actually got up to. The USSR was always much more successful at funding anti-imperialist groups. Mao himself was a vocal supporter of anti-imperialism, but mostly because he was never super clear on the distinction between "global Communist anticolonial revolution" and "everyone thinks Mao is really great."

Why? Partially, Mao could get off a really good anti-imperialist witticism when he felt like it. Partially, it was historical coincidence. The People’s Republic of China formed at about the time that a wave of decolonization hit, so it enthusiastically took credit even though it had played very little role. Partially, China under Mao acted in such an insane self-destructive way that many revolutionaries concluded it must support global revolution.

And partially Maoism is anti-imperialist because of what China symbolizes. The People’s Republic of China offered a third way: neither the US nor the USSR. Maoism was a real, powerful political ideology that didn’t come from Europe or America. It claimed to be particularly suited to the needs of rural, agrarian countries. Orthodox Marxism, in contrast, offered little for agrarian countries; Marx believed that countries would have to be capitalist for a century or two before they could have a Communist revolution. And even today, people in many developing countries view China as rich because of Maoism.

Maoism is a pernicious ideology because it’s actually really good at winning insurgencies. The violent, militant nature of Maoism makes it suitable for wars. And Mao was legitimately talented at guerilla warfare; his writings contain much useful advice for the aspiring revolutionary.

The problem is that, even compared to other Communist ideologies, Maoism is a godawful way to govern a country.

Maoism supports continuous revolution, "ceaseless, violent shake-ups of the political establishment." Even though Mao was an absolute ruler, he always saw himself as an outsider who tried to destroy the party infrastructure. The Cultural Revolution came from something deep in Maoist ideological DNA. To some extent, Mao felt most comfortable as a guerilla leader; his solution, when he felt uncomfortable in his political position after the failure of the Great Leap Forward, was to govern his country in a way as close to fighting a guerilla war as possible.

Similarly, Maoists believe in "voluntarism," the idea that The People can accomplish anything if their will is strong enough, regardless of the obstacles. Voluntarism is a convenient belief if you are running an insurgency. Sometimes, voluntarism leads to an ill-advised lack of planning: for example, the Indonesian probably-Maoist September 30th Movement launched its coup on October 1st, out of sheer disorganization. But most of the time, voluntarism is useful for the guerilla: it doesn’t benefit you to doubt whether the war is winnable.

On the other hand, if the question at hand is “can the peasants make these grain quotas?” or “is it possible to make steel in a backyard furnace?” or “if we implement these policies will everyone starve to death?”, it is very very bad to assume that all obstacles are due to inadequate willpower and can be easily overcome if The People just want it hard enough. Material conditions are real and they can hurt you.

-

One meeting of the New People’s Study Society – a radical cell co-organised by Mao in Hunan – spent much of its time deliberating whether the society’s aim ought to be ‘to transform the world’ or to ‘transform China and the world’. The associates then came up with the following list of hell-raising measures to achieve their goal: ‘Study; propaganda; a savings society; vegetable gardens.’ Once those key decisions had been taken, the society turned its attention to the all-important programme of ‘recreational activities’: river cruises, mountain excursions, spring outings to visit graves, dinner meetings, frolics in the snow (arrangements to be made whenever it snowed).

-

A swimming pool was under way and the trainee revolutionaries volunteered to help dig it. It did not take long before the construction workers tactfully asked the ‘foreign student comrades’ to ‘kindly do their work, i.e., study and let them do theirs, i.e., build the swimming pool’.

-

Maths teachers tested students with revolutionary sums: 'Following Chairman Mao’s statement in support of the African-American struggle against tyranny, 17 platoons of eternally red, revolutionary elementary school students and teachers immediately engaged in protest demonstrations and resolutely endorsed Chairman Mao’s mighty statement. On average, each platoon had 45 people. Altogether, how many people participated in protest?’

-

Some testy colonial official scribbled in the margins of an intercepted copy [of Malaysian Communist Party propaganda]: ‘It must be very tedious for the…communists to have to read through this stodgy stuff…I can’t really believe that we have the technique to win the hearts and minds of chaps like this.’

-

In the 1950s, the Bank of China had special "bureaus" where people could write letters to overseas relatives asking for money, a term which here often means "bribes not to execute them."

