Weird People of History: Jenny from the Jane Abortion Collective

Direct action when abortion was illegal

Jenny (we know her only by her pseudonym) was one of the leaders of the feminist Jane Collective, a Chicago group which helped women access illegal abortions from 1968 to 1973. My source for this post is The Story of Jane, an excellent history written by a Jane member and drawing on interviews with many other participants.

Jenny was radicalized about abortion when she was twenty-six. She was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma when pregnant with her second child. She had to delay treatment a crucial three months to protect her fetus. After she gave birth, she wasn’t expected to live for very much longer, a few years at most; she would have to undergo regular chemotherapy, which would cause severe disabilities in any fetus. Doctors still refused to sterilize her after she gave birth, saying that she was too young to know if she would want to get pregnant in the future.

At that point, the birth control pill wasn’t as effective as it is today, and Jenny got pregnant a second time. The doctor didn’t believe her that she was pregnant again, but concluded that she was so hysterical about pregnancy he would have to schedule a tubal ligation. Much to the doctor’s surprise, she turned out to be eight weeks pregnant.

Jenny couldn’t delay treatment for her lymphoma any longer, so her baby would be born with severe disabilities. She begged for an abortion. At the time, Jenny legally wouldn’t be able to get an abortion unless her life was in danger, and she could get chemotherapy while pregnant, so it wasn’t. She convinced two psychiatrists that she would commit suicide unless she had an abortion, and managed to have the procedure.

Shortly thereafter, Jenny went to a meeting of a voter’s group she volunteered with and met Heather Booth. Heather was a feminist speaker, so people knew who she was and assumed that she would be able to get them an abortion. She had started to refer women to abortionists she knew and trusted. Unfortunately, there was far more demand for abortions than Heather could keep up with, so she decided to found a group to take over. This group would counsel women about abortions, explain the process to them, and refer women to get abortions from screened doctors whom they trusted not to kill women. Heather invited Jenny to the first meeting.

Heather viewed the Jane Collective as a consciousness-raising group. Before she would tell any of the members the names of the doctors she referred them to, she would have to be satisfied that they had impeccable feminist politics and understood abortion’s precise role in women’s liberation. Jenny found this frustrating. She was an action-oriented woman: she just wanted to go go go. She didn’t want to sit and talk about what abortion criminalization showed about society’s attitude towards women: she wanted to get women abortions! Jenny even briefly quit the group to volunteer with the Black Panthers, but returned upon getting fed up with the Black Panthers’ sexism.

Eventually, Heather allowed them to transition to talking about logistics: how to counsel women, how to arrange for an abortion, how to screen doctors, how to handle emergencies, how to protect themselves from prosecution. Jenny still found this frustrating; she felt like they could figure it out as they went, from experience. The group was named when Jenny commented, after one lengthy meeting, that it felt like they were creating a monster. Another woman said that she “like[d] [her] monsters to have sweet names, like Fluffy or Jane.” Jane it was.1

After the six months were over, Jane had shrunk to four women. This would be Jane’s smallest size. In general, it was made up of a few dozen women, growing when they sought out new recruits, shrinking in the wake of dramatic events or because of burnout.

Jenny and another woman called Miriam were in charge of contacting the doctors. They both would also counsel women about abortions. Counseling sessions covered a range of issues, depending on the individual woman: education about abortion;2 education about birth control;3 screening women for coercion into an abortion; helping women decide whether they wanted to abort; feminist consciousness-raising; and, very often, brainstorming how to raise the money.

In principle, decisions at Jane were made by consensus of all members. In practice, consensus was impossible. Because Jane was illegal, much information was need-to-know. Consensus was also a very slow process, and many decisions needed to be made quickly. And Jenny and Miriam worried that, if the group disagreed or had political arguments, the work would suffer and Jane would fall apart.

Jenny and Miriam made most decisions themselves, then presented them to the group for ratification. As Jane grew bigger, Jenny and Miriam started to consult their inner circle of two to four women—women they chose fairly arbitrarily based on who lived near to them and whom they liked. Weekly group meetings usually just involved women picking their jobs for the week. One member said to the historian, “we pretended we operated by consensus but that’s because we never talked about anything.”

Women who just counseled tended not to care, but women who were heavily involved and not in the inner circle felt resentful. Issues would be blown out of proportion because they became referendums on Jenny and Miriam’s leadership—which only cemented Jenny and Miriam’s feeling that the main group shouldn’t be involved in decision-making.

The average abortion was $600, which is about $5,300 in today’s money. The women who sought out Jane—often poor, teenagers, or black—often couldn’t come up with the cash. One woman even sold sex in order to get money for an abortion. Occasionally a doctor would throw in a free abortion, allowing Jane to lower the price. Jane offered interest-free loans for women who couldn’t pay, but had no way of making women pay them back. Their loan fund was perpetually low on cash.

