The Effective Altruist View of Politics

Disclaimer: For ease of writing, I say “effective altruism says this” or “effective altruists believe that.” In reality, effective altruism is a diverse movement, and many effective altruists believe different things. While I’m trying my best to describe the beliefs that are distinctive to the movement, no effective altruist (including me) believes everything I’m saying. While I do read widely within the effective altruism sphere, I have an inherently limited perspective on the movement, and may well be describing my own biases and the idiosyncratic traits of my own friends. I welcome corrections.

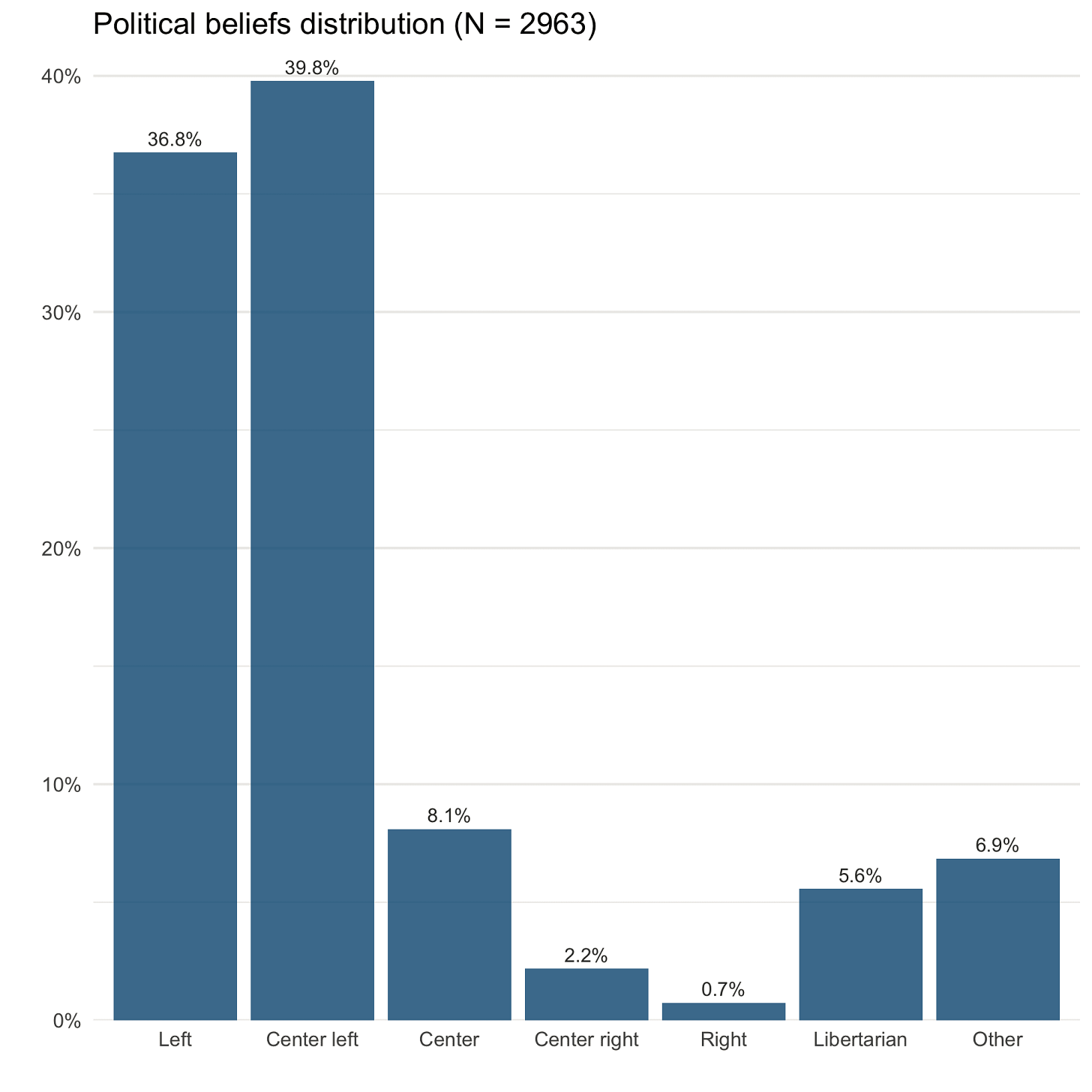

A not entirely inaccurate gloss on the effective altruist approach to politics is that it’s absurdly progressive:

But I think the overwhelmingly left and center-left nature of effective altruism hides a number of ways that effective altruists differ from many (but not all) people on the left.

