When I first considered doing life coaching, a therapist friend suggested I look into solution-focused brief therapy.1 I read about it and really liked it. I also discovered that many of the techniques hadn’t seeped into the water supply yet. So I figured I would write up a post with the points I found most insightful, so that people could read it and apply it to their own problems and put me out of a job.

Think About What You’re Good At

When we’re trying to solve problems, there’s a natural tendency to focus on, well, the problem. After all, that’s what you’re worried about!

But often the solution to your problem comes from your strengths. If you’re good at something, you’re much more likely to be able to use it to resolve a problem than if you suck at it.

So when you’re trying to solve a problem, ask yourself what you’re good at, what you like doing, and how you learned those things. Brainstorm ideas, even if they don’t seem very related to the problem at hand. Be sure to list off both specific skills and personality traits.

Then look through your list and see if there’s something you can use creatively to resolve your problem. For example, if you’re a fun person who’s always up for a game, maybe you can try playing a game with your kid to get her to brush her teeth. (Both pretend to be robots! Brush your hair with the toothbrush and make her tell you how to brush your teeth properly!) Conversely, if you know you’re a strong-willed person who doesn’t give in to tantrums, you can strictly enforce that no storytime will happen until teeth are brushed.

Similarly, if you can’t find a romantic partner and you’re a good artist, maybe you could sell paintings at an art show and meet people there. On the other hand, if you are witty and have good takes, maybe you could slide into people’s DMs on X. If you have no merits other than sheer bloody-minded determination, maybe you can approach strangers on the street until you find one that wants to go out with you.

Sometimes you might be mystified about what talents you have. If that’s the case, try thinking about what talents other people might say you have: your friends, your boss, your coworkers, your teachers (present or past). You might also try going through specific areas of your life. What subjects were you good at at school? What skills do you use at your job? What hobbies do you have, and what good traits do they show? Is there anything you accomplished in the past that you’re proud of? Have you made any self-improvements that you’re really happy about?

Think About When The Problem Doesn’t Happen

Almost no problem happens literally 100% of the time. If you have insomnia, sometimes you manage to sleep through the night. If your kid throws tantrums, sometimes you have a fun and pleasant afternoon together. If you keep fighting with your girlfriend, sometimes you ask her for something and she says “not now, but I’ll do it in a couple hours?” and no one screams at each other even a little bit. If you’re miserable all the time, sometimes you manage to feel a moment (however fleeting) of joy.

Even some problems that seem like they happen 100% of the time have exceptions. For example, most people who are single have had a romantic partner at some point. Most unemployed people have had a job at some point. Even people who are always sick have some days that are better (even a little bit).

Therefore, from a certain perspective, you have already solved your problem. The difficulty is figuring out how to solve it consistently.

This should give you some hope. It isn’t an impossible situation. You have already made some progress before you even started.

The key question to ask yourself: what’s different when the problem doesn’t happen?

Maybe you sleep through the night when your room is a nice temperature, or when you haven’t been too stressed at work, or when you’re absolutely exhausted.2 Maybe your kid is fun to interact with when she has a big lunch, or you went to the park together and got her wiggles out, or you aren’t rushing out the door. Maybe you and your girlfriend can resolve conflicts easily when she’s not too busy, or when you’ve thanked her for the stuff she’s already done for you. Maybe you feel joy when you go for a walk or drink a cup of tea or play a favorite video game.

You might not know right away what the difference is, especially if you aren’t an especially observant or self-aware person. It can help to keep a journal where you track when the problem could happen but doesn’t.

Once you know what causes the problem not to happen, you have some strong candidates for what to change to keep it from happening the rest of the time.

Think Concretely About What A Solution Would Look Like

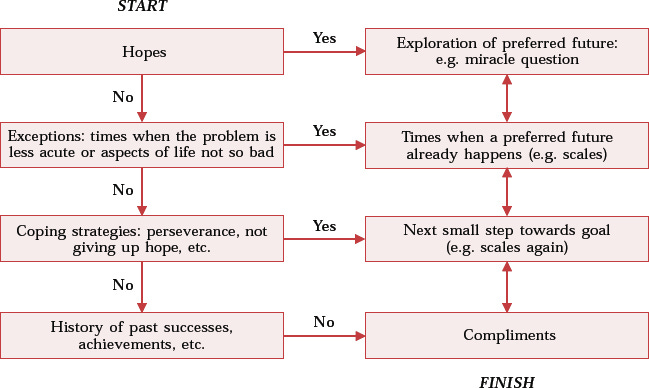

The miracle question, in solution-focused brief therapy, goes something like this:

One night, a fairy stopped by and waved a magic wand and solved your problem. But because you’re asleep, you didn’t know that this happened. What would be the first thing you’d notice that would let you know that your problem was solved?