In 1950, women began to be able to sue for divorce, and many wanted to divorce their husbands who had been overseas for years or decades. The Chinese government mostly didn't let them because it might interfere with the remittances. However, they did let the women have affairs. One cadre had more than ten girlfriends who were the wives of overseas Chinese men.

During land reform, the wealthy families of many overseas Chinese were executed—but then the remittances stopped! So the party developed a policy of "preferential treatment." The relatives of overseas Chinese people got to shop in special stores that were stocked even when there were shortages of certain goods. They sometimes even lived in "New Villages" where they could maintain a wealthy lifestyle.

In 1956, during the Great Leap Forward, the CCP reversed itself once again and enslaved everyone.

-

During the Cultural Revolution, books by and pictures of Mao had been the safest choice of ceremonial gift. In one (perhaps apocryphal) story, a couple received 102 copies of Mao’s works as wedding presents. Enough portraits of Mao had been manufactured for each Chinese person to own three.5 More than a billion Little Red Books had been printed.6 Now billions of volumes of Mao’s works were mouldering in warehouses: not only were they taking up space needed for post–Cultural Revolution manuals on modernisation – Deng Xiaoping was agitated about how far behind China had fallen in science and technology during the late Mao era – they were also responsible for 85 million yuan in bad loans, and required round-the-clock guarding by a specialist army division. (Despite their best efforts, about 20 per cent of Mao’s books succumbed to cracking and mildew, thanks to unsteady temperatures.) The CCP resorted to radical solutions. On 12 February 1979, the Propaganda Department banned the sale of the Little Red Book and – barring a few copies to be held in reserve – ordered all extant volumes to be pulped within seven months. Up to 90 per cent of remaindered Mao-era political books were turned into mulch – including the entire run of the fifth volume of Mao’s Selected Works.

-

In 1979, Deng Xiaoping ordered the development of the official party orthodoxy on Mao. It went through nine drafts to properly balance praise and criticism. The final document referred to the Great Leap Forward famine as "serious losses" and characterized the Cultural Revolution as a series of understandable mistakes. Everything bad about the Cultural Revolution was attributed to the Gang of Four, whom Mao was clearly working against. In 1993, Deng himself said that much of this document was "not true."

-

One of the reasons that Mao can't be dropped from Chinese politics is that he's the founder. The USSR could reject Stalin and valorize Lenin; the PRC has only Mao. Imagine if George Washington had caused the deaths of millions of people. Americans would also have a rather confused set of attitudes about him.

-

In the spring of 2000, a Singaporean friend invited me to watch a new musical in Beijing – Qie Gewala (Che Guevara). Alternating between episodes evoking the life of the Argentinian revolutionary, and scenes located in noughties Beijing, the show resonated with a Cultural Revolution aesthetic of Manichaean struggle, in which Mao-era revolutionary morals were contrasted with the spiritual vacuum of contemporary China. Its cast was divided into two groups: goodies (all played by men) versus baddies (all played by women). When a good character tried to do something good – for example, rescue a drowning child – a baddy would stop him (by arguing that the child lacked economic value and was therefore dispensable). ‘Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong, we will follow you in a hail of bullets and shells,’ pledged one song. The audience roared approval. At a Q&A with the cast afterwards, the thirty-something director berated himself and his fellow modernised urbanites for ‘spending too little time, too little time in contact with the labouring people’.

-

Neo-Maoists are a distinctive Chinese breed of enraged Internet poaster. They are notable for being angry, anti-West, and aggressively nationalist. They believe Deng's reforms happened because "revisionists and capitalists" stole power from the proletariat. Revisionists are traitors allied with foreign imperialists. All problems in Chinese society indicate the need for a 'continuous revolution' to purify the party, and possibly a new Cultural Revolution. Every problem on China's frontiers, from Taiwan to Xinjiang to Tibet, is the United States's fault and is best resolved by being tougher on the United States. Intellectuals are reactionary imperialist traitors. (Of course, many neo-Maoists themselves have college degrees.)

