I.

In this post, I adopt a capabilitarian approach to analyzing whether people have the right to an abortion. I’ve written more about my understanding of capabilitarianism here.

Other ethical systems will give different answers, and I’m not going to attempt any sort of complete taxonomy of what different moral beliefs imply about abortion. I do think that one of the strengths of capabilitarianism is that it tries to work within the “overlapping consensus” of ethical systems: we might disagree about a lot, but we agree that it’s good when (for example) people have enough to eat. So I hope this post will be helpful even for people who don’t share my weird ethical system.

II.

The first question to be answered, when considering whether it is wrong to have an abortion, is when it is wrong to kill.

The study of ethical problems related to who is born and how many people are born is called population ethics and it is famously cursed. It is impossible to come up with any sort of conclusion about population ethics that even remotely tracks common-sense intuitions like “it’s better for the world to have a large number of happy people than an incomprehensibly vast number of people whose lives are just barely worth living” and “whether it is right for me to have a baby shouldn’t depend on whether aliens exist.”

I normally try to dodge population ethics questions whenever I can. My usual take is that I leave it up to the individual whether they want to create a person, but killing people who already exist is wrong. But why is it wrong? Why is death usually bad for you?

Some people argue that death isn’t bad for the person who died.1 After all, she isn’t around to have an opinion on the subject. She didn’t exist for billions of years before her birth, and it wasn’t wronging her that she didn’t exist yet. In this view, death itself isn’t bad, but it causes other bad things: the pain of dying, the survivors’ grief, other people’s fear of death, etc.

This seems wrong to me. I want to be alive. I would be pretty unhappy about dying even if I died painlessly and no one would miss me.

Okay, so, let’s work with the “I want to be alive” thing. It’s good if people have things they want, and most people very badly want to be alive, so it’s wrong to kill them.

But this theory is unsatisfying. I (like most people) think it’s wrong to kill two-year-olds, but two-year-olds don’t really understand what death is and I don’t know that they could be said to have a preference about the subject. It’s true that the death of two-year-olds could be bad for other reasons like pain and the survivors’ grief. But that implies that, all things equal, it’s less bad to kill a two-year-old than an adult. I, like most people, think that it’s worse to kill a two-year-old than an adult.

So I think death is bad in some way unrelated to the person’s preferences about the subject and—what is more—I think death can be bad even if you don’t understand what death is.

One theory I find plausible is the deprivationist theory. Death is bad for you because your life was going to have good things in it, and now you’re not going to get to have those good things.2 Death is bad in the same way that missing lunch with your friends because you have to go to the dentist is bad, except it’s every lunch you were ever going to have. This seems to lead to pretty intuitive results: we generally agree that death is less bad if you have nothing to look forward to but misery. We usually think a death is less bad if the deceased was in a lot of pain from their illness; conversely, we usually think a death is worse if the deceased had a lot of pleasurable things to look forward to.

Another theory I like is Martha Nussbaum’s life-projects theory. People generally have various ongoing life projects: raising children, maintaining friendships, designing a better stapler, getting promoted, writing novels, learning to sew, binging Bridgerton on Netflix. Death is bad because it interrupts your various life projects.

This theory is annoyingly squishy (what exactly is a “life project”?). But I think it does a really good job of tracking what we actually think is bad about death. My great-grandmother died when she was over a hundred years old. We were sad, of course, but not that sad. It was her time. And what does “it was her time” mean? It meant that her husband had been dead for decades. Her children and grandchildren were all grown. She couldn’t work. In general, she didn’t have a lot to do other than read the large-print versions of smutty romance novels and fight the assisted-living bureaucracy about whether she belonged in the nursing home instead.

