The Four Guys Who Wouldn't Shut Up And Were Wrong About Everything

Never trust a physicist

I normally recommend people read books that I review on this blog, but I can’t really recommend that for Merchants of Doubt. About 70% of the page space of Merchants of Doubt is taken up with the minutiae of dry corporate memos, who works for what think tank, the exact findings of various presidential commissions, the complete trail of citations separating a factoid from its original, and which scientific journal article was written before which other scientific journal article. But quite often “boring” is the price you pay to buy “credible,” and I do think Merchants of Doubt is a credible book.

The same handful of physicists— Frederick Seitz, Fred Singer, Robert Jastrow, William Nierenberg, and some lesser lights—turn up again and again like bad pennies: arguing that tobacco doesn’t cause cancer, that secondhand smoke isn’t dangerous, that acid rain wasn’t real, that the hole on the ozone layer didn’t exist, that climate change isn’t anthropogenic, that nuclear winter wasn’t serious, and that the Strategic Defense Initiative would succeed at defending the US against all of the USSR’s nukes. Something is up here. They clearly aren’t disinterested experts pushing back against politicized groupthink. Public health is not remotely the same skillset as climatology, neither of these has much to do with defense policy, and it is far from clear what expertise physics would give you in any of them.

The correlation between these viewpoints goes beyond These Four Guys Who Won’t Shut Up And Are Wrong About Everything. The authors note that, of the 56 "environmentally skeptical" books published in the 1990s, 92% were published by scholars linked to a think tank or other organization which had received grants from the tobacco company Philip Morris. The tobacco industry front group FOREST took the correlation to its comic extreme. It wrote a report about how secondhand smoke was fake that, in an appendix, included the following examples of ideologically captured science: acid rain, global warming, the hole in the ozone layer, pesticides, asbestos, chlorine, anti-genetic engineering, anti-nuclear, anti-biotechnology, electromagnetic radiation from power lines, heterosexual transmission of AIDS, endangered species, forestry, alcohol being bad for you, and fatty foods being bad for you.1

It’s very easy to jump to the conclusion that there’s some kind of grand corporate conspiracy here: academics who have totally sold out scientific integrity and will write whatever their corporate overlords tell them to in order to earn a buck. It’s not like there’s never a corporate conspiracy. Internal tobacco-company documents show that by the 1960s tobacco industry scientists knew perfectly well that smoking caused cancer and that nicotine was addictive, and by the 1970s they knew that secondhand smoke was carcinogenic. High-level tobacco company executives cynically distorted the science in order to encourage people to buy their products.

But the vast majority of participants—including all of Those Four Guys Who Won’t Shut Up And Are Wrong About Everything—weren’t cynical or corrupt. They were genuinely trying to live out their principles. In the 1990s, Philip Morris funded the ACLU. I don’t think that’s because the ACLU is some tool of the corporate oppressors. The ACLU thought that public-health officials were overplaying how carcinogenic secondhand smoke is in order to justify paternalistic regulation which was actually intended to harass smokers into quitting.2 The 1990s ACLU hated paternalistic legislation that kept people from making their own decisions about their own bodies. Philip Morris donated to the ACLU because the ACLU was already doing things Philip Morris liked for its own reasons.

In the twentieth century, a number of researchers who accepted funding from tobacco companies to study non-tobacco causes of cancer, heart disease, and other illnesses. The tobacco industry funded a lot of good, useful, scientifically valid research into non-tobacco causes of cancer: for example, in 1954, 75 out of 77 medical schools had a fellowship program for researchers studying non-tobacco causes of cancer. Many lives were saved by research funded by the tobacco industry. Perhaps the most tragic case was the prominent pro-tobacco scientist, Wilhelm C. Hueper, a tireless advocate against asbestos; he supported tobacco because he associated “tobacco causes cancer” with asbestos companies trying to get out of paying damages to their victims.

But Those Four Guys Who Won’t Shut Up And Are Wrong About Everything3 weren’t working on their own projects—cancer research or civil liberties—that happened to intersect with all of tobacco, climate change, the hole in the ozone layer, acid rain, and SDI. No, Those Four Guys were idealists.

Seitz and Nierenberg were both members of the Manhattan Project; Singer worked on underwater mine design during World War II, while Jastrow was still in college at the time. Their work during the war left them with a ferocious hatred of totalitarianism. The Guys believed that the mainstream intelligence community completely underestimated the Soviets. While we messed around with mutually assured destruction, the Soviets were stockpiling weapons, inventing defense systems, and preparing to win a nuclear war.4 The only solution was to invent our own defense system, nuke the Soviets first, and eradicate Communism from the earth. Mutually assured destruction, much less nuclear disarmament, smacked of appeasement—and appeasement didn’t work when they were fighting the Nazis.