The CCP is deeply ambivalent about neo-Maoists. On the one hand, they can't reject the neo-Maoists without rejecting the Maoism from which Xi Jinping derives a lot of his legitimacy. On the other hand, neo-Maoists are a source of political unrest. They see themselves as persecuted by the CCP, which coexists easily with the belief that they are the true defenders of the CCP and everyone who dislikes them doesn't like the CCP.

I can’t help but imagine the poor bureaucratic functionary who has to deal with these people. He must have such a headache. I feel bad for him!

-

The author visits a neo-Maoist commune:

he decided to withdraw from the pugnacity of wired leftism to found his own utopia on a collective, organic farm in Hebei Province, south of Beijing. The influences were a befuddling mix of Thai Buddhism and veneration for Mao, though Han did not see any contradiction. ‘Mao is a Buddha. The Buddha wants to deliver all living creatures from torment, and Mao wanted to liberate mankind.’ I queried his Buddhist definition of Mao, given the chairman’s veneration of political violence. A nationalist answer came back at me. ‘There are two legs to Maoist thought,’ he explained, ‘violent class struggle, and serving the people…Class struggle comes from the West. Serve the people comes from Chinese tradition.’ Bad Western influences therefore corrupted Mao’s Buddha-like instincts and caused the brutality of the Cultural Revolution...

One consequence of Han’s suspicion of experts, I presumed, was the surfeit of squashes around the farm; the whole place seemed to be tangled with vines and their gourds. Han admitted there was such a glut that they were making an experimental shampoo out of them. He seemed unduly impressed by my ability to identify carrot plants from their feathery leaves.

-

Compared with the Mao craze, the cult of Xi is – it must be said – pale and unconvincing. Stacks of his Collected Works gather dust in bookshops; for almost twenty years, the propaganda outlets for Xi worship – People’s Daily and CCTV – have been losing audiences. Transmogrified from the Mao era, China is now a country where everything has a price, even in left-leaning media – across one Maoist website I visited, my attempt to read articles about ideology was slowed by a roving pop-up trying to sell me plush towels in the design of the banknote that carries Mao’s image.

Six months after its publication in the UK, the second volume of Xi Jinping's collected writings had sold less than 100 copies. Embarrassing!

-

56 Flowers—named for the alleged unity of the fifty-six official ethnicities in China—is a pro-CCP idol group modeled after Kpop idols.

-

During the Korean War, the Chinese coerced POWs into accusing the US of germ warfare (the United States denies using germ warfare to this day). Experts in the US blamed the accusations on brainwashing that rewrote the POWs' minds.

In the summer of 1953, a deal was brokered where POWs were released and allowed to choose between North Korea, South Korea, Taiwan, and the PRC. (Presumably, American POWs released under this deal would then return to America from whatever country they picked.) Of the 3,597 Americans released, 23 chose the PRC. This caused an uproar in America. Tens of thousands of American students wrote letters begging the POWs to come back to the U.S. As a result of the pressure, two POWs decided to instead come back to America, leaving 21 defectors to the PRC.

Obviously, the only reason this could possibly have happened was terrifying Chinese brainwashing.

[T]he majority of American POWs who did choose to return home were not sent back immediately to their families. They were brought back by ship, which took a fortnight to reach the US. Officially, the army wanted to give them ‘good food and plenty of rest’. In fact, Washington generals used these fourteen days for intensive psychological profiling to detect Communist mind-moulding. Psychiatrists, spies and detectives swarmed around the prisoners, shoving booklets of questionnaires into their faces. The interrogations – which could go on for eight hours at a time – did not end on the boat home. Not satisfied with the two feet of dossiers that they had put together, FBI agents visited and revisited so-called RECAP-Ks (Returned and Exchanged Captured American Personnel in Korea) for years.

By 1956, it was clear from records about POWs that the PRC had access only to standard techniques of hunger, exposure, torture, and persuasion. American POWs engaged in "thought reform" and "consciousness raising" programs which involved "small-group discussions and criticism/self-criticism, individual interrogations, the writing and rewriting of autobiographies and confessions." These programs were in some ways professional: for example, staff spoke good English and often had gone to American universities. But discipline could be lax. American POWs often made fun of the classes or simply slept through them. Defectors usually had reasonable motivations for defecting: for example, one defector was black and tired of antiblack racism in the United States.