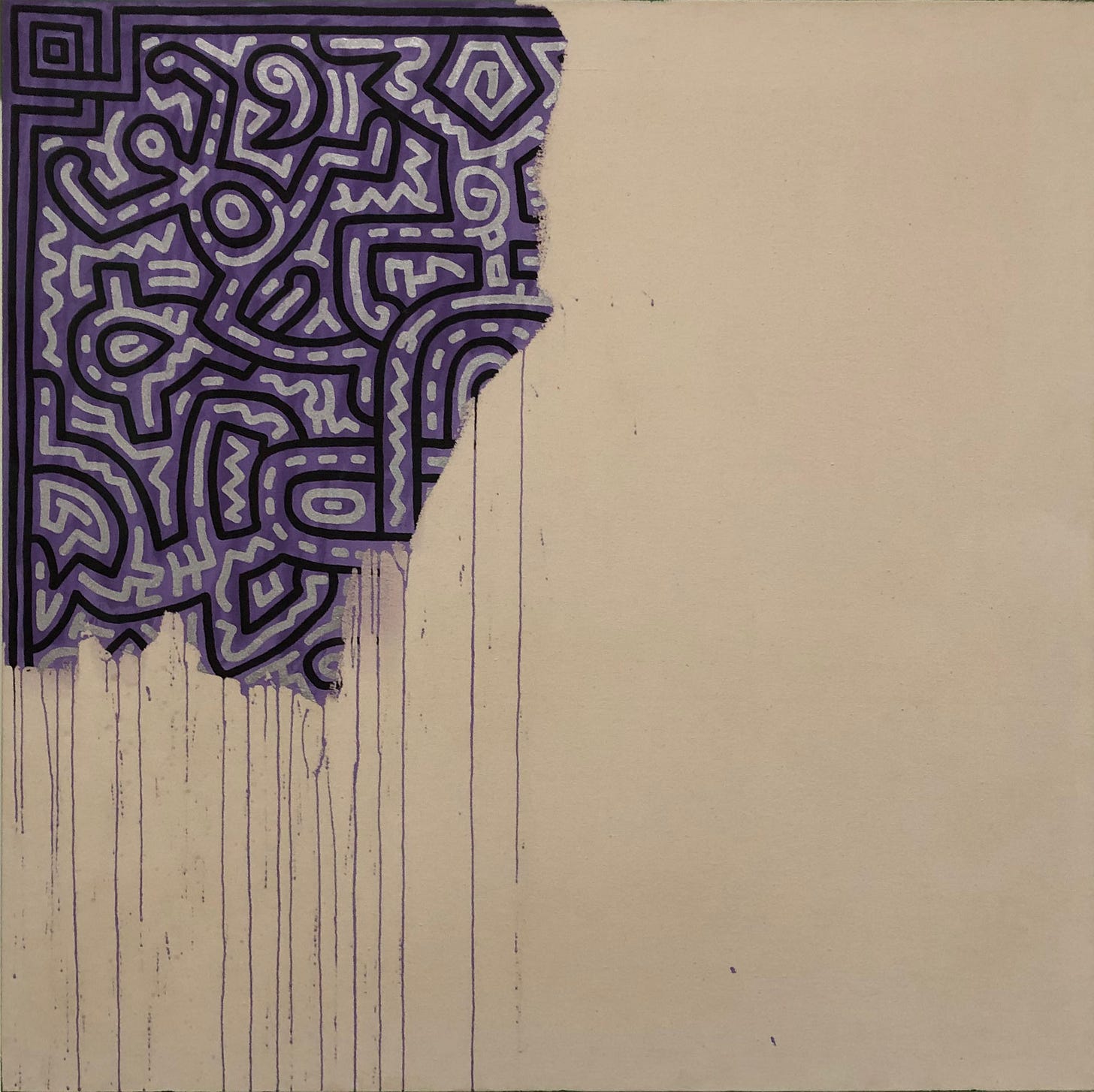

Conversely, when talking about what makes a death truly tragic, people often talk about unfinished life projects: he never got to see his kids grow up; she never got to play basketball for UC Berkeley like she’d always dreamed of; he never got married; she had always wanted to travel the world. One of my favorite paintings about death is Keith Haring’s Unfinished Painting, one of his last works before he died of AIDS, which despite the title was exactly how he meant it to be:

Unfinished Painting, to me, eloquently captures a harm of death: He wasn’t done yet.

A child who is killed is denied an entire lifetime’s worth of good things. And Nussbaum argues—and I agree—that all children have, in addition to their other life projects, one vitally important life project, perhaps the most important of all: to grow up.

So the death of a child is a particular tragedy and one we are well-motivated to avoid.

III.

This is bordering on population ethics, so someone might end up telling me that my beliefs imply we should genocide every left-handed person on the full moon. But I think that what I said before—about life projects and the deprivation of good things—only applies to actual people and not potential people. If you have procreative sex in the morning rather than the afternoon, you’re not killing the baby you would have conceived if you’d had sex in the morning.

So at what point do potential people become actual people? As suggested by my example above—and the casual attitude people typically have to ejaculate and menstrual periods—eggs and sperm are potential people.

Conversely, six-month-olds are actual people. But where does the line flip over?

Many people think that personhood begins at conception. Conception has some nice qualities for this purpose: it’s one of only a small number of hard cutoffs between “egg cell” and “six-month-old.”3 Birth isn’t a hard cutoff in the sense I mean: presumably 39-week-old babies matter just as much regardless of their current location. But there is a real difference between a zygote and an egg.