Liberalism

Effective altruists are liberals in the political philosophy sense. “Liberalism” is a loose term that refers to a wide variety of beliefs, many of which disagree with each other. Common themes in liberal political thought include:

Economic freedom (markets, private property).

Political freedom (civil liberties, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, bodily autonomy, privacy).

Rule of law (equality under the law, clear and consistently applied legal rules).

Consent of the governed (democracy).

Liberalism is the dominant political ideology in the developed world, so much so that even quite illiberal viewpoints feel the need to justify themselves with liberal premises. But I think effective altruists are still quite distinctively liberal.

Most people absorb some vague, unexamined liberal beliefs from the broader culture. They drift back and forth between liberalism and illiberalism based on what is presently convenient. They don’t tend to be principled about their liberalism, because having principles requires thinking about political philosophy more than most people do.

Conversely, effective altruists tend to explicitly understand themselves as liberals (whether or not they know the term). As such, their liberalism tends to be more consistent and coherent. Effective altruists are more likely to have a rigorously thought-out stance about bodily autonomy or civil liberties, or at least to think that they ought to have one. They are more likely to have their political beliefs meaningfully constrained by their liberalism: “that guy is evil, but if he’s not guilty beyond a reasonable doubt he shouldn’t be in prison”; “that religious practice is an atrocity, but we should tolerate it.”

Effective altruists also care more about their liberalism than most people do, in part because of their historical and global perspective. To most people in the Anglosphere, kings are an obsolete yet harmless and charming institution, like black tie dress codes or private boarding schools that teach Latin. Effective altruists try to think about history like it actually happened to them; for most of history and in much of the world today, any freedom ordinary people had was due to the mercy of the violent bandits who could rob them with impunity. Most people in the Anglosphere take liberal democracy for granted.1 To effective altruists, liberal democracy is a rare and precious thing which must be zealously maintained.

Economics

In his Principles of Economics—the world’s most popular economics textbook—Gregory Mankiw summarizes economics as consisting of ten principles:

People Face Tradeoffs.

That is, to get something you want, you normally have to give up something else you also want. You can spend money on ice cream or a book; you can spend an hour napping or talking to a friend. You can’t do both.

Societies also face tradeoffs: spending on national defense versus welfare; a clean environment versus more abundant consumer goods; high taxes versus low spending.

The Cost of Something Is What You Give Up To Get It.

The cost of something isn’t just money. For example, if you go to college, you can’t spend that time working a job or pursuing your dream of becoming a ballerina. (This is called “opportunity cost.”)

Rational People Think At The Margins.

I explained this one in the neglectedness section of this post.

To make good decisions, you need to think, not about the average value of your actions, but about the marginal value of the decision you actually face. For example, if you’re exhausted, don’t think about the average benefit of studying for finals; think about the marginal benefit of the next 15 minutes of studying. If you’re deciding whether to raise taxes, don’t think about the average benefit of government spending; think about whatever program the taxes would fund that they otherwise wouldn’t fund.

People Respond To Incentives.

People do more of things they’re rewarded for and less of things they’re punished for. If a job is pleasant or has a high salary, people are more likely to work it. Conversely, if a job has long hours or mean coworkers, people are more likely to quit.

Trade Can Make Everyone Better Off.

Everyone is better off if some people specialize in teaching and others in sewing and others in farming, instead of every family harvesting its own wheat and sewing its own clothes and teaching its own children.

Everyone is better off if some countries specialize in iPhone manufacturing and others in bananas and others in finance, instead of each country producing its own iPhones and bananas and exotic stock derivatives.

Markets Are Usually a Good Way to Organize Economic Activity.

The “invisible hand” causes people, acting in their own self-interest, to make everyone better off.

Markets are better than central planners at combining individuals’ local information (like what goods they want and what jobs they want to work).

Governments Can Sometimes Improve Market Outcomes.

For example, governments are needed to enforce laws; to protect bystanders from the side effects of decisions they aren’t involved in; and to make people have a more equal share of society’s resources.

A Country’s Standard of Living Depends on Its Ability to Produce Goods and Services.

Richer countries are countries where an hour of work produces more valuable goods and services.

The other two principles are Prices Rise When The Government Prints Too Much Money and Society Faces a Short-Run Tradeoff between Inflation and Unemployment, but I haven’t seen either of those come up much in effective altruist thought so I shall not linger on them.

