I.

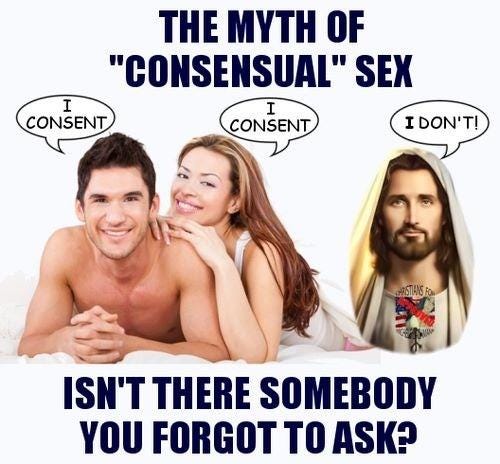

Many people say something like “the only thing you need for a sex act to be ethical is that everyone involved consents.” I think this is an impoverished view of sexual ethics, because it implies that sex is the only area of human life where the sum and total of ethics is “don’t commit violent felonies.”

I get why people say that. 99% of the time, when someone says “you need something other than consent for sex to be ethical,” their proposed alternative is act-based sexual ethics. That is, in addition to requiring that sex be consensual, they come up with a specific list of acts you shouldn’t do: BDSM; gay sex; anal sex; premarital sex; casual sex; masturbation; sex using contraception. As long as everyone is consenting and you don’t do anything on the no-no list, you’re fine.

One problem with act-based sexual ethics is that a lot of people have fulfilling, life-enriching, beautiful sexual experiences that are on the no-no list. Those people are, naturally, disinclined to listen to busybodies telling them that they’re degrading themselves or secretly crying themselves to sleep every night or whatever.

Another problem is that… it doesn’t help? The flipside of “kinky anonymous sodomy can be great” is that vanilla heterosexual sex between married people often isn’t. Married straight vanilla couples can be unkind or disrespectful or even cruel to each other—in bed as well as out of it. I have read a lot of act-based sexual ethicists, and almost none of them are willing to admit this. If you’re lucky, they act like once you say “I do” you’re guaranteed a life of blissful mutuality and respect and orgasms. If you’re unlucky, they start talking about men needing sex every three days and the importance of paying the marital debt.

But sexual ethics is about more than just rape, and almost everyone knows it. So we make consent do more work than it really can.

Some of this work is in the definition of “consent” itself. Whining when your partner says no to sex is surely wrong—but is it the same thing as holding them down and violently forcing them into sex? I don’t really think so. The experiences of the two kinds of victims are, on average, quite different (although of course both can be traumatizing). And conflating the two causes people to underestimate the scope of the latter problem. I’ve met multiple people who thought that 1 in 6 women have ever been victims of rape, in the sense that their partner pressured them into sex they didn’t want. In reality, 1 in 6 women have been forced into sex against their will through force or threat of force, or when they were unable to resist because they were high or drunk or asleep or passed out.

Cheating on your partner is wrong. I have seen people argue that this is because your partner didn’t consent. Who else gets to consent to sex they’re not involved in? Must parents consent to sex their teenagers have? Must my best friend consent to me having sex with his ex? Must Rod Dreher consent to me having degenerate queer sex? He certainly finds the thought of it very upsetting.

I’m not sure we want to set this precedent.

I have also seen people argue that cheating is wrong because your partner can’t informedly consent to sex afterward, which implies it is fine to cheat as long as you make sure your marriage is a dead bedroom.

Some people also expand the category of people who “can’t consent.” Some people, such as small children, certainly can’t consent to sex. But I also see people say that, say, sex with your therapist is wrong because you can’t consent to it. I agree that there are definitely consent issues involved in sex with a person who can imprison you against your will at a whim.

But some therapist/client relationships seem consensual. At least, the client will say that the relationship with their therapist is consensual. They might marry and be together for decades; they might break up, but the client continues to say the relationship is consensual. You might say that actually they’re wrong and they weren’t consenting, but to me this stretches the definition of consent to the breaking point. Overriding adults’ opinions of whether they consented loses the primary benefit of consent-based sexual ethics: treating the individual as the authority on their own experiences. As you might expect, it lets in act-based sexual ethics through the back door: one of the largest anti-BDSM organizations is called We Can’t Consent To This.1

You might go the other way and say that consensual therapist/patient sex is all right. This seems wrong too. Psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder gave Michelle Smith false memories of Satanic ritual abuse, which set off the Satanic panic. They also married and stayed together until Pazder died twenty-five years later; Smith never accused Pazder of rape or anything nonconsensual. It seems likely to me that the relationship was consensual. It also seems likely to me that the inappropriate therapist/patient sexual relationship was a cause of Pazder’s psychiatric abuse of his patient, an so caused Smith tremendous harm.