But “conception” has some very counterintuitive implications. Let’s say you’re trapped in a burning building and you have a choice between saving one five-year-old and a thousand frozen embryos.4 If you’re not both pro-life and chronically addicted to biting bullets, you pick the five-year-old, right? Very few people really think that embryos’ lives matter as much as born children’s do.

Conversely, let’s say you’re trapped in a burning building and you have a choice between saving one five-year-old and two premature infants born at 21 weeks of gestation. A lot of people are going to pick the infants. Even the most hardened personhood-grows-in-at-nine-months pro-choicer is going to find this one a little difficult.

So we can guess that personhood probably grows in somewhere between conception and 21 weeks gestation.5 My proposal is that—instead of a hard cutoff—personhood actually grows in gradually over that time period.

This may seem counterintuitive to you: either a being matters morally or it doesn’t. But lots of people accept similar arguments. For example, it’s wrong to torture a dog. But it’s worse to torture a human than to torture a dog, and if you have a choice between torturing a dog and a human you should torture the dog. In general, we act like some beings matter more than other beings: that is, that they have more “moral weight.”6 In fact, I think common-sense morality has more gradations of moral weight than most ethical philosophers would grant: common-sense morality says it’s worse to torture a child than an adult, but most philosophies say you’re supposed to treat all humans equally.

It seems to me that it’s a little bit wrong to kill an embryo: at least, I’d take more care with an embryo than I would with a menstrual period. And it seems to me that it’s not quite as bad when a child dies at 21 weeks of gestation as when a newborn dies. But the largest changes seem to me to happen somewhere in the conception-to-21-weeks period.

IV.

I always found the violinist argument a weak argument. Of course you’re supposed to save the violinist, I said. He’s a person! It’s just nine months.

Then I got pregnant.

It was very much a wanted pregnancy, and my child is currently a healthy, happy six-year-old. But at some point, probably between the two months I spent unable to do anything but read undemanding fiction and the time I vomited out the window of an car on the highway so I didn’t mess up the Uber driver’s upholstery, I realized that forcing anyone to go through this against their will is an atrocity.

I think this is the truth behind the slogan “no uterus, no opinion.” You don’t lose your right to do moral reasoning based on your internal organs. And ideally everyone is capable of exercising the moral imagination without personal experience. But some people—like I was—are stupid.

People should have broad and expansive rights related to medicine. An adult should have a legal right to refuse almost any medical intervention, no matter how important the procedure or how stupid their reasons. You should be able to talk to your doctor about your medical conditions, confident that the non-anonymized information will never leave the room without your permission. And if your daughter is dying and only your kidney will save her, and you have plenty of time off for surgery recovery and such fantastic kidneys that you would be in the 95th percentile of kidney function even without one, and your only reason for refusing is that you think the scar would make you look unattractive in a bikini—

Then the doctor should go out and tell your family that you’re not a match.

Medicine is special. It is one of the contexts in which we are weakest and most vulnerable and most dependent: reliant on doctors to tell us the truth about our options; perhaps reliant on others to bathe us and feed us and help us go to the toilet; perhaps even reliant on machines for our hearts to pump and our lungs to breathe. Many of our most humiliating experiences are medical, from Pap smears to diarrhea to psychotic breaks.

Medicine involves making a number of choices with no good answer, choices that come down to our basic sense of what is good. Should you die to follow the teachings of your faith? Should your doctors eke out another day of your life that you spend confused and scared and in pain? How much effort do you spend chasing increasingly unlikely cures for your disability, instead of giving up and trying to find a life worth living as you are? Should you put up with manic episodes that hurt you and those around you, or take mood stabilizers that make you feel nothing at all? Is it worth putting up with daily back pain to make it easier to someday breastfeed your child?

Medicine makes us come to terms with being animals, made of meat, constantly on the verge of breaking down. In spite of all our pretensions and grandiosity, we can be taken down by a glorified strand of DNA or a misfolded protein or a cell that doesn’t know when to stop dividing. And, most of all, in a medical context we face the fact that we are all going to die.

For this reason, medicine ought to put particular effort into treating patients like people. Patients are vulnerable, scared, powerless animals, but they aren’t just vulnerable, scared, powerless animals. They ought to be treated with dignity and respect. And they ought to be given what power they can, especially the most important power at all—to make their own choices that reflect their own values.

I don’t think I’ve ever felt anything as intimate as having a literal human growing inside me—nor can I imagine anything that, if unwanted, would be as invasive. Rape is an extraordinary violation, but your heart doesn’t pump blood through your rapist’s veins.