In general, effective altruists accept the first eight of Mankiw’s principles of economics. They consider them to be fundamental to creating a just and happy society. See the connection here to liberalism: economics provides a justification for caring deeply about free markets, minimally restricted trade, property rights, and so on.

Effective altruists also tend to like “the kinds of policies economists like.” I can’t sum these up into single principles, but they include policies like:

Carbon taxes, instead of anti-fracking activism, bans on gasoline cars, or subsidies for solar.

Congestion pricing.

More broadly: taxes on behavior we’d prefer people not engage in (such as pollution), instead of banning them.

Reducing housing prices through upzoning, urban development, and increasing the housing supply, instead of public housing or requiring housing to be affordable.

Cash welfare, instead of in-kind welfare or programs that limit what people can spend money on.

Free trade instead of tariffs.

Conversely, effective altruists tend to be less likely to get their political ideas from other forms of social science, such as political science, international relations, sociology or anthropology.

Positive-Sum

Probably the most important concept to understand the effective altruist approach to politics is conflict vs. mistake theory.

In conflict theory, politics is a war: between Democrats and Republicans, between gays and homophobes, between elites and populists, between the rich and the proletariat. People are opposed to each other because they actually want different things, desires which are fundamentally incompatible. Conversely, in mistake theory, politics is a set of empirical disagreements. Everyone wants the same things: wealth, health, freedom, equality, a complete end to Disney live-action remakes. But some people think that Medicare For All will make people healthiest, while other people think that a free market in healthcare would work best.

Obviously, both conflict theory and mistake theory are true sometimes. Libertarians and Bernie Bros both want people to live long, healthy lives and simply disagree about what health care system would bring this about. At the same time, like, I want to make out with lots of hot girls, and social conservatives aren’t out here going “I’m opposed to gay marriage because I’m worried marriage will cramp Ozy’s style and keep them from the heights of girlkissing otherwise available.”

If you attempt to pin down most effective altruists on the topic, they will agree with me here. But I think it’s difficult to understand the effective altruist approach to politics unless you realize that, on some preconscious level, most effective altruists think of conflict theory as the bad one. Conflict theory means you’re strawmanning people you disagree with, that you don’t believe in cooperation and coordination, that you hate the outgroup and are biased in favor of the ingroup—three of the worst sins in effective altruist thought.

So this means that effective altruists typically assume that:

Every problem has a solution that leaves people better off on average.

Politics shouldn’t have winners and losers; ideally, everyone should be happy with the outcome.

If you disagree with someone about policy, it’s because you believe different things about the world, not because you value different things.

If you convince someone to have more accurate views about the world, they’ll agree with you about policy.

All political sides have a grain of truth in them; we make progress by synthesizing those grains of truth.

It’s a good idea to be “centrist” or “moderate.”

This consensus has been, uh, slightly battered by the Trump years, but I still think it holds a lot of sway.

Technocratic

Some people accuse effective altruists of not being interested in politics. I don’t think that’s true: for example, 80,000 Hours’s top-ranked career path is AI policy and governance, and Effective Altruism DC is large and thriving. But effective altruists do have a particular approach to politics. They join the civil service and devote themselves to optimizing something no one else is paying attention to, or they join think tanks and write papers for an audience of six people every one of whom holds the fate of millions in their hands.

On the other hand, effective altruists are uninterested in mass mobilization: activism, awareness raising, putting pressure on politicians, running for political office. In part, this is because effective altruists aren’t very good at it. Effective altruists are notoriously awful at making signs for protests: all their signs are fifty words long because of all the caveats and statistics and citations.

And the less said about effective altruists’ one attempt at electoral politics the better.

Effective altruists deeply value the truth, and mass mobilization—for better or for worse—involves compromising on the truth in the way effective altruists mean it. Catchy slogans cut out nuance, leave out tradeoffs, and often misrepresent the views of people you disagree with. Raymond Arnold has said that if you coordinate with thousands of people your message gets to be five words long; I think that’s a bit of an exaggeration, but it points to something real. Effective altruists cringe away from the idea of simplifying their messages for a broad audience. It feels like lying.

Since most people don’t agree with economists, you often specifically need to present your economically informed views in a way that makes sense to people who believe in (say) the lump of labor fallacy. Effective altruists really hate that.