One reason the US foreign policy establishment believed this insane stuff about brainwashing because they didn't know much about China. Throughout the 1950s, Chinese speakers and people with friends in China were treated with suspicion by the State Department—if not as outright traitors. Most people who were analyzing Chinese brainwashing didn't speak Chinese and knew very little about China.

By 1960, the U.S. government had devoted billions of dollars to attempting to reverse engineer Chinese brainwashing that didn't in fact exist. The most famous—and horrific—attempt to do so was MK-Ultra (the next quote is highly disturbing):

On more than a hundred human guinea pigs, Cameron gave them a daily dozen of electric shocks; kept them in comas for up to eighty-six days continuously; and forced them to listen, for fifteen hours at a time, to simple negative or positive messages about their personalities. One woman came out of the treatment unable to remember her three children. A middle-aged depressive would only drink milk from a bottle and forgot how to talk.

The fear of Chinese brainwashing played a remarkable role in U.S. foreign policy. For example, anti-colonial efforts in Malaysia and Vietnam were attributed not just to Chinese Communist efforts but specifically to Chinese Communist brainwashing. The "domino theory"—that if one country was lost to the PRC, so would the rest of Southeast Asia—emerged in 1948 and was closely tied to unrealistic ideas about the PRC's brainwashing capabilities. Similarly, the Chinese diaspora was believed to be full of brainwashed double agents. Brainwashing offered a convenient explanation for geopolitical events, such as Communist insurgencies, that might make the West look bad.

-

Many hippies saw the Cultural Revolution as the successful version of the Summer of Love or as "one long, fantastic, libertarian fiesta." Many hippies' Maoism was basically apolitical: it was less about any specific approval of Mao and more about owning those in authority. They preferred Mao to the Soviets because the Soviets were staid and boring. Continuous revolution seemed more fun.

-

It became so easy to win China’s confidence by proclaiming oneself a Maoist that the Dutch secret services set up one such party, led by a maths teacher, as a front for gathering intelligence about China. The ploy remained undiscovered all the way up to the Dutch government dismantling it after 1989.

-

the [Chinese] embassy was so deluged by demand for Little Red Books from pupils at another prep school that it was forced to write them a letter – read out in assembly by the headmaster – asking that no more copies be requested.

-

Shirley MacLaine visited China and wrote a travel memoir called You Can Get There From Here. It praised the food prices (low), the streets (free of drugs and crime), the children (hardworking), the women (uninterested in clothes and makeup) and the relationships (monogamous).

Her book ended with a paean to Chinese authoritarianism. ‘I as one who aspired to art and the supreme importance of the individual, was changing my point of view as to just how important individualism really was…I was seeing that it was possible somehow to reform human beings and here they were being educated toward a loving communal spirit through a kind of totalitarian benevolence…Maybe the individual was simply not as important as the group.’ A year after returning from China, she concluded that Mao’s dictum to ‘serve the people’ was also a personal instruction to ‘serve myself’ and opened a one-woman, high-kicking cabaret in Las Vegas, announcing (while draped in zircon-studded peach chiffon) to perplexed reporters on the first night that ‘Mao Zedong is probably responsible for my being here’.

-

French Maoists did hard manual labor and mostly discovered it was horrible. Some of them had the energy to harangue their coworkers about Mao and discovered that absolutely no one wanted to listen.

The rhetoric of the French Maoists was violent. But in 1972 they rioted, a worker died, and the leader of the riot fled the scene while crying from guilt. After that, the French Maoists took up pacifism.

-

Jean-Paul Sartre once tried to Get To Know The People by having dinner at a worker's house, ate rabbit stew, and nearly died from an asthma attack.

-

‘A housewife used to modern kitchen and cleaning appliances’, [a West German Maoist group] hopefully conjectured, ‘would have no difficulty using a machine gun.’

-

The Black Panthers made latecomers to meetings run laps while reciting quotes from the Little Red Book.

-

As a political praxis, Black Panther women refused to have sex with men unless they knew the Little Red Book and the Black Panthers' platform.

-

‘Power comes out of the lips of a pussy,’ the sex-obsessed Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver would sometimes say; at other times it came ‘out of the barrel of a dick’.

