Effective Altruism: Quantitative Mindset

thinking with numbers

Disclaimer: For ease of writing, I say “effective altruism says this” or “effective altruists believe that.” In reality, effective altruism is a diverse movement, and many effective altruists believe different things. While I’m trying my best to describe the beliefs that are distinctive to the movement, no effective altruist (including me) believes everything I’m saying. While I do read widely within the effective altruism sphere, I have an inherently limited perspective on the movement, and may well be describing my own biases and the idiosyncratic traits of my own friends. I welcome corrections.

I.

I’ve heard it said that the two principles of rationality are:

Do the math.

Pay attention to the math.

This post is about the first one.

II.

When I was in high school, my best friend announced one day that she wasn’t eating microwave popcorn any more. She’d read an article that said that someone had developed lung problems after eating two bags of popcorn a day for ten years.

I was a young rationalist with charmingly naive ideas about winning people over through argument. So I pointed out to her that popcorn lung is very rare, that popcorn lung from eating microwave popcorn instead of working in a popcorn plant is even rarer, that the popcorn lung case was newsworthy specifically because it was so rare, and that if she wanted to improve her health through her diet she’d be far better served by eating more vegetables and fewer chocolate-chip cookies.

This is why I was not popular in high school.

People often behave irrationally because they don’t think mathematically. Like my high school best friend, they struggle with reasoning about how probable an event is. Often, people fail to multiply two numbers together, or divide one number by another number. And exponential growth gets almost everyone.

For example, consider lotteries. Most lotteries have about a 1 in 300 million chance that your ticket is the winning ticket. Americans spent $97.8 billion dollars on lottery tickets in 2022. For comparison, the same year we spent $7.4 billion—less than 10% of that amount—on going to the movie theater.

Buying a lottery ticket is stupid. Yes, it allows you to daydream about being rich. If you want to daydream about being rich, you can take a walk and look for spare lottery tickets that someone dropped on the ground—it doesn’t actually reduce your chance of winning the lottery by any appreciable amount.

People don’t buy lottery tickets as a form of structured daydreaming. People buy lottery tickets because they didn’t do the math—because to them 1 in 300 million is the same as 1 in 300 billion, or 1 in 300,000, or 1 in 3,000. It means there’s a chance, right?

Similar cases of failure to reason mathematically:

“I’m only spending $7 on a coffee and pastry every day. If I cut back on that, it wouldn’t do anything for my budget, not when rent costs $2000/month.”

“Sure, I could easily afford to buy a new dishwasher, but my jury-rigged solution only takes three minutes every time I do the dishes.”

“All those plane crashes! Flying is so dangerous these days. I’m going to drive to visit my relatives.”

“Here are all the precautions I take about serial killers.”

“I bought insurance on my concert ticket so I’ll get a refund if it turns out I can’t go.”

“Covid-19 isn’t a big problem, because there are only a few hundred cases in the United States.”

III.

People often fail to do the math about their own lives, but they really fail to do the math about doing good. You care a lot about paying your rent, so at some point it might occur to you to multiply $7 by 30 and observe that you’re spending 10% of your rent on your morning coffee. You have much less personal investment in the outcomes of your do-gooding. They benefit someone else, often someone you’ve never even met.

Indeed, people are often specifically opposed to applying quantitative reasoning to doing good. When you help others, it’s supposed to come from the heart. It’s supposed to be an authentic upswelling of emotion. You’re not supposed to be sitting there with your spreadsheets, calculating out exactly how much you can get for your dollar. Quantitative reasoning seems ungenerous, unempathetic, even cruel.

Now I’m going to walk through four examples of quantitative reasoning in effective altruism: one general one, and one for each of the three most popular effective altruist cause areas.

General effective altruism. In the classic study of scope insensitivity, people were divided into three groups and asked how much money they’d spend to rescue 2,000, 20,000, or 200,000 birds from drowning in oil ponds. The answers were, respectively, $80, $78, and $88. [ETA: a commenter notes that the original study got unusually similar results because it told people what percentage of the population the birds were, and the percentages looked similar; they pointed me towards further research that shows that people are somewhat more scope-sensitive than implied by that study, though still not perfectly scope-sensitive. I regret the error!]

People don’t think “how much would I pay to rescue one bird from a pond? I’ll multiply that by the number of birds rescued, and then I’ll know how much I’m willing to donate.” They think about how bad a drowning bird is, and then give an amount of money that matches how much the mental image upsets them.

As Paul Bloom wrote in Against Empathy:

To get a sense of the innumerate nature of our feelings, imagine reading that two hundred people just died in an earthquake in a remote country. How do you feel? Now imagine that you just discovered that the actual number of deaths was two thousand. Do you now feel ten times worse? Do you feel any worse?