Consent-based sexual ethics also make it hard to understand sex as an actively good thing that a good society ought to give people access to. The involuntary celibacy case is difficult so I don’t want to address it here. But I do think our society should do more to provide sexual accommodations for disabled and elderly people, instead of assuming that they can simply live without sex. And, though this is taboo to say, we do (and should) accept some increased risk of rape in exchange for more sexual satisfaction. Drug and alcohol use increase the risk of impulsive rapes, but many people find that looser inhibitions or euphoria improve sex a lot.

To me, the obvious conclusion is that whining when your partner turns down sex, cheating on your partner, and having sex with your therapy client are all bad to do—and so are having PIV without contraception when you can’t take care of a kid, taking careless risks of spreading STIs, and having sex with someone when you know damn well they’ll regret it in the morning. Some are more consent-related harms, and some are less consent-related; some of them are larger harms and some are smaller; some can be genuine mistakes, and some are inexcusable; but all of them are wrong even if they aren’t rape.

II.

An interlude concerning BDSM—

Whenever I talk about sexual ethics beyond consent, some kinky people are like “I love being treated like a sex toy,” or “I love my partner not paying any attention to what I want,” or “I love being disrespected when we have sex,” or whatever.

I don’t know your life, I could be wrong here, but I’m going to guess that you probably don’t. What you like is playing a game where your partner pretends to disrespect you, or to ignore what you want, or to treat you like a sex toy. You would be unhappy if, during sex, your partner mocked you for losing your job when they knew that you felt sensitive about it, or noticed you were unexpectedly dissociating and shrugged it off, or ignored all your desires for kinky sex and had nothing but meh PIV for the rest of time.

Saying “I like when my partner disrespects me because I like BDSM” is like someone saying that they enjoy assaulting people with swords and then clarifying that they mean they like boffer LARP. Okay, there are many ways those things are similar, but the fact that one of these is pretend is not incidental to whether it’s a good thing to do!

It’s true that some kinky sex—although it’s relatively uncommon—is closer to actual degradation (within limits and with protection). The analogy in this case is less to boffer LARP and more to mixed martial arts. It’s true that mixed martial arts is similar to assault! But the limits, the protection, and the informed and enthusiastic consent by adults who know what they’re getting into are, again, not incidental to whether this is a good thing to do.

This behavior on the part of kinky people can make it nearly impossible to have any sort of sophisticated conversation of sexual ethics. Please stop.

III.

My proposal—which is admittedly radical— is that sexual ethics is the same as ethics in any other area of life. Like parenting, political activism, and piloting airplanes, there are unique considerations that apply only to sexuality; and like parenting, political activism, and piloting airplanes, most of the same basic ethical principles carry over.

In many ways, my approach to sexual ethics is analogous to my approach to discourse ethics.

You should, in general, only argue with people who want to argue with you.2 But there are lots of other things you should do:

Accurately represent your sources.

Try to understand your interlocutor’s argument fully before you disagree.

Avoid name-calling.

Be willing to change your mind.

Point out flaws in your own argument that your interlocutor might have missed.

Dispute the central point, instead of getting caught up in minor details.

Clearly mark what parts of your argument you’re uncertain of.

Look for high-quality evidence.

Avoid “nutpicking” random people who believe insane shit instead of arguing with the best or most typical representatives of a particular view.

And so on.

You can say “well, I only consent to debates if no one is going to want me to be open to changing my mind! So there.”3 You shouldn’t be forced to participate in debates against your will, like you’ve been kidnapped by Substack Annie Wilkes. But if you don’t want to change your mind, then other people shouldn’t argue with you. And we’re allowed to think less of your character that you have this preference.

In discourse ethics, the line between moral injunctions and good ideas isn’t very clear. Clearly it is both morally wrong and unwise to make fun of your interlocutor’s weight or to fake data. But it isn’t morally wrong to get caught up in minor details: it’s just that if you do that you’re unlikely to learn anything. At some point, you’re misrepresenting sources so badly that you’re doing something morally wrong, but it’s not clear where to draw the line between “morally wrong” and “well, if you were more careful, you’d understand the world better.” I’m enough of a virtue ethicist that I don’t really care; I don’t expect “morally good” and “practically good” to be that extricable anyway.

There’s no point in discourse ethics where you can say you’re done. You can reliably do the basics, like not insulting people. But openness to changing your mind, understanding people you disagree with, finding high-quality evidence—these are lifelong quests. You can get better at them, but you’ll never achieve perfection. Whenever you feel like you’ve got it handled, you’ll discover that once again you’ve gotten invested in your pet belief being right, and you have to go back to the beginning.

