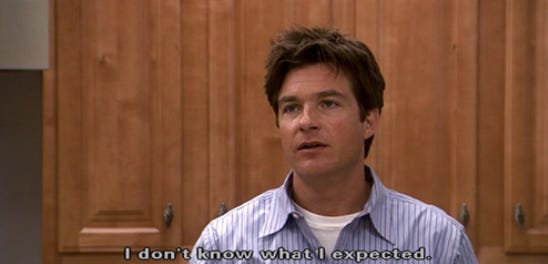

This is me upon learning that one of the Inklings started a cult:

It was a nice cult, though. A very sedate British cult that didn’t do any spiritual abuse or weird sex. A tea-and-cake-with-the-vicar sort of cult.

Charles Williams was born in 1886 in London. (Throughout his life, Williams adored London and considered it to be an earthly expression of the City of God. ) His father lost his job and his eyesight, which necessitated the family moving to the countryside. It also left his father with an extraordinary amount of time to spend with his son, which they spent going on long walks and discussing literature and philosophy. Williams’s father taught his son that there were many sides to every argument and that you should never misrepresent the facts to advance your opinion. Although they were both Christian, Williams’ father taught Williams to admire atheism and atheist figures. In adolescence, Williams began to write poetry, which he shared only with his father; his father offered encouragement and constructive criticism. Williams also spent much of his time creating an elaborate secondary world with his sister and a friend from school.

At sixteen, Williams won a scholarship to University College, London, but when he was eighteen his family ran out of money and he had to leave. After a few years of working as a clerk, Williams found a job as a proofreader at Oxford University Press’s London offices. Over the course of the next twenty years, Williams would be promoted to the editorial department, because of his love for poetry.

In 1908, Williams met Florence Conway, who would become his wife. Conway was intelligent but not very intellectual. She scolded Williams for reciting poetry loudly in public places; he nicknamed her ‘Michal’ after Saul’s daughter who made fun of David for dancing before the Lord. In a triumph of mixed signals, he once gave her an eighty-four-sonnet sonnet sequence addressed to her but themed around the idea that one should renounce love for the sake of God. Eventually, Williams read Dante, who convinced him that love of a human might lead you to love of the divine, and resolved some of his conflicts here. A mere five years later, he and Conway married. Their marriage was troubled: Conway was practical and domestic, while Williams was obsessed with poetry, theology, and mysticism. Still, Williams was emotionally dependent on his wife and said that he would do poorly without her.

In his late twenties, Williams became interested in ritual magic and was initiated into the Order of the Golden Dawn. Williams’ particular faction was led by A. E. Waite, who discouraged the practice of white magic and outright forbade the practice of black magic. Waite believed that the Golden Dawn’s practices were part of the “Secret Tradition” of Christianity, hidden practices that were revealed only to the elect. For this reason, Williams believed that being a member of the Order was entirely compatible with his Christianity. He eventually left the Order, although we’re not sure when.

In 1924, Williams fell in love for the second time, with a woman named Phyllis Jones. She was the librarian at Oxford University Press. They didn’t, by all accounts, have sex, and Williams never considered divorce from his wife.1 But he courted her with an endless series of poems. After only a few months, she broke up with him, for two reasons. First, he wanted her to write response poems to all his love poems to her, which was unreasonable when they arrived practically every day. Second, he liked to make her write essays about the English poets, grade her, and spank her hand with a ruler if she didn’t get a good enough grade. (This appears to have been a reflection of Williams’ sexual sadism.)

After the breakup, Williams was thrown into a tremendous depression, and as a result entered an astonishing period of artistic creativity: within the next few years, he wrote seven novels, an assortment of nonfiction books, and an Arthurian poetry cycle. Williams wrote novels for the money. He was constantly broke, partially because he was thoughtlessly generous and kept giving to the needy and buying presents for friends when he really couldn’t afford it. Fortunately for Williams, he considered the desire for money to be the best stimulus for great art. T. S. Eliot said of Williams that "he always boiled an honest pot."