In general, people don’t give more money to causes if more beings are helped. This alone is one of the major differences between effective altruist reasoning and everyone else’s reasoning.

Global poverty. According to Toby Ord’s The Moral Imperative For Cost-Effectiveness In Global Health,1 in global health, “moving money from the least effective intervention to the most effective would produce about 15,000 times the benefit, and even moving it from the median intervention to the most effective would produce about 60 times the benefit” (my bolding). Again, this is within the single cause of providing healthcare to the global poor. Certain causes, such as renovating the Lincoln Center to have better acoustics2 ($100 million), no doubt are many many more orders of magnitude less effective.

This is batshit. No one would ever make a decision that is fifteen thousand times worse than another decision if their own interests were involved, no matter how averse they are to arithmetic. But if your decisions affect someone else, it’s easy to reason with your heart rather than your head. You’re not the one who faces the consequences.

Animal advocacy. Animal Charity Evaluators has one of the finest pieces of data visualization in the effective animal advocacy movement:3

Farmed animals vastly outnumber pets in need of shelters, and yet pets are far more likely to receive donations than farmed animals. This chart actually makes the farmed-animal situation look better than it is. More than a quarter of farmed-animal welfare funding comes from a single effective-altruism-affiliated donor, Open Philanthropy.4 Before effective altruism, the difference was far starker.

Sometimes animal advocates ask why effective animal advocates focus on farmed animals to the exclusion of lab animals and shelter animals. All three kinds of animals matter, after all. Other animal advocacy organizations like PETA work on all three. The answer is that we compared the size of two numbers.

Existential risk. I once had a conversation with one of my friends that went something like this:

Friend: I feel a lot more uncertain about AI than most people we know do. I think maybe 50% chance of AGI by 2050?

Me: [nodding along]

Friend: —which is why AI is one of my top cause areas, because being more uncertain about something doesn’t make it safer.

As I wrote in The Four Guys Who Wouldn’t Shut Up And Were Wrong About Everything:

Their favorite mantra was “the science is not settled.” We aren’t sure whether tobacco smoking causes cancer—or whether air pollution is the reason that some samples of rain water are as acidic as lemon juice—or whether climate change is caused by something else, like sunspots. Therefore, we shouldn’t do anything about the situation until we know for sure that something is going wrong…

However, we should often take action about problems we’re uncertain about. Those Four Guys reliably assumed that the cost/benefit analysis was always in favor of the status quo—even when it wasn’t. It’s not that costly to society to regulate the pollutants that cause acid rain, and once you do you’ll quickly find out if your theory of acid rain is accurate.

We don’t want to find out how bad nuclear winter is by causing mass famines, or whether acid rain kills fish by driving irreplaceable fish species extinct. Many decisions we make, like putting carbon into the atmosphere, are irreversible. If you are unsure of the effects of your decision, don’t do irreversible things because that’s what you’re already doing. Sometimes, we need to make decisions based on weak or preliminary evidence, because that is the evidence we have available, and the other alternative is catastrophic.

If you think there is a 10% chance of artificial general intelligence in the next ten years,5 and a 20% chance that artificial general intelligence will drive us extinct, that’s a 2% chance of humans going extinct. Some people look at those numbers and go “wow, only a 2% chance, that’s not going to happen, nothing to worry about.” Other people look at those numbers and go “holy shit, that’s one of the most important problems in the world.”

The latter sort of person becomes an effective altruist.

IV.

The well-kept secret about cost-effective analyses is that they’re all fake.

Deworming charities give children pills that cure parasitic worm infections. A long-term randomized controlled trial showed that people dewormed as children have ~10% higher income as adults. However, this is only a single study, and epidemiologists have raised numerous critiques of its methodology (the so-called “Worm Wars”).6 Some people characterize this situation as “deworming might not work,” which I hate. Deworming definitely works. If you take deworming pills, you will no longer be infected with parasitic worms. The dispute is about how bad it is to be infected with parasitic worms.

GiveWell’s cost-benefit analyses adjust the effect of deworming charities down by 87% to account for this dispute. Why 87%? Well, you can go read their explanation of how they came to that number, but I hope they won’t take it as an insult to their excellent organization if I say that they kind of pulled it out of their butts. A very rigorous and statistical butt-pull, to be sure! But ultimately you can’t put a concrete number on “how likely is it that this study is fake?” in the same way you can put one on “how many pills do we give out per dollar?”

GiveWell’s 2023 cost-effectiveness spreadsheet says that Deworm the World is 34.4 times as good as an equivalently sized cash transfer in Kenya, but only 8.9 times in Lagos. This is, in an important sense, made up. We don’t know that Deworm the World is precisely 34.4 times better than cash transfers in Kenya. It could be 30 times, or 36 times, or even 34.5 times.