These quests aren’t for everyone. Most people will reach an acceptable level of openness to changing their mind—one where they can try a new approach at their job, but probably won’t switch political parties—and stay put. That isn’t even unvirtuous: many people need to focus on being better parents or better bosses or more financially responsible or more generous to strangers, and not on truth-seeking. But pursuing excellence in this area can be very rewarding for those who take it up.

IV.

There’s an important disanalogy between discourse ethics and sexual ethics. Forcing yourself to have an argument you don’t want to have is sometimes bad and sometimes good.4 Forcing yourself to have sex you don’t want to have is almost always bad.

Why? Forcing yourself to have sex usually leads to a bad relationship with your body and your sexuality. It makes you feel resentful of your partner for having a good time while you’re staring at the ceiling doing the grocery list. If your partner is a good person, they want you to have a good time when you have sex; discovering that you forced yourself will upset them, and might even feel like a violation to them. And… sex is supposed to be fun? If it’s not fun for you, it’s kind of going against the whole point of the enterprise.

But this creates a problem for the aspiring sexual ethicist. You might want to say “if you’re in a monogamous relationship, you have some responsibility to make sure you and your partner have a fulfilling sex life”, or “if you’re not attracted to Asian men because you alieve that they’re nerdy and effeminate, that’s bad.”5 But the naive way of implementing those instructions is really bad. It is bad for the high-libido partner, the low-libido partner, and the marriage if the low-libido partner grits their teeth through sex that disgusts them. It is bad for everyone involved if people with racist aliefs are going around fucking people they’re not attracted to out of a sense of moral obligation.

I do want to be clear: you shouldn’t force yourself into sex.6 Nothing I say about sexual ethics should be interpreted as saying you should force yourself into sex.

I think the solution is often to take a step back. What can a lower-libido partner do before they have sex? Maybe there’s a medical condition that needs to be treated, or they need to switch birth control methods or antidepressants. If they’re tired, they might need to say no to more obligations or to ask their partner to provide more childcare. If they don’t enjoy sex, they might need to discover what they want or to express their sexual needs to their partner. If the lack of sex is a symptom of the relationship being crappy, perhaps couples’ therapy is in order. Perhaps the lower-libido partner has more responsive sexual desire, and the couple should schedule no-pressure time together to kiss and cuddle and see if it goes anywhere. Perhaps the lower-libido partner isn’t up for sex sex, but the couple can explore sexuality together in other ways, like sexting or sharing naked pictures or snuggling while the higher-libido partner jerks off. And, of course, sometimes even if everyone involved7 makes a reasonable good-faith effort, the lower-libido partner will want sex less than the higher-libido partner—in which case the higher-libido partner must accept the situation with good grace.

Racism clearly affects people’s sexual desires. But if you take a step back, you get “you shouldn’t alieve that Asian men are nerdy and effeminate,” which has nothing to do with sex at all. It can be easily discussed without mentioning the sexual element and thus risking people forcing themselves into sex. As far as I can figure, the only reason people talk about desirability politics is that arguing about sex is fun—bringing up the subject does almost no good to anyone.

In my next post, I will talk more specifically about what I think about ethical sex.

Note for those clicking through: We Can’t Consent To This, in line with its name, plays up its opposition to nonconsensual violence during sex, but most of its activism is actually opposed to consensual, if risky, BDSM.

Consent to argue is implied if you, for example, have a Substack.

Arguably, many people do.

If, for example, you don’t want to have it because you know it will lead you to admit your cherished belief is wrong.

I in fact believe both of those things.

The main exception is sex work, for people with certain psychologies. I have thoughts about this that are too long for a footnote.

Including the higher-libido partner—don’t be the person who’s like “I don’t understand why my wife doesn’t want sex! Apparently it ‘hurts’ but why would that be relevant?”

Awesome read! Also wanted to point out that viewing sex exclusively through the consent framework tends to put sex work in a weird place. Sex work occupies a weird place in general, but there's some unfortunately mainstream ideas (like the association with human trafficking - when many sex workers aren't trafficked, and many human trafficking victims aren't sex workers. A lot of them are farm, domestic or construction workers).

Great read! One thought, re: 'What you like is playing a game where your partner pretends to disrespect you.' If it is assumed that 'enjoying pretending to be disrespected' has no relationship to 'actually being disrespected' I think it then becomes unnecessarily hard to explain. It seems more likely that it is the ambiguity which is exciting, the risk of slippages between 'pretending to disrespect someone' and 'disrespecting someone' and the more fundamental slippage between pretending and [whatever the opposite of pretending is]. In other words, I don't think 'playing a game' is the right analogy here; at least, in a game like football, there is no ambiguity at all between the rule-bound game and the outside world; if someone breaks the rules, the game stops; the game is a self-sufficient world. It seems that the element of play in BDSM is precisely the opposite of that; the thrill relates to ambiguity. I say this without having any personal experience, though; it just struck me that there is something interesting about how the concept of game is used here.