Williams’ historical nonfiction was quite easy for him. As he was an enthusiastic autodidact, he just wrote down whatever he already knew about the historical figures and sent it off to the publisher. His Arthurian poetry cycle sold poorly because it was completely incomprehensible if you weren’t a member of Williams’ cult (of which more in a few paragraphs, I realize I did promise you a cult).

During his period of artistic creativity, he also taught at the Evening Institutes. The Evening Institutes educated the working classes, mostly in vocational occupations, but also in art and music and literature for those who wished to broaden their minds. Williams taught English literature and was a phenomenal teacher, in the sense that he was a phenomenon. He spoke too quickly for anyone to take notes. He sat on the table and gestured dramatically. He typically lectured on Milton, Shakespeare, and Wordsworth, although he sometimes taught modern poetry or even Dante (who presumably was Assigned English Poet At Williams). His lectures rarely contained any facts; instead, they focused on conveying to the audience what it felt like for him to read a poem. He quoted enormous amounts of poetry from memory, usually from poems that weren’t the poem he was discussing. He seemed to feel that many points were best made in quotes from Milton or Dante rather than in one’s own words. Williams’ own enthusiasm made the discussions afterward enthusiastic. After the discussion was over, someone would always ask to speak with him, sometimes about poetry but often about their personal problems. His students saw him as a wise man, the nearest they could get to one of the great poets like Shakespeare.

And that flowered into Williams’ cult.

Williams’ cult was nonconsensual on Williams’ part. His disciples insisted that they wanted to be a group with a name, and eventually he gave in. They were referred to as “the Household,” “the Company,” or “the Companions of the Co-inherence.” Most were young woman, who tended to find Williams extremely attractive. Although he was rather ugly, he was so charismatic that few of his female followers noticed.2

Williams’ cult had three primary teachings. First, “co-inherence,” the idea that every action affects other people, everyone is dependent on everyone else, good acts may lead to evil and evil acts to good, and that ‘sin’ is the refusal to act in accordance with the pattern of the universe. Second, “Romantic Theology,” the idea that romantic love could bring one closer to God. Third, “Substitution” or “Substituted Love,” the idea that you could pass along anxiety, despair, or even physical pain to another person who had voluntarily chosen to take that pain on. The Companions of the Co-inherence often practiced Substitution.

Williams almost never referred to God, Christ, or the Devil. He called God "the High God" or "The One Mover"; Christ "The Crucified Jew," "the Divine Hero," "the Revealer," "Messias"; the Devil "the Enemy," "the Infamy." He also said "under the Protection," "under the Mercy," and "under the Permission."

Williams didn’t believe in the Devil as a person, though he often wrote about black magic. He believed the Devil was a way of making people feel better about their own disobedience to God by imagining someone worse than themselves. The cause of evil, according to Williams, was people imagining something other than pure goodness; the Fall, the wish to know the antagonism to Good.

As a manifestation of Romantic Theology, Williams regularly wrote passionate love letters to the female Companions.3 However, as far as we know, he never had sex with any of his Companions. None of the female Companions complained of being sexually abused or bragged about being an object of his sexual attention. (A few remarked on, for example, uncomfortable hugs.)

His Companions were encouraged to confess their sins to him. He assigned penances to them, such as copying out or memorizing Biblical passages. Overall, the Companions were very mystical, and the influence of Williams’ past in the Order of the Golden Dawn is obvious.

Meanwhile, C. S. Lewis had stumbled across one of Williams’ novels. At the same time, Williams was proofreading a nonfiction book of Lewis’s. They wrote fan letters to each other simultaneously and, as you might expect, promptly arranged a meetup. They became friends, but sadly they lived in different cities, limiting their friendship. In 1939, however, World War II broke out, and Williams’ branch of the Oxford University Press was evacuated from London to Oxford—where Lewis lived.

Lewis thought that Williams was the best person in the world. His feelings for Williams that bordered on the romantic. Lewis on Williams:

He is of humble origin (there are still traces of Cockney in his voice), ugly as a chimpanzee but so radiant (he emanates more love than any man I have ever known) that as soon as he begins talking he is transfigured and looks like an angel. He sweeps some people quite off their feet and has many disciples. Women find him so attractive that if he were a bad man he could do what he liked either as a Don Juan or a charlatan.