Effective altruists also have a distaste for partisan politics, probably related to their distaste for conflict theory. Mass mobilization asks the same question as Mac from It’s Always Sunny In Pennsylvania: “but who versus? Who are we doing it versus?” Effective altruists, conversely, often want to follow Robin Hanson’s advice to pull the rope sideways: to avoid polarized tugs-of-war between the right and the left by primarily advocating for policies (often very wonky) that no one cares about.

Less nicely, effective altruists have a bit of an elitist streak. For example, 80,000 Hours’s career advice only intermittently acknowledges the existence of people who attended college outside the Ivy League or Oxbridge—much less people who didn’t go to college at all. This decision is defensible—powerful people in fact have more ability to influence the world, that’s what power is—but it does reflect a broader trend in effective altruist culture. Effective altruists feel comfortable with think tanks and the civil service because they involve educated, upper-middle-class or upper-class people socializing with each other and making important decisions. They feel less comfortable with forms of activism that require reaching out to poorer, less educated, and lower-class people.

Incrementalist

In general, effective altruists tend to prefer policies shaped like “slashing minimum lot sizes in cities will decrease home prices and reduce displacement” and to dislike policies shaped like “ending capitalism.” Effective altruists tend to prefer smaller changes that, if they change the broader structure of society, do so gradually and reversibly.2

In part, this is because effective altruists tend technocratic. “Slashing minimum lot sizes” is a wonky, technical policy you can put into practice without consulting normal people; “ending capitalism” requires everyone’s buy-in. In part, this is because effective altruists think the world is improving and don’t want to risk a radical change that might kill the goose that lays the golden eggs. In part, effective altruists are worried that big, structural changes might be bad, and want to implement policies it is possible to reverse.

The exception to this rule, of course, is artificial intelligence, which is an extraordinarily rapid change. But effective altruists often warn against artificial intelligence specifically because the change might be so swift and all-encompassing: we might not be able to go back and change our AI policies if they turn out to be misguided. And effective altruist AI policy recommendations are often3 remarkably incrementalist: for example, the post I linked proposes that AI is one of the most important problems facing humanity, and then recommends policies like “educate decision-makers about AI,” “let digital minds express the desire to leave their current circumstances,” and “make a treaty about how to divide up extrasolar resources.” These are really quite wonky! Further, effective altruists commonly believe we should slow down AI development, so that the changes are slower and easier to reverse.

I don’t want to overstate how politically weird effective altruists are. To a large extent, effective altruists have the ordinary views of a center-left, politically involved person in the Anglosphere. Very little of this would be out of place in, say, the comment section of Slow Boring. Given how weird effective altruists are about the rest of their worldview, perhaps the most interesting part of their political beliefs is how normal they are.

Maybe less so today.

Beta readers pointed out one exception, which was the high level of support among effective altruists for covid lockdowns. Perhaps related to Bayesianism, effective altruists are fairly willing to make a best guess when they have limited information but the situation is very time-sensitive. Other institutions that are equally incrementalist will tend to wait until the evidence comes in.

Policies recommended by Eliezer Yudkowsky specifically tend to be less reformist: Yudkowsky is more radical than most effective altruists.

I think of myself as an EA (or at least EA-ish), and I don't really agree with these points:

* Every problem has a solution that leaves people better off on average.

* Politics shouldn’t have winners and losers; ideally, everyone should be happy with the outcome.

I wish this were the case, but I think realistically, most solutions will leave some people worse off somehow..

For example, I think we need to entirely eliminate human use of animals. This will clearly eliminate a bunch of existing jobs (factory farm worker). What we can do to ameliorate that would be to compensate them with cash payments. But some of those people will still be unhappy, because they derived a sense of self or satisfaction from the work, and will think they are worse off, even with the compensation.

So I think we can find solutions that have as few economic "losers" as possible, and compensate them financially, but we probably can't fix the _emotional_ pain that people feel because of a policy change.

* If you disagree with someone about policy, it’s because you believe different things about the world, not because you value different things.

I also disagree with this. It's quite clear that people have values beyond the very basic shared values like being healthy, having enough food to eat, shelter, etc. For example, lots of writing about conservatives has talked about conservatives value tradition, authority, and sanctity/purity more than liberals.

Given that difference, it seems like there's no policy that will satisfy everyone.

#5 "Trade Can Make Everyone Better Off." is false. The truth is that total gains are larger than total losses, but some people -- the guy who was a well liked foreman at the local factory but is too old to retrain for a new career -- end up worse off.