Finally, Jenny decided to play hardball. She found a reliable doctor, Dr. Kaufman, and agreed to refer him ten abortions a week, as long as he only charged $500 per abortion (about $4,400) and let Jane know where the clients were. At this point, Jane was nowhere near referring ten abortions a week, but Jenny thought they could figure something out. Indeed, between pamphlets handed out at women’s groups, signs telling women to call Jane, and referrals from doctors and clergy organizations, they more than reached Dr. Kaufman’s requirements.

Speaking of women’s groups—

A vocal contingent believed the [Chicago Women's Liberation Union] had to have a radical focus, i.e., to address the roots of the problems that women faced. Rather than reform the existing oppressive system, they should promote sweeping changes that would profoundly alter society. Abortion counseling, they argued, was not a radical activity but merely reformist social service work. How could an illegal, underground, service organization that referred women to male abortionists and charged hundreds of dollars, be considered radical? Jane was a Band-Aid that might help a few women but did not further or reflect the social changes they envisioned. Since abortions were so expensive, and therefore limited to women who could come up with money, how did this service meet the needs of poor people and black people, who were the most oppressed? How could this service fulfill the union’s mission to bring large numbers of women into their movement and train legions of organizers?

Nothing ever changes and everything is always the same.

Nevertheless, Dr. Kaufman was a bit of a flake, once disappearing off the face of the planet for several months. So Jenny had to keep track of numerous backup doctors: how much they cost; whether they were getting nervous about the police; whether they should be blacklisted for incompetence or for predatory behavior. At one point, Jane had to blacklist a doctor for showing women a bag full of the fetal parts and saying "look what you've done.” Another doctor was blacklisted for charging white women twice what he charged black women.

Dr. Kaufman had a middleman, Nick, who mysteriously had to fly in whenever Dr. Kaufman had to do abortions. Jenny never spoke to Dr. Kaufman himself, even on the phone; all inquiries went through Nick. Then Dr. Kaufman got attacked by an angry husband yelling about how he was a baby killer. He called Jenny to rescue him and who was there but Nick! Nick attempted to claim that the doctor wasn’t there because he’d kept running, but Jenny called bullshit: she knew he was Dr. Kaufman in a paper-thin disguise.

Now that Jenny knew that Dr. Kaufman was Nick, she could pressure him into letting someone from Jane observe the procedure so that he couldn't mistreat his patients. He also had no one to deflect to when she berated him about the high price of his abortions. Women were in need. Abortions weren’t a luxury; they were a necessity. How could he justify charging so much? She pushed him into performing free abortion after free abortion. When he stood up to her, she just switched tactics and asked for a discount. To mollify her, he sometimes went as low as $25 (about $220).

After about six months of watching Nick perform abortions, Jenny concluded that abortions didn’t seem hard. She began a campaign to get Nick to teach her to perform abortions. Worn down by the force of her personality, Nick began to teach her, starting with having her hand him instruments. Eventually he laid off his nurse and had her act as his nurse. At the same time, and with her usual attitude towards the concept of “group consensus,” Jenny repeatedly asked the group to approve of Jane members learning to perform abortions. The group consistently said that they were already overwhelmed, and anyway only doctors could perform abortions."

(It is important to remember, when all this is going on, that Jenny still had Hodgkin lymphoma and was receiving chemotherapy.)

Unfortunately, a woman who was about to get an abortion from Jane was arrested for seeking an illegal abortion. Making an excuse that she needed to call her son, the woman called her counselor to say that the police were coming. Jenny, Nick, and the rest of the staff frantically cleaned the apartment and managed to get all the medical supplies out the back door before the police arrived.

This showed the Jane Collective that the current course of action was unsafe. Jane decided to use two apartments: the Front and the Place. Women would gather at the Front as a waiting room; then one at a time they were driven to the Place to have an abortion. The idea was that police would raid the Front, giving them some crucial warning that would allow them to clear out the Place. Jenny pressured her friends to let her use their apartments as the Front and the Place. This was not an ideal setup, because one of the only Places Jenny could find belonged to a Maoist revolutionary under constant surveillance by the FBI. But Jane was kind of desperate. None of Jenny’s friends whose apartments Jane used were Jane members. This further exacerbated divisions in the group: only Jenny had all the information to make decisions about where Fronts and Places should be.