Also Lewis on Williams:

If you... saw Charles Williams walking along the pavement in a crowd of people, you would immediately single him out because he looked godlike; rather, like an angel.

Lewis arranged for Williams to lecture on poetry to Oxford’s undergraduates. He also dragged Williams off to join the Inklings. With the Inklings, for the first time in his life, Williams was interacting with men who knew more than he did. Williams greatly appreciated the opportunity for argument and criticism of his poetry.

Unfortunately for everyone involved, Lewis was a carrier of Geek Social Fallacy #4: Friendship is Transitive. Williams was not nearly as beloved by the other Inklings as he was by Lewis. One minor Inkling, according to Lewis’s letters, "almost seriously expressed a strong wish to burn Williams, or at least maintained that conversation with Williams enabled him to understand how inquisitors had felt it right to burn people."

Tolkien was first introduced to Williams by Lewis declaring Williams to be the most wonderful person and Tolkien would love him, and then sort of shoving them together at the Inklings’ meetings while going “BE FRIENDS!” Tolkien was, naturally, jealous. For nearly ten years, Tolkien had spent every Monday morning talking alone with Lewis, and suddenly Williams was there every single time, and they kept talking about boring things like English literature that came out after Chaucer, and Lewis kept saying stuff like “in every circle that he entered, he gave the whole man” and as far as Tolkien saw No He Did Not.

Tolkiens’s complaints about Williams multiplied. He found Williams’ poetry incoherent and not properly mythical. Tolkien was turned off by Williams’ interest in black magic, which was present in much of his stories. Tolkien believed the devil was real and methods of interacting with him should not be put in novels. Lewis was, however, blissfully ignorant of Tolkien’s dislike and continued to shove his two best friends together and insist that they loved each other. Grudgingly, Tolkien seemed to have accepted this new state of affairs and even begun to get along with Williams. However, the best evidence the author of this Inklings biography can find for this claim is a letter from Tolkien that begins “I was and remain wholly unsympathetic to Williams' mind,” so take it with appropriate grains of salt.

Tolkien did, however, write a three-page poem in praise of Williams, of which the first two pages are devoted to complaining about how incomprehensible Williams’ poetry is. The last few lines:

When your fag is wagging and spectacles are twinkling,

when tea is brewing or the glasses tinkling,

then of your meaning often I've had an inkling,

your virtues and your wisdom glimpse. Your laugh

in my heart echoes, when with you I quaff

the pint that goes down quicker than a half,

because you're near. So, heed me not! I swear

when you with tattered papers take the chair

and read (for hours maybe), I would be there.

And ever when in state you sit again

and to your car imperial give rein,

I'll trundle, grumbling, squeaking, in the train

of the great rolling wheels of Charles' Wain.

In this period, Williams wrote a book about Dante and religious theology. Lewis described it as "the clearest thing he had ever written" and forbade him to edit it. Also, T. S. Eliot visited the Inklings. His visit was enjoyed by no one except Charles Williams, who thought the disaster was very funny.

On May 15, 1945, less than a week after World War II ended, Williams died. His cult died with him. He would never be able to read the Narnia books, or the completed Lord of the Rings.

The Inklings, by Humphrey Carpenter. Published 1978. 304 pages. $18.70.

This did not make his wife much more pleased about this state of affairs.

His wife was not happy about this either.

His wife was even more unhappy about this.

Dude, read the novels if you haven’t, they’re amazing. Recognizably from the same planet as Lewis and Tolkien but not really the same continent or, like, sanity waterline. War in Heaven, Greater Trumps, Place of the Lion, All Hallow’s Eve all good bets, save Descent Into Hell for when you’re into it, the only one to avoid is Shadows of Ecstasy which is impossible to find anyway, I hunted down a copy eventually but it’s pretty unreadable. It’s also very worth paging through Poetic Diction if you’re that sort of language person.

Seconding @Shabby here. The novels are bonkers, in a good(?) way. Also they're all available at cwlibrary.com now!