[content note: emotional abuse via suicide threats and harm to animals]

Christabel Russell was born in 1895. The child of a middle-class British family, she grew up a bohemian. She spent her adolescence in Paris, where she was never chaperoned and where she took life-drawing lessons (not an acceptable occupation for a respectable daughter of the middle classes.)

Christabel was beautiful, graceful, charismatic, and outgoing. As a true modern woman, she hunted, played tennis, danced at dance halls, flirted with men, and drove both a car and a motorcycle. She wore only dresses of her own design. She was notoriously honest; her friends and family said that she simply could not tell lies. This is important, because we rely on her testimony for much of the absolutely wild stuff that is to come.

During World War I, Christabel Russell was a successful businesswoman, working first as a manager of 2000 female munitions workers, then as a buyer for an armaments company.

Much to Christabel’s great irritation, men kept pestering her with marriage proposals. So she married John Russell, the future Baron Ampthill, in order to drive them off. John’s parents were horrified that he’d married beneath him—they had hoped he’d marry a royal—and didn’t attend the wedding.

Christabel intended to allow marriage to disrupt her life as little as possible. She slept in a different bedroom from her husband. She went out every evening with other men, usually to dance. She made no effort to hide her flirtations from her husband (pg. 181-182):

For example, she wrote to him from Switzerland, where in January 1920 she had gone on a long holiday with her mother, but without her husband, to recover from pleurisy: ‘your wife has a vast following of adoring young men … several of the type after my very own heart. Dark, sleek Argentines and Greeks who dance like dreams of perfection.’ (These would have been paid dance partners, the male equivalent of Freda Kempton.)1 She writes of one in particular: ‘I am so in love with my Dago young man! … He looks very ill and his hair is beautifully marcel-waved … Can’t I just see my husband of mine shuddering at the thought … Your very naughty wife’. In another letter she asked: ‘You don’t mind wife having the most awful amount of young men, do you? … You take them so seriously and are not able to realise like mother that they make about as lasting an impression on me as ice-cream in hell.’

In another letter she wrote “I have been so frightfully indiscreet all my life that he [John] has enough evidence to divorce me about once a week.”

Continuing to ignore expectations for what married women were supposed to do, Christabel Russell founded her own fashionable dress shop, where she designed most of the dresses. It was a wild success, and she was known as an extraordinarily hard worker.

John Russell was… kind of… a trans woman? I know that we can’t say anything about the identities of historical figures. But when he lived at home, he regularly dressed up in his mother’s clothing. Once he had his own place, he kept an entire wardrobe of women’s clothes, which he wore regularly for fun. He even went to a friend’s apartment and passed himself off to visitors as one of her female relatives. Like I said, we can’t know for certain what his identity would have been if he were exposed to 21st century notions of gender, but the evidence does sort of waggle its eyebrows and point in a direction.

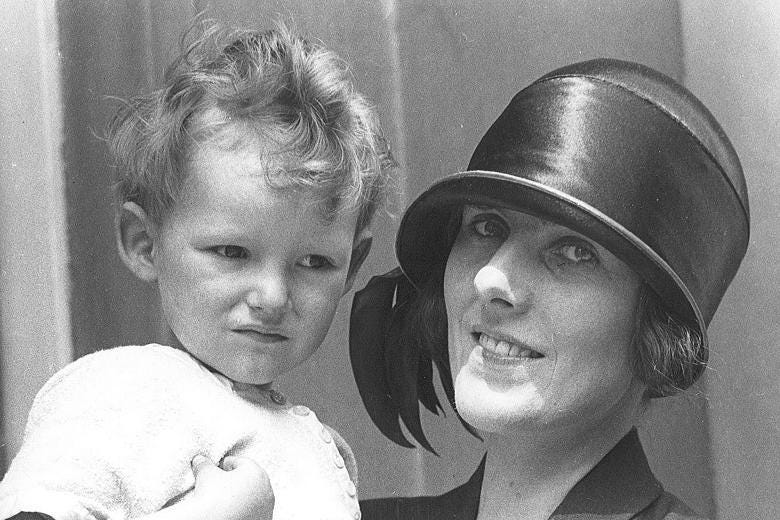

In 1921, Christabel Russell visited a clairvoyant, as was her habit. The clairvoyant sensed “the vibrations of the hormones” and told her she was five months pregnant. Christabel, perhaps wisely, sought a second opinion from a doctor and discovered it was true—she was, in fact, pregnant.