Those Four Guys believed passionately in science and in free markets. Technology and scientific research had made the United States the richest country that had ever existed. They produced electricity and the smallpox vaccine, antibiotics and fruit out of season. The best way to spread the wealth to everyone was allowing individuals to freely trade with each other, without government interference. Capitalism motivated people to create the new businesses which made everyone rich. And the government meddling in what fully informed people could buy and sell smelled of the totalitarianism they so despised.

The ideas that tobacco caused cancer and that new technologies caused environmental destruction threatened Those Four Guys. If cigarettes cause cancer, it means that science had invented and capitalism had brought to market an enormously destructive product—and “we trust people to make their own decisions about what’s good for them” was insufficient to prevent grave harm. If our power plants caused serious environmental damage, then electricity wasn’t an unmitigated good, but something that caused harm that had to be weighed on the scales. In both cases, the findings might justify government regulation. Those Four Guys suspected that environmentalists and anti-tobacco advocates wanted to return us to a pastoral state of nature without the technology that had so benefited everyone. They also worried—especially given that most scientists were more liberal than the general population—that scientists were misrepresenting the evidence to create an opportunity for the government to intervene, which in turn was the camel’s nose in the tent for Communism.5

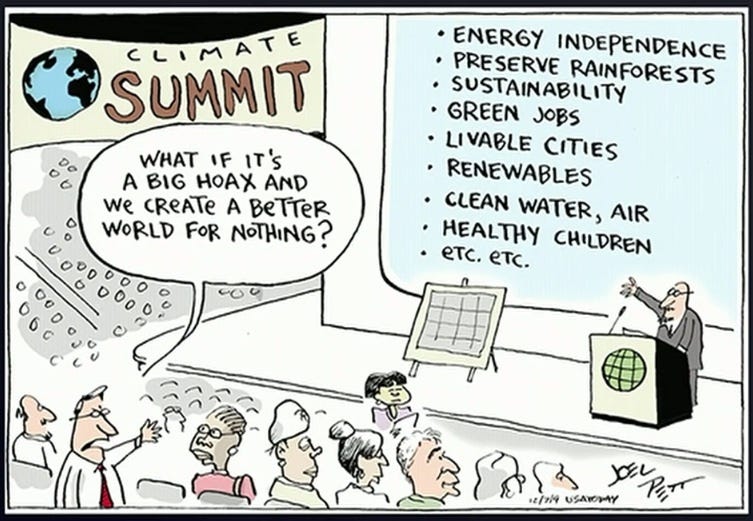

And they weren’t… totally wrong? Like, looking at a comic like this one—

—a reasonable person might conclude that perhaps some environmentalists’ preferred policies are not motivated purely by the desire to reduce emissions of pollutants.

There is a case where Those Four Guys received a negligible amount of corporate money. Far from funding ozone-hole skepticism, DuPont Chemical actively supported research into the ozone hole and voluntarily withdrew CFCs from the market when they were proven harmful. However, several of Those Four Guys still argued that the hole in the ozone layer was overblown. To me, the obvious conclusion is that Those Four Guys genuinely believed they were doing the right thing.

Those Four Guys’s primary tactic was spreading doubt.6

Their favorite mantra was “the science is not settled.” We aren’t sure whether tobacco smoking causes cancer—or whether air pollution is the reason that some samples of rain water are as acidic as lemon juice—or whether climate change is caused by something else, like sunspots. Therefore, we shouldn’t do anything about the situation until we know for sure that something is going wrong.

Spreading uncertainty worked whether or not the uncertainty was material to the question or even actually existed. In the 1950s and 1960s, the tobacco industry incessantly wondered why smoking caused lung cancer but not lip or throat cancer, why cancer rates vary between cities when smoking rates were the same, why some smokers get cancer and others don't, and whether the increase in cancer was caused by longer lifespans and better screening. Some of these were answerable even at the time: smoking isn’t the only thing that causes cancer, so cancer rates vary even if two places have the same number of smokers. Some of these are unrelated to the question at hand: the reasons why some smokers don’t get cancer are interesting, but the thing that actually matters is that smokers are at enormously higher risk of cancer. But you can create an aura of uncertainty, the impression of a controversy, by asking questions—even if the answers are already known or totally irrelevant.

Those Four Guys loved “sound science” and debunking “junk science.” They wanted to maintain high standards for science, and a lot of their criticisms were reasonable, at least prima facie. We shouldn’t draw conclusions from preliminary studies, especially those that overhype their results. We should rely on peer-reviewed studies, not preprints. Animal studies and correlational studies have serious limits. Some studies don’t properly adjust for confounding variables or set p-values that are far too high.

However, we should often take action about problems we’re uncertain about. Those Four Guys reliably assumed that the cost/benefit analysis was always in favor of the status quo—even when it wasn’t. It’s not that costly to society to regulate the pollutants that cause acid rain, and once you do you’ll quickly find out if your theory of acid rain is accurate.