And then Miriam learned that Nick wasn’t a doctor. He had been apprenticed to a doctor to learn to perform abortions, but he had no medical license. Jenny and Miriam decided that all Jane members had to learn that Nick wasn’t a real doctor: it was unethical to let them refer patients to Nick under false pretenses.4 Jane members were shocked. They felt like they had been lied to and that they were lying to women. Some even proposed shutting down the service. According to some Jane members (memories disagree), half the group left in the wake of the revelations.

The remainder, however, realized that Jenny had been right. If Nick could perform abortions safely and effectively, without being a doctor, then they could too.

At this point, which was early 1971, Jane was doing twenty abortions a week. Nick did nothing but the actual abortion itself: the rest was handled by Jane volunteers in order to maximize throughput. Jenny negotiated for Nick to have a per diem of $300 ($2,600 in today’s money): he was performing ten abortions per day for half what he used to charge for a single abortion. They no longer had to turn down women for lack of funds, although sometimes they failed to make Nick’s per diem.

In spring of 1971, Jenny performed her first abortion: an emergency D&C because an induced miscarriage (which they did for late-term abortions) went wrong. She presented this to the group as a fait accompli. Many women left: even if they tolerated a man who wasn’t a doctor performing abortions, it was quite another thing to tolerate a Jane member herself performing abortions.

By the summer of 1971, Nick performed fewer than half of Jane's abortions. Jenny was fully trained and two more women were close to trained. Jenny got Nick to lower his per diem since he was doing less work. Now, Jane charged $100 ($775) per abortion, with the average woman paying $50 ($339) per abortion. Women only paid what they could afford. Some women paid in installments. Some paid as little as $7 ($54). In spite of this, Jane now had enough money to pay a small salary to Jenny, her abortion assistants, and the women who received Jane phone calls and called women back.

Jane now primarily served poor women of color; it was usually the only feminist service these women encountered. Jane was mostly white, and they had no way of recruiting members of color: their clients were too busy; the feminist movement was overwhelmingly white; black radicals viewed feminism as antiblack subversion and anyway were under FBI supervision. Jane was mostly middle-class because only middle-class women had the free time to do the work. Still, Jane’s clients weren’t inclined to write callout posts; they were mostly grateful to have a safe, affordable abortion option.

Jenny was growing sicker with Hodgkin lymphoma. As the group's only non-Nick abortionist, she couldn't quit, but she was too sick to do much else. Jenny stopped attending meetings. She would make decisions with Miriam and then leave Miriam to tell the group—making her unilateral decisions increasingly hard to challenge.

By the end of 1971, Jane ended its relationship with Nick. It was now performing sixty to seventy abortions a week. Because of the difficulties arranging for Fronts and Places, Jane only had two work days a week, which put a tremendous strain on the abortionists. Jenny herself performed most of the abortions, sometimes as many as thirty abortions a day.

Jane members often withdrew from people who weren't Jane members. Jane members were afraid to talk about committing crimes with people who might turn them in. And people who weren’t Jane members were horrified by the stories and even more so by all the black humor.

All this was compounded for the abortionists, who always had too much work and too little time. One abortionist had to drop out of grad school because she couldn’t handle it alongside Jane. But the stress was particularly bad for Jenny. Jenny contracted hepatitis and never recovered, alongside her Hodgkin lymphoma. Her workload only went up. She was irritable and blew up at everyone. Even minor inconveniences would make her scream. An assistant once caught her crying into a sink.

Jane members often saw Jenny as power-tripping: she was keeping the knowledge of how to perform abortions to herself so she could have more say in how Jane was run. Her irritability didn’t help. But Jenny was just overwhelmed. She was tired and wanted to stop doing abortions. But training new abortionists meant that her work day would go on even longer, and she was just exhausted.

Jenny finally wound up checking herself into a psychiatric ward, because she felt it was the only way she could get a break from performing abortions.

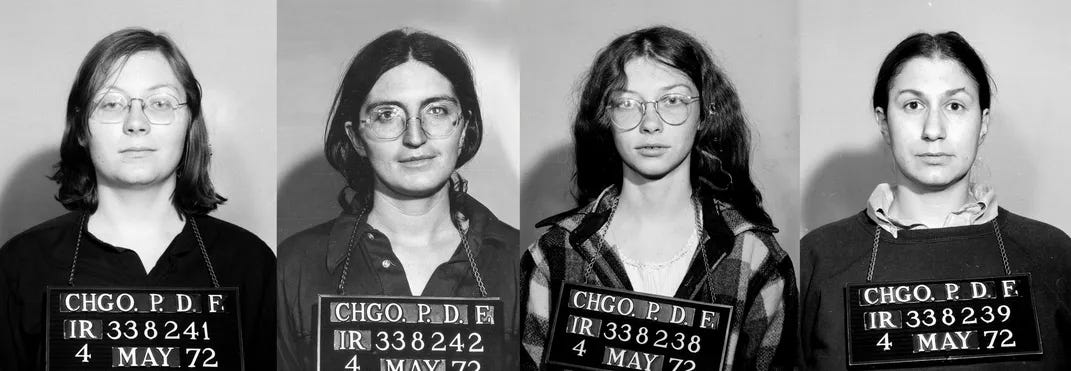

On May 3, 1972, homicide detectives raided the Place. All seven Jane members on duty were arrested. One member was carrying the index cards with the names of each woman who had contacted Jane; the Jane members ate the cards in the back of the police van so the police couldn't harass their clients. The police were baffled by the group of people they'd arrested, repeatedly asking "where's the man?"