-

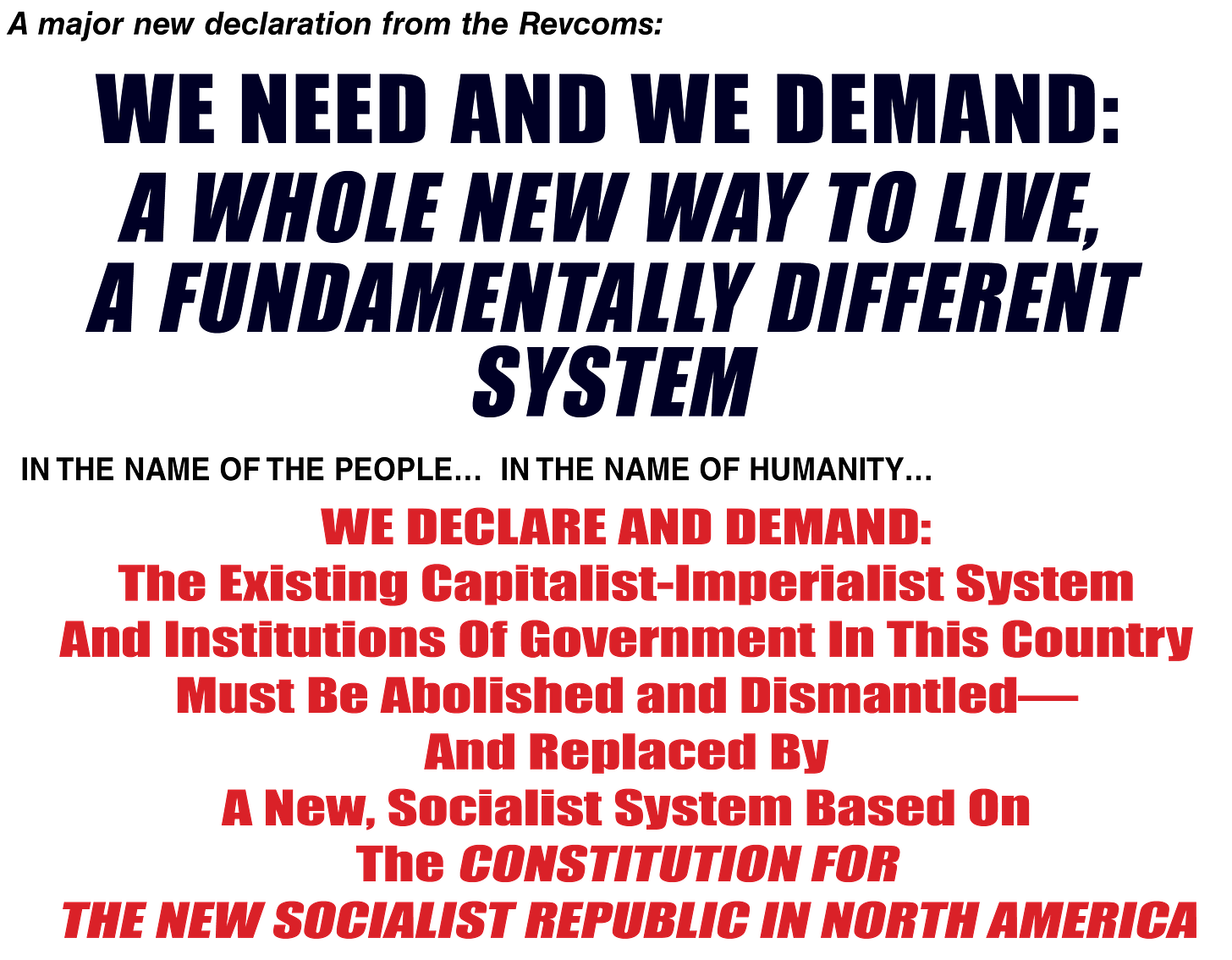

So. Bob Avakian. You know Bob Avakian? The guy whose followers keep putting up posters like this all around the Bay Area?

Yeah. It turns out he influenced the Nepali Maoists into starting a revolution? At their peak success, the Nepali Maoists ruled 80% of Nepal. Today, Nepal is the only country outside of China where Maoists hold national political success. Surprising amount of success for a guy who puts up bad posters in the Bay Area.