The right to abortion is related to another profoundly important right: the right to choose whether to have a child.

I understand why feminists hesitate to bring this subject up. If we say “people have a right to choose whether to have a child,” it raises awkward questions about men who have children they never wanted—questions I will not address, except to say that the entire child-support system needs to be reformed from the ground up, and society must not justify neglecting its obligations to poor children by conscripting the man, himself generally quite poor, who is nearest the problem.

The implementation details are complicated, because it takes at least two people to procreate, and we must consider the wellbeing of the created child. But the decision to have a child is the most important decision most people will ever make. It creates a lifelong responsibility which you will never be able to set down. The responsibility is costly—in time, in money, in energy, in the opportunity cost of everything else you will not be able to do. You have an awe-inspiring amount of power over another human being: you dictate where they live, what they eat, what their hobbies are, when they go to bed; you are their only source of information about the world for a long time, and their primary source for a long time after that; within limits, you can even legally assault them. I’m not sure I’ve ever met someone who wielded that power completely ethically, and I’m somewhat skeptical that it’s possible, although fortunately children are resilient to their parents’ moderate moral failings.

And at the same time, having a child is one of most people’s most important life projects; for some, it is the only life project that really matters. Parenthood is many people’s primary source of meaning and purpose, their connection to something greater than themselves. Being someone’s parent is a unique and intimate relationship, a kind of closeness you can get nowhere else. Ask any parent: raising their children well is one of the most important things they will ever do.

Again, it’s very hard to figure out how to give as many people as possible the ability to decide whether to have children. But to say that people don’t have the right to decide for themselves whether to have children makes a mockery of any attempt to say people should be able to decide the course of their own lives. We might as well give up the entire liberal project as a bad job.

Some people will object that not having access to abortion doesn’t mean a person has to become a parent: she can always give up her child for adoption. It’s true that there are far fewer healthy newborns than parents who want to adopt them, and some pregnant people mistakenly believe that if they give their child up for adoption the child will be stuck in the overburdened foster care system.

But adoption doesn’t mean not being a parent. Many people have parental feelings towards any of their biological offspring. Many other people acquire parental feelings over the course of growing an entire person inside them for nine months. To them, adoption isn’t “not being a parent”: it’s being a parent who will never get to watch their child grow up. As you’d expect, giving up a child for adoption often causes profound grief.7 Giving a child up for adoption is the right choice for some pregnant people, but it doesn’t substitute for the ability to end a pregnancy.

V.

Some decisions have no wrong choice, like “should I get pizza or go to the movies?” Some decisions have an obvious morally right choice, whether it is easy to put into practice (“should I hit strangers with hammers for no reason?”) or difficult (“should I hide Jews from the Nazis in my basement?”) But we often face tragic questions: a decision where, although one choice might be the best, in a just society we wouldn’t have to choose either. If you have one heart and two patients in need of a transplant, who gets it? If your donation can save one child from death or lift two from poverty, which should you give to? If you have to work a job that harms people in order to feed your family, what should you do?

Abortion is often a tragic question. On one horn of the dilemma: a pregnancy continues against the will of the pregnant person. On the other: someone perhaps dies.

I am pro-choice, because I can’t see anyone better to answer the tragic question than the person who would have to carry the pregnancy and who is the parent of the child. She has the best knowledge of all sides of the situation.

But the real problem, with any tragic question, is how to keep them from arising in the first place. The obvious answer is to prevent unwanted pregnancy—a subject the pro-life movement, at least in the United States, shows almost no interest in.8 We should improve access to highly reliable contraception such as IUDs and the implant. We should also improve access to emergency contraception, which prevents ovulation (it does not prevent implantation of an embryo).

But there’s another way around the tragic question.

Remember, as an unborn child gets older, it gets wronger to kill them: it is much worse to kill a premature baby than an embryo. Therefore, we should try to push abortions as early as possible. Every abortion of an embryo with a neural tube rather than a brain—of an embryo rather than a fetus—of a fetus that couldn’t survive outside the womb rather than one that can—is a moral victory.

No pregnant person delays getting an abortion for the fun of it. Usually, abortions are later than they would otherwise be because the pregnant person has trouble accessing an abortion. She needs time to scrounge up the money. The doctor is booked up weeks in advance. The clinic is far away, and she needs to take time off work to get there.

Inadequate abortion access is a policy problem, not a medical problem. The abortion pill is safe, effective, and easy to use. There is no reason that it can’t be prescribed virtually, picked up at a pharmacy the same day, and used by the pregnant person for an abortion at home—the same as other widely-used medications, from SSRIs to treatment for yeast infections.9

The pro-life movement, on the other hand, has dedicated itself to making sure that, if an abortion happens, it should be the morally worst abortion possible. The dedication was perhaps brought to its most absurd point by legislation that required waiting periods for an abortion, as if pregnant people are running around impulsively getting thrill-abortions.