Miriam, the one member of Jane's leadership that was neither in jail nor in a psychiatric hospital, sprang into action. Within a few hours, she collected $10,000 ($75,600) for the women’s defense. Miriam contacted the two women on duty to call potential clients to tell them what was happening. Those women called back Jane’s entire backlog of 250 women. They told the clients who could afford it to go to New York. The ones that couldn’t? Jane promised to call back in a week.

Jenny checked herself out of the mental hospital. She and Miriam called an emergency meeting. Some women-- including some of the arrestees-- argued for lying low for now.

Jenny exploded, “But there are all these women who need abortions. What will happen to them?” It struck Gail that Jenny said it as if she could see an endless line of desperate women stretching before her.

Jenny announced that Jane would keep going and anyone who felt it was too risky should leave. The seven arrested women felt unsupported: first everyone was too worried about getting arrested themselves to comfort or praise them, and then they got kicked out of Jane because Jenny wanted to keep the group going.

But Jenny and Miriam did pull it together for their clients. Miriam arranged for free abortions for any women who could get to New York or D.C. Jenny and another abortionist managed to perform ten abortions a week. Together, they ensured that every woman who came to Jane for an abortion got one.

Because of the enormous shortage of abortionists, Jane scrapped the de facto "if an abortionist likes you, they'll train you as an abortionist" policy. They started training all Jane members to do abortions.

The raid turned out to be a fluke. Someone's sister-in-law was mad about the abortion, and the person who normally quashed investigations into Jane wasn't on duty that day. Two of the three clients that the police found refused to testify against Jane. The prosecutor was too embarrassed to say the word "abortion" so he said "did any of these people touch you in the vicinity of the vaginal area?"

Still, Jenny was burned out. She had multiple chronic illnesses and two children, and was working long hours for little pay.

One day in August, she had a client with a low pain tolerance so the abortion had to stop every few minutes. Her next client was a teenager who said she was eight weeks pregnant but turned out to be four months pregnant, which meant that instead of a simple D&C they would have to do a dangerous and complicated induced miscarriage.

Jenny prayed: Let me get through this one, please. She knew that was the last abortion she could do. “I couldn’t stand to watch the suffering anymore,” she says, “of this endless line of women stretching into infinity who got pregnant because they got fucked at the wrong time of the month. It was just too much. I couldn’t do it anymore.”

When she got off work, Jenny begged the arrestees to return to Jane; she couldn’t keep going, but she didn’t want to fail the women. Three arrested women rejoined the service and went back to performing abortions, and Jenny retired for good.

Jane ended shortly after Jenny’s retirement. On January 2, 1973, the Supreme Court decided in Roe v. Wade that women had a protected right to an abortion. Jane closed down for good in March. In the same month, the charges against the arrested women were dropped.

Jenny survived Hodgkin lymphoma and hepatitis, and lived at least until 1995, when The Story of Jane was written. She was a loving mother to her two daughters, with whom she stayed close when they become adults. She became a professional dog groomer, but still did political activism on the side. She, like most Jane members, spoke rarely about her experience.

Over the course of five years, Jane helped with over 11,000 abortions.

Jane acquired a surname, Howe, because she told women How to have an abortion.

Many women were very ignorant about abortions. For example, they didn’t realize that it was a simple procedure with a low complication rate if done properly.

All clients received a free pamphlet explaining birth control.

Nick was unhappy about this but had long since learned that he almost never got his way with Jenny.

I love stories like these. A lot of tales of oddballs getting tired of "normal" activism and striking out to solve the problem themselves end in martyrdom when their plans fail and the law gets them and their memories get used more for their inspirational/dramatic cultural value rather than as an example of true success. Not Jenny and the rest of Jane though, they provided medical help to over ten thousand people in a time and place where few others did.

I’m confused by the chronology in the first few paragraphs. She got pregnant and then gave birth and then found out she was eight weeks pregnant when the doctor tried to have her tube tied? How would they sterilize her while pregnant? These are two different pregnancies?