We don’t want to find out how bad nuclear winter is by causing mass famines, or whether acid rain kills fish by driving irreplaceable fish species extinct. Many decisions we make, like putting carbon into the atmosphere, are irreversible. If you are unsure of the effects of your decision, don’t do irreversible things because that’s what you’re already doing. Sometimes, we need to make decisions based on weak or preliminary evidence, because that is the evidence we have available, and the other alternative is catastrophic.

I see similar reasoning used by people who aren’t concerned about existential risk from artificial intelligence. We don’t know how quickly artificial intelligences will improve or how easy it will be to make sure that they do what we want. Therefore—some people argue—we should use artificial intelligences wherever it seems profitable, and we can roll it back if we’re sure that they’re dangerous. No! If some people are saying “hey, I think this technology might kill everybody” and other people are like “but it makes it easier to write emails,” we should not use that technology! The time to tackle the maybe-this-kills-everyone problem is not when the technology touches every sector of our economy!

Spreading uncertainty is easier because the news media tries to be balanced and objective. For much of the twentieth century, under the Fairness Doctrine, TV and radio news stations were legally required to report the news in a “balanced manner,” which they typically interpreted as meaning that they had to give equal airtime to both sides of a controversy. Even today, most news outlets try to report both sides of every issue.

The problem is that it’s easy to make it look like there’s a controversy when there really isn’t. To many reporters, it feels biased and like a betrayal of your duties as a journalist to report that tobacco causes cancer when there are all these people saying that it doesn’t. Trying to figure out which of the groups is telling the truth isn’t your job—you’re a reporter, not an opinion columnist. So the journalist reports “the entire scientific consensus of the public health community” and “three retired physicists who are prolific writers” as if they’re equally credible sources which are equally likely to have uncovered the truth. You only need a couple of intellectually dishonest idealists with impressive resumes to get anything on the air.

A lot of people I know hate Vox for its tendency to write explainers that are really just the center-left opinion on a particular topic. But Vox’s editorial stance is a response to this kind of manufactured controversy. Erring on the side of objectivity means that you devote a lot of page space to beliefs that are flat-out wrong—so you make your readers actively stupider and less informed. Erring on the side of trying to report the facts as you see them winds up collapsing the distinction between a news article and an opinion column. Of course, journalists should report the truth and nothing but the truth—but if you can reliably get people to write articles about complicated topics that only contain true things, you should quit reading this blog post and apply for an Open Philanthropy grant, I think they’d drop a few tens of millions of dollars on you.

Merchants of Doubt suggests some heuristics for people who want to have better understanding of the world. Don’t trust eminent physicists speaking about topics other than physics; the level of credibility people give them is totally out of proportion to the amount they know about the topic. If someone is speaking “as a scientist,” check whether the science they study is at all related to the topic they’re speaking about. If someone speaks “as a scientist” about a dozen unrelated fields—especially politicized ones—that’s a red flag. Don’t assume that “this is uncertain” or “the science isn’t settled” means that we should continue with the status quo—often, uncertainty is a spur to action.

Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway. Published 2011. 368 pages. $10.

If you make your list long enough, eventually you’ll be right about something!

Public health officials were, in fact, totally doing that.

In the interests of space/not boring my readers, I’m treating the Guys as a gestalt entity. For more insight into what parts of this each individual Guy believed, read Merchants of Doubt.

Records from the former USSR show that it had fewer nuclear weapons than the US did and that it always wanted to avoid nuclear war.

To his credit, when pressed to have an actual policy opinion about what to do about acid rain other than “ignore it,” Singer correctly identified that a cap-and-trade system would solve the problem. The policy was implemented and acid rain is no longer a serious concern in the United States. Suspicion of heavy-handed government regulation and a bias towards market solutions are often useful heuristics, if they don’t cause you to misrepresent the evidence.

Except with SDI, which is weird in many ways.

> Don’t assume that “this is uncertain” or “the science isn’t settled” means that we should continue with the status quo—often, uncertainty is a spur to action.

This is something like an "inverse Chesterton's Fence". If someone just built a fence yesterday and it's causing problems, maybe you should tear it down, even if it's not clear why they built it, since they probably also didn't consider why there wasn't a fence in the first place.

> that nuclear winter wasn’t serious

My understanding is that one is true, though! Bean discusses this for instance (among other things) here: https://www.navalgazing.net/Nuclear-Weapon-Destructiveness

> Perhaps the most tragic case was the prominent pro-tobacco scientist, Wilhelm C. Hueper, a tireless advocate against asbestos; he supported tobacco because he associated “tobacco causes cancer” with asbestos companies trying to get out of paying damages to their victims.

I think there's another general lesson here! Like, there can be more than just two possiblities...

> Don’t assume that “this is uncertain” or “the science isn’t settled” means that we should continue with the status quo—often, uncertainty is a spur to action.

Thank you for making this explicit!