People always answer this with “I’ll have ten million dollars” or “my chronic fatigue would be cured” or “I won’t be depressed anymore.” But you wouldn’t be able to notice any of those things as soon as you wake up.3 What would you see?

Maybe you’d wake up and see the sleeping face of someone you love very much. Maybe your kids would get out of bed on their own and dress themselves and make themselves breakfast. Maybe you’d feel well-rested and energetic. Maybe you’d look forward to seeing a concert in the evening. Maybe your room would be neat and tidy, with furniture you love and pictures on the wall and three houseplants.

Now, several of these you might need a fairy’s help with: you can’t Simply Just fall in love with someone who loves you back, or feel well-rested every morning. But several of these are completely possible without magic. You can in fact keep your room clean or get your children to make their own breakfast—even without the intervention of helpful fairies. And buying concert tickets or wall art is trivial.

Continue over the course of your day, thinking in very concrete detail about what you’d notice if your problem was solved. How would your commute go? What would your work be like? What would you have for lunch or dinner? What would your evening plans be? What time would you go to sleep? What about the weekend—what would you do then?

By the time this exercise is done, you’ll have a list of concrete improvements. Some of them will be nearly impossible. Some of them will be doable with hard work and a bit of creativity. And some of them you can just do right now in your ordinary life, and it isn’t even that hard.

Why is the miracle question effective?

First, people who seem to have the same problem may want very different things.

Three people might all want to “get fit,” but one might want to be more sexually attractive, one might want to be able to carry her toddler, and one might want to feel strong and energetic in everyday life.

Three people might all want to “be less lonely,” but one wants to host events twice a week, one wants a girlfriend who loves her, and one wants someone who is willing to talk to her about her favorite TV shows.

Three people might all want to “stop being depressed,” but one wants to go out to exciting events and have a wide circle of friends, one wants to sit at home reading a book, and one wants to learn a variety of obsolete skills like artisanal cheesemaking.

Three people might all want to “be more successful,” but one wants to save enough money that she isn’t worried about losing her job, one wants her father to approve of her, and one wants to make a groundbreaking scientific discovery.

These are different goals, which suggest different plans. A fitness plan designed to help you carry your toddler might not be ideal for being sexually attractive. No amount of wild parties will cure your depression if your soul cries out for artisanal cheese. And sometimes the solution isn’t even related to the apparent problem: maybe, instead of trying to reach your father’s standards, you need to have a hard conversation with him about how you’re happy just the way you are and he needs to accept that.

Second, many people tend to fall into all-or-nothing thinking. Either we have a perfect solution to our problems right now—with the ten million dollars and the chronic fatigue cure and the soulmate and the kids straight out of a Hallmark movie—or nothing can ever get better even a little bit. By making the solution concrete and discrete, the miracle question lets you see what parts of a solution you can have. By beginning with the easiest parts of the solution, we can gradually work our way to the parts of the solution that seem difficult, or even like they might require magic.

Third, quite often people respond to the miracle question by going “I have no idea what a solution to my problem would look like.” I think this is particularly common for depressed people: you know that you want to stop hurting, but you don’t know what “not hurting” would look like. But if you don’t know what you want, you can’t get it. You now know what you need to work on.

Solutions Aren’t Necessarily Related To Problems

Consider the following situations:

Your wife dies, so you feel sad and lonely. You take up gardening, which distracts you, gives you pleasure, and brings you into a community of fellow gardeners. You still grieve your wife, but you no longer dread waking up in the morning.

You were parentified as a child, which means you feel worthless unless you’re taking care of someone. You become a nurse and work long hours taking care of patients, which gives you a sense of satisfaction and self-esteem.

You struggle to find a romantic partner. You build strong and supportive friendships, regularly babysit your friends’ kids, and snuggle your pet dog when you feel touch-starved. You still idly wish you had a partner, but you feel happy.

Does gardening solve the problem of your wife’s death? Does being a nurse fix your parentification? Are good friendships basically a kind of romance? No, no, and no.

Some people say that the solution has to be related to the problem. As long as your childhood trauma is unresolved and you don’t have a girlfriend, you’ll feel some deep dissatisfaction, a fundamental kind of emptiness, that only going to the root of your problem can resolve.