Waiting periods are the most absurd; but abortion criminalization is the worst. In the United States, pregnant people in states where abortion is illegal have to fly to another state to have an abortion. Put yourself in the shoes of a poor woman with three kids who got pregnant but can’t afford another child. How is she going to find money for a plane ticket, a hotel room, the abortion itself? Can she get time off work? (Does she even know her work schedule in advance, or does she work as a barista or a grocery store clerk?) Who is going to take care of her children? (What if her husband has to work while she’s gone?) It’s a miracle if she manages to get an abortion in her first trimester.

If abortion is sufficiently criminalized that pregnant people can’t fly to another state for an abortion, the problem is even worse. Forget the safety of illegal abortions—how many weeks would it take to find someone willing to perform one?

Sure, all this prevents a certain number of abortions. If you care about all embryos and fetuses equally, and care more about the embryo or fetus’s right to life than you do about the pregnant person’s right to self-determination, the tradeoff may well be worth it. But if you have qualms about abortion, if you think fetuses do matter but not as much as an adult matters, if you think abortion is always tragic but sometimes necessary—you should want abortion to be easy.

This is called the Epicurean view, after the philosopher Epicurus.

Some people are presently sputtering that this theory requires knowing who “you” is and what distinguishes “you” from someone else, and philosophy of personal identity is almost as cursed as population ethics. However, the problems with philosophy of personal identity mostly come up in science-fictional situations like uploads or Star Trek transporters, so I feel less inclined to avoid it.

Another nice one is the first brain waves at the end of week 8 of pregnancy.

Assume that all the embryos are destined for implantation.

Fortunately, so-called late-term abortions are only about 1% of abortions and usually occur for medical reasons.

Rethink Priorities’ Moral Weights Project is a really interesting example of this.

Today, the standard is “open adoptions,” in which the birth parent or parents play some role in the child’s life. Open adoptions tend to be associated with less grief than closed adoptions.

No, “don’t have premarital sex” doesn’t count. Married people are not in a continual state of wanting a child.

Women on Web is a discreet, safe and affordable way to buy the abortion pill, including in countries where abortion is illegal. You may buy the abortion pill ahead of time and keep it in case you or a loved one need it.

> Let’s say you’re trapped in a burning building and you have a choice between saving one five-year-old and a thousand frozen embryos. If you’re not both pro-life and chronically addicted to biting bullets, you pick the five-year-old, right? Very few people really think that embryos’ lives matter as much as born children’s do.

I think a lot of this is due to presumed replacement effects, though? My instincts about this situation are very different depending on whether the outcome is "these particular embryos burn up, the people involved have a different thousand kids instead" or whether it's "these particular embryos burn up, the people involved have no kids at all instead, the world in five years has a thousand fewer people than it otherwise would have". In the former case, it's pretty unambiguously right to save the five-year-old; in the latter, my common-sense-morality-intuitions point five-year-old-ward but my consequentialism-intuitions point embryos-ward and I'm genuinely unsure which would win in the event. (I'm pretty sure my *endorsed* answer, from a distance, is the embryos, but unsure how much effect that would have on my actual decisions in the moment.)

Very interesting. As someone who thinks that it's much worse for a 10 year old to die than a newborn, and possibly even for an 18 year old too, I'm probably out there by today's standards (and no, I'm not a time traveller from the "massive child mortality" era though this historical perspective undoubtedly plays a role).

As someone who had an abortion which didn't feel like a tragic or difficult decision -- in the sense that I didn't have a doubt for a moment what I wanted to do -- but still felt like a much harder thing to go through than taking a morning-after pill (I think it's this scared animal thing kicking in here) I feel that the concept of gradually "increasing" personhood might be a decent compromise here -- and as on your embryos vs child example, the vast majority of anti abortion people don't REALLY seem to believe that abortion is equivalent to infanticide, never mind "proper" murder.

>> I would be pretty unhappy about dying even if I died painlessly and no one would miss me.

Interesting. Even if you didn't know it was to happen or that you were dying?

I think I'd be ok with it. On some level, it would feel like an optimal, even desirable solution: nobody gets harmed apart from the future me, who doesn't exist. Of course, you're young, so you have a realistically worthwhile future of projects and "projects", rather than just waiting for the (clearly visible on the horizon) decrepitude to arrive; so that makes a big difference.