Why, then, do a cost-benefit analysis at all?

Because if you sit down, and make your spreadsheets, and do your fancy rigorous statistical butt-pulling, what you can say is: “deworming is cheap. Deworming is so cheap that, even with the most conservative assumptions we can reasonably justify, even if you assume that in seven out of eight universes it has no long-term effects at all, it is worth doing. Deworming is so fucking cheap.”

If you don’t think with numbers, all you have is two facts. Deworming probably doesn’t have significant long-run effects. Deworming programs are very inexpensive. Does one fact outweigh the other? Who knows? Not me.

Deworming is relatively uncertain for a global public health intervention, but we still know a lot about it. But in more speculative areas like animal advocacy or AI safety, quantitative thinking is even more important. Even if your numbers are kind of made up, thinking with numbers allows you to answer questions like:

Is this intervention so overwhelmingly good that I should do it, even given how uncertain I am?

What downsides of this intervention do I predict? How likely do I think they are compared to the advantages?

What assumptions am I making? Do I really believe them?

Of the things I’m uncertain about, which have the biggest effect on the answer? How can I get more information about them?

For more on practical cost-benefit analyses, I highly recommend this post.

V.

When I was first brainstorming this series with friends, I think probably the most common suggestion I got was about this point.

“People keep thinking that I think with numbers because I don’t care,” they said. “But I think with numbers because I do care. Numbers are how I care.”

Effective altruism can seem cold and calculating. But to an effective altruist, quantitative reasoning comes from profound compassion. People are dying of treatable illnesses. Children grow up unable to read or do math. Citizens have no say in their governance. Animals are being tortured. The world is warming, and it teeters on the brink of destruction half a dozen different ways. We care, and because we care we want to stretch every dollar as far as we can. And so we want to apply to saving a world a hundredth of the amount of cleverness and skill that our society does to the correct pricing of call options on Eurodollar futures.