John Russell immediately sued for divorce on the grounds of adultery as, you see, he could not possibly have gotten her pregnant. By the time of the first trial in 1922, baby Geoffrey had already been born.

We know the gory details of the Russells’ sex life from the series of two court cases and two appeals that followed.

Christabel had asked that they delay having children. John had given her a copy of Modern Love, the first book about birth control, but she had refused to take birth control. They practiced “partial intercourse”: that is, John put in just the tip of his penis, without fully penetrating her. Much to the shock and confusion of both John Russell and frat boys, just-the-tip can in fact get you pregnant.

Medical examinations showed that, in spite of her pregnancy, Christabel’s hymen was unbroken. Christabel’s lawyers argued that this meant she hadn’t taken a penis fully inside her, so she’d gotten pregnant from just-the-tip. John’s lawyers argued that there was no reason to assume that she hadn’t done just-the-tip with other men, and anyway she was notoriously extremely flirtatious.

Christabel and John had an extremely concerning marriage. John Russell usually asked for sex by threatening to commit suicide unless she had sex with him, and once by threatening to shoot her cat; he would lie in bed with a shotgun balanced on his feet and his toe on the trigger and threaten to shoot himself if she didn’t have sex with him. Christabel, for her part, said in the court case that it disgusted her that her husband hadn’t insisted on penetrating her fully (even though she didn’t want children) and that she didn’t admire him because he had never threatened to shake or beat her.

Christabel said that all sexual subjects disgusted her, she had no interest in them, and she didn’t want sex with men. A revealing set of quotes from the cross-examination (CR is Christabel Russell, MH is John Russell’s lawyer, pg. 193):

MH: Did you notice what is the main difference between a man and a woman on that night when he was in bed with you? [their wedding night]

CR: How should I?

MH: Do you mean to tell us that you did not know whether your husband was differently made?

CR: That is a most ridiculous question. I have been an art student in Paris, and I have studied anatomy from the age of 12 …

MH: So you had seen a nude man?

CR: Constantly …

MH: Have you never had the smallest curiosity to know what that portion of the man’s body was intended by nature for?

CR: I had not the smallest curiosity.

MH: Do you know that in moments of passion that portion of the man’s body gets large?

CR: I did not know that.

MH: Do you know that now?

CR: You have told me.

MH: Never mind about my telling you …

CR: No, I did not know until you have just told me …

MH: During this partial intercourse, when you say that your husband had emissions, do you say that that you did not realise that his person became rigid

CR: No, I did not.

MH: Has he ever had this partial intercourse with you that you suggested?

CR: He has told you so.

MH: And yet you noticed no difference?

CR: No difference in what?

MH: Between the person in quiescence and the person in excitement. I use the word ‘person’; you know what I mean?

CR: This is – Oh! … …

MH: Did you know the object for which he wanted to put his person inside yours?

CR: It seemed to be objectless; it seemed to have no object. I could see no satisfaction from it.

It’s kind of difficult to figure out to what extent Christabel was shockingly sexually ignorant and to what extent everyone beating around the bush made it impossible for her to figure out what they were trying to say.

By all accounts, Christabel had had minor pregnancy symptoms which were easy to miss. She had also once missed her period for an entire year, even though she was not sexually active. At the time, it was not considered especially surprising for a woman to miss that she was pregnant for five months: after all, sometimes people’s periods stop for no reason, and there were no pregnancy tests. A doctor testified about a nurse of his who believed she had an ovarian tumor but, on examination, was discovered to be pregnant with twins and about to go into labor.