This belief is a conspiracy by Big Therapy to sell more therapy.

To be sure, solutions are sometimes related to problems. I’m not sitting here going “no one ever works through their childhood trauma and it is impossible to solve your romantic loneliness by getting a girlfriend.” And I’m not saying that you have to settle for inadequate solutions. If you have strong friendships and still long for a partner, or work long hours to numb your feelings and then feel a wave of inadequacy hit you as soon as you sit down, then the problem still exists. It’s always up to you to decide whether your problem is adequately solved.

However, sometimes solutions have nothing to do with problems. If you’re acting out a pattern you learned in your abusive childhood, and you’re a happy functional member of society, that’s… fine? Who cares? If a situation in your life sucks, but you’ve figured out how to work around it and have a decent life anyway, then hooray! Victory!

It is particularly helpful to consider solutions unrelated to your problem if:

Your problem is impossible for you to fix: death, aging, idiopathic chronic illness, the fundamental personalities of your loved ones, the immensity of suffering in the universe, humanity’s imminent demise due to [insert favorite apocalypse here], Donald Trump.

You have put in a good-faith effort to fix your problem and it didn’t help.

It feels impossible to make any progress on your actual problem. You feel dread or overwhelm even thinking about it.

You have gotten by just fine without solving your problem in the past and think you can return to the status quo.

People Are Different

A common theme you might have noticed is that people are very different from each other.

People often propose one-size-fits-all solutions to problems. The secret to getting your baby to sleep through the night. The evidence-based, science-backed cure for depression. The exercise routine that will make anyone get their best body. The top twelve tips that will get YOU a harem of adoring and eager-to-please 10/10s.

But those solutions don’t work for everyone. People have different skills, personalities, and life advantages. People have different needs, limits, and constraints on what the situation can look like. And—even if two people seem to have the same problem—their goals can be completely different.

You can’t give the same baby sleep cure for a stay-at-home parent as for a working parent. For someone with infinite patience for soothing children to sleep as for someone who easily tolerates crying. For someone who needs eight hours of uninterrupted sleep as for someone who just needs the schedule to be predictable. For someone who is basically on top of things as for someone who is already underwater and sinking deeper every day. And sometimes you need to take a step back and go “maybe we don’t need to fix the baby’s sleep. Maybe your spouse needs to take the night wakeups instead.”

There is no one single cure for any complicated life problem. But there are a bunch of ways of thinking about problems that can help you figure out something that will work for you.4

Despite the name, solution-focused brief therapy was intended to be practiced by both therapists and many non-therapists, such as school guidance counselors or probation officers. Or life coaches.

Except maybe the ten million dollars, if you check your bank balance first thing every morning.

And if you want someone to listen to you and help talk you through it, I am taking life coaching clients!

This is really, really good. I think it's good generally, partially because it doesn't quite feel like therapy -- it seems to see specific problems which perhaps live in the world rather than in a person's head, broadly speaking. So the solutions often will involve acting in the world rather than adjusting one's mental patterns. And that's very useful and often ignored by "therapy industrial complex".

But what makes this text particularly good is its focus on the idea that "workarounds are actually solutions", and how and why, and that a workaround doesn't necessarily mean attitude/emotional adjustment, that it could be practical and still effective.

As someone who's stayed up late playing video games and is essentially a zombie despite it being a workday, I'd never claim to be a leading authority on doing life good.

But the problems in my life I've been able to overcome, the solution process has looked like this. This is really important and useful stuff, and anyone who's struggling should read it. I'll likely be sharing this with friends and family.

I'll also add the secret ingredient I needed - you don't need permission to pursue a solution you know will work for you. I'd spent 7 years and $200k getting a law degree, and the solution to my depression, anxiety, declining health, etc. was to *stop being a lawyer*. This was blindingly obvious to anyone who had even a passing familiarity with my situation. Nonetheless I went to therapy to try to solve my depression, anxiety, declining health, etc., and my therapist, thank goodness, was not running a scam to sell me more therapy. I had one session, he said "you don't need my permission to do the thing that will fix your problem, but if it helps you have it" and that was that.

The solution might not be standard. It might raise eyebrows. You might have to justify it to your friends and family. It might *cause other problems* you don't have a current solution for, and you just prefer those problems to this one. That's fine! As long as you're not hurting anyone (or these actions will cause you to hurt them less!) just do the thing that will obviously work. Why wouldn't you do the thing that will obviously work?