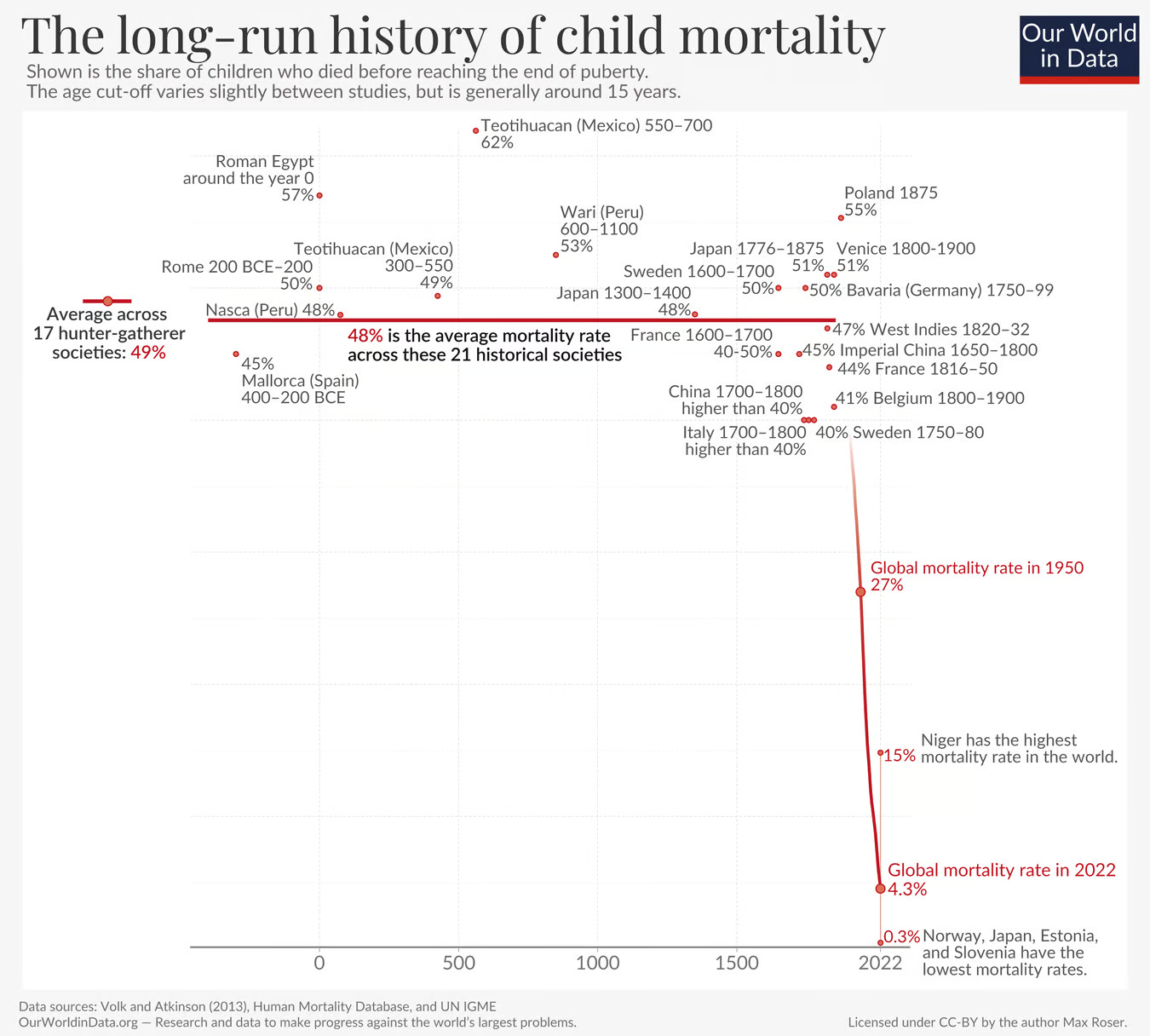

As Bertrand Russell probably didn’t say, “The mark of a civilized man is the capacity to read a column of numbers and weep.” I am too uncivilized for number columns myself, but I have been driven to tears by any number of charts.

So here is the second of my three core claims of effective altruism: think with numbers.

Have I cited this paper often enough on this blog? Probably not.

I have also cited this one before but I figure that David Geffen needs to experience more public shaming.

I have my quibbles with “animals killed” as a metric because I’m not sure if I think animal death is bad in and of itself, but eh you get the idea.

The farmed animal welfare movement spends about $200 million a year; I eyeballed about $50 million of grants a year using Open Philanthropy’s grants database.

Of course, many people who work on AI safety think AI is far more likely than that.

You can find out Much More Than You Wanted To Know about deworming by following the links on GiveWell’s pages about it.

An alternative explanation of your bird example: people care about species rather than individuals. Even species is generic. Do they differentiate between barn owls and great horned owls? I doubt it. Do they differentiate between my dog and an undifferentiated dog? Probably. But I don't think they put "number of injured birds" in the same category as "number of injured neighbors".

I disagree with this, because you're ignoring differences in values. You can't do the math to tell you what values you should have.

> Certain causes, such as renovating the Lincoln Center to have better acoustics ($100 million), no doubt are many many more orders of magnitude less effective.

This is a little silly. Less effective... at what? Less effective at saving lives, sure, but that wasn't the intended purpose of the money. Saving lives isn't the only goal or only thing that matters. You might as well say the deworming donations are less effective because they are less effective at improving acoustics, promoting art, or stopping global warming.

This is about values, ultimately, and everyone is going to have different values. I doubt Geffen wanted to donate to do the most good or save the most lives - that's simply not what philanthrophy is about most of the time. He wanted other things he valued, like honor and recognition, and he presumably wanted to support an organization and cause that he personally cared about. There's no amount of doing the math that can possibly tell you what values you should have.

> Farmed animals vastly outnumber pets in need of shelters, and yet pets are far more likely to receive donations than farmed animals.

Well, yes, because people care a lot more about pets than they do about farm animals. This isn't something you can "do the math" on and get the correct answer about which animals you should value more than others.

I made a comment about this in a previous post, but I just find that Vox article extremely disturbing...

> "It’s useful to imagine walking down Main Street, stopping at each table at the diner Lou’s, shaking hands with as many people as you can, and telling them, 'I think you need to die to make a cathedral pretty.' "

> "If I were to file effective altruism down to its more core, elemental truth, it’s this: 'We should let children die to rebuild a cathedral' is not a principle anyone should be willing to accept. Every reasonable person should reject it."

Well, no, that has nothing to do with effective altruism whatsoever. There's no way you can "do the math" to determine how much you should value art and culture.

If you decide you care about saving lives to the exclusion of all else, then sure, you can do the math for the most effective way to save lives. But that's just not the only thing people care about.

Most of the donations to rebuild the cathedral were unlikely to go towards saving dying kids. People donated to that specific cause because they cared about it.

The problem with that quote is that there are always dying kids, so if you see any money spent on anything as "letting children die" you're left with the conclusion that no money should ever be spent on art, or anything else that doesn't directly facilitate lifesaving. That can't be correct.

I personally value art a lot more than saving strangers' lives. It's just a difference in values, and it's bizarre to me that that author thinks every reasonable person should not value art enough to spend money on it.

There was some LW post that quoted Hume on this topic, saying something like "reason should serve the passions." You have to figure out what you value first, and then try to do it effectively. And not everyone values saving lives over everything else.