Avakian is explicitly pro-Shining-Path. I’m going to talk about the Shining Path in the next post; for now, just understand that this is a sentence like “he is explicitly pro-Hitler.”

-

The male members of the [German] commune [Kommune 1] also happened to be coercively promiscuous: ‘whoever sleeps twice with the same woman, already belongs to the establishment’. One of their number asserted that his orgasm was ‘of greater revolutionary consequence than Vietnam’.

-

Feminist theorist Julia Kristeva went so far in her support for Maoism as to argue that footbinding was an expression of female power, apparently not knowing that Maoists had ended footbinding.

-

In Italy:

‘In the name of Mao’, militants had to give up all luxury goods to the party: books by ‘bourgeois’ authors, record players, mopeds, hair-dryers and toasters, all of which would be sold off to generate money for political campaigns. The only politically correct consumer items were plaster casts of Brandirali: one hand raised in a clenched fist, the other clutching a baby. From 1973, the group also policed its members’ sex lives, decreeing that ‘orgasm must be simultaneous’, with masturbation, anal and oral sex all prohibited because they were ‘manifestations of a petty-bourgeois mentality’.

-

Two young American radicals, one a Maoist and one a Trotskyist, once decided to settle whose politics were correct by reading the works of their respective favorites to marijuana plants. The Maoist plant thrived, the Trotskyist plant died, and the obvious conclusion was that only Maoism will lead us to revolution.

-

Zhou Degao, the PRC’s faithful foot soldier in Cambodia, was cut utterly adrift. Marginalised, starved and almost executed by the Khmer Rouge, he made his way to China in 1977 to present a deeply critical report of the CPK. But officials in Beijing bawled him out for lacking discipline, for meddling in the affairs of the Central Committee, for criticising their best ally in Indochina. Completely disillusioned with the Chinese government and disgusted at his mistreatment by uncouth apparatchiks, Zhou fled China and renounced his CCP membership. ‘I was a patriotic idiot,’ he concluded. After toiling on menial jobs in Hong Kong, he eventually succeeded in emigrating to the United States. Although he served out his working life as a school cleaner, unable to put his education and experience to proper use, he ended his autobiography with a paean to the ‘liberty and security’ he experienced in his adopted home, this ‘free country, with rule by law’, whose B-52s only three decades earlier had been pulverising his native Cambodia.

One of my beta readers said that none of these anecdotes were charming and actually Mao seemed like a horrible person with no redeeming qualities. She is possibly a better person than I am.

Awesome post, only tangentially related: I find a lot of earlier writings/attitudes about sex to focus a lot on simultaneous orgasms? Some societies (medieval somewhere?) have thought it necessary for pregnancy, and I have some book on sexology from the 50's that eagerly assure the reader that it's okay and normal not to have simultaneous orgasm.

Am I the only one who very rarely has exact simultaneous orgasms? Such an expectation would stress me out. They are hard to time so precisely!

"And even today, people in many developing countries view China as rich because of Maoism. [...] The problem is that, even compared to other Communist ideologies, Maoism is a godawful way to govern a country."

i think this is being unfair. it omits the rather obvious and epoch-defining economic development in china under mao: by most estimates, a nearly 10x increase in national gdp; by world bank estimates, an increase in life expectancy of nearly 20yrs (interrupted by the great famine, its true, but recovering very swiftly); and a generally acknowledged vast improvement in literacy, nutrition, medicine, and general standard of living. by the numbers, this was outpaced significantly by deng et al, but even setting aside any concerns abt the character of that later development, they were building on a bedrock laid by mao. its not ridiculous for ppl in the undeveloped world to look at the economic progress made under maos direction and see in it a model for their own advancement

i should probably disclaim that im not saying this out of any ideological partisanship. im not a maoist, nor even a marxist-leninist, and indeed only a marxist at all in a pretty loose sense. i do not think mao would crack my top 50 in favourite historical world leaders, and idt that the economic gains afforded by the mao-era prc somehow justify or excuse the obvious cases of mismanagement and senseless violence. but i do think, if you are going to heavily weight the "hockey stick" graphs on various measures of well-being in assessing the merits of capitalist industrialisation in the west, the least you can do is extend similar charity to socialist collectivisation in the east.