The delicacy of everyone involved about sexual matters is striking. A lawyer characterized periods as “this unpleasant subject which is always unpleasant to men.” The author writes (pg 199-200):

One example of such [delicacy] can be found in [the newspaper’s] account of Christabel’s cross-examination:

"Questions were asked [by Sir Edward] which would have embarrassed a woman alone with her physician … She said she did not understand … he repeated the question … she answered again that she did not know what he meant. ‘Then I am very sorry to have to explain,’ he said quietly. He did so. No newspaper could possibly repeat his words."

The transcripts however do allow us to repeat his words. When Christabel indicated that she was unclear of the difference between being examined ‘visually’ or ‘digitally’ by a doctor, Marshall Hall responded: ‘Well, I will tell you; I am sorry I must tell you. Digitally is by putting his fingers into your private parts to examine in that way; visually is by looking to see your private parts.’ She sensibly replied: ‘One could not do one without the other, I should imagine.’ The exchange was in fact possibly rather less obscene than anything the reader had been encouraged to imagine.

In 1924, on the second appeal, the House of Lords ruled all evidence related to the child being born out of wedlock was inadmissible, due to an 1869 law forbidding a couple “to bastardise any issue of their marriage.” As such, the Russells had to stay married. A prisoner wrote Christabel a letter proposing marriage to her as soon as he got out, reassuring her that he would raise her son right; she did not take him up on it.

In 1925, Christabel wrote and starred in a movie, Afraid of Love, based on her experiences. A review characterized it as (pg. 201):

An indifferent production of a dull and disjointed story of the penny novelette type … Of the Hon Mrs John Russell one can say only that she walks through the part of Rosamund with more apparent concern for the many elaborate gowns than for the emotional demands of the character. To be candid, her performance is that of an untrained and unpromising amateur.

The newspapers covered the Russell trial avidly, as it combined their two favorite things:

Salacious and titillating stories about weird sex

Moral outrage about people having weird sex

The king himself complained that the papers were talking too much about sex, that it was harming the sanctity of marriage, and that all this was going to corrupt the impressionable working classes. In 1926, in part because of the Russell case, a law was passed banning detailed reporting on divorce cases.

In 1935, John Russell’s father died, and Christabel became Lady Ampthill. She immediately petitioned for divorce, and the couple actually divorced in 1937. She never remarried and had no more children.

Upon John Russell’s death in 1973, Geoffrey Russell became Lord Ampthill. John Russell’s son with his second wife, John junior, sued to become Lord Ampthill. Geoffrey refused to get a DNA test. The House of Lords ruled that Geoffrey was the lawful heir, because it had been decided in court years ago and the House of Lords had no power to overturn it. Geoffrey Russell proceeded to have an uneventful life as a crossbencher in the House of Lords.

Christabel ran her dress shop, worked as a costume designer for British films, and eventually moved to a castle in Ireland, where she hunted foxes seven days a week and became friends with a young Anjelica Houston. Christabel died at age eighty, having spent the last few years of her life traveling the "hippy trail" on buses throughout Southern Asia. She died shortly before the House of Lords ruled that her son Geoffrey Russell would inherit the title.

Modern Women on Trial: Sexual Transgression in the Age of the Flapper, by Lucy Bland. Published 2013. 256 pages. $23.

Ozy’s footnote: Paid dance partners do dance with people, but are mostly paid to flirt with rich people. Some were sex workers. Freda Kampton was a paid dance partner who died young of a drug overdose, and was discussed earlier in the book.

For anyone who gets the same curiosity about a potential family connection as I did, and to spare them the British-peerage rabbit hole I dived into to satisfy it: John Russell was Bertrand Russell's second cousin once removed. To be precise, John's great-grandfather and Bertrand's grandfather were siblings.

John Russell was, himself, merely the son and heir of a baron, but he was from the very prominent Russell family. His great-uncle Francis Russell was the 9th Duke of Bedford, while his great-great-uncle, John Russell was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice and the 1st Earl Russell. The 3rd Earl Russell (the first earl's grandson) was Bertrand Russell, the noted philosopher and mathematician. He would be our John Russell's "second cousin, once removed".

The son of a baron would be thought rather lowly to marry royalty, but a member of an ancient and important family like the Russells